This is a moment in which the old order is showing serious signs of decay. The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed what the poor have known for a long time – that our current economic and political systems have been set up to benefit a shrinking few at the expense of the rest of us. Our health, our wellbeing, and the very lives of our loved ones are being sacrificed on the altar of big capital in the desperate hopes of preserving a system in its death throes.

How can we make sense of this moment as we live through it? What are the dangers and opportunities presenting themselves? How can we be ready, as the song says, for change to come? This third issue of the University of the Poor Journal brings together perspectives from a diversity of angles and experiences, current and historical, that aim to help us understand and take advantage of this moment to build the movement.

History provides us with important lessons for today as we build the unity and power of the poor against the dictatorship of the rich. The political report included in this issue goes into more depth regarding several key moments in U.S. history. For the purpose of this introduction, we will focus on the Civil War and Reconstruction. In our study and discussion of W.E.B. Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction in America, we have tried to recognize and celebrate the accomplishments of the dispossessed – first and foremost, the end of chattel slavery – as well as take a hard look at where efforts for revolutionary change fell short or were turned back.

The Civil War was a time in which enslaved Black workers, the social force with the least to lose in maintaining the order of the society at the time, radically changed what was politically possible and became the decisive factor in the Union victory and in their own emancipation. Du Bois calls this mass movement “the General Strike.” Early in the war, thousands upon thousands of enslaved Black workers began to refuse the terms of their enslavement, stopping work and “stealing away” toward Union camps in the mid-South. Neither Northern nor Southern political strategists expected this, and it threw off their entire strategic calculus.

At first, Union generals rejected the claims of freedom and assistance offered by the self-liberated Black workers, and some even tried to return them to their masters. Only in radical abolitionist circles was emancipation without compensation being discussed, and it wasn’t a reason the North went to war.

Yet as the war dragged on, Lincoln was obligated to make emancipation part of his promise. As the North sustained losses and had difficulty recruiting new soldiers, the president needed the half million Black workers and the 300,000 Southern poor whites who had sworn allegiance to the North against the Slave Power. The General Strike is one powerful example of how the rejected of society, acting together, fundamentally changed the outcome of a ruling-class conflict toward true democracy and freedom.

A kernel of democracy was born in the South as the oligarchy of the Southern planters was defeated. Approximately $4 billion in slave owners’ human property, the dominant form of capital in the U.S. at the time, was reappropriated by Black people themselves. This leading social force, however, couldn’t sustain revolutionary change on its own. For Reconstruction to be viable, abolition democracy needed Northern capital, in alliance with which it had built the insurgent Republican Party to break the political dominance of the Slave Power. Now, to break the continued intransigence of the Southern planter class, Wall Street was quick to temporarily align with liberated Black people and their allies in the South to subjugate the former slave owners.

Du Bois notes that while their level of ascendancy was uneven throughout states across the U.S. South during Reconstruction, Black labor “exercised a considerable dictatorship over the state governments of South Carolina, Mississippi and Louisiana” (p. 487). However, Black labor, the abolitionists, and multiracial Reconstruction governments throughout the South didn’t have sufficient spaces to compare notes or strategize together, and therefore each was left isolated and only seeing part of a complex reality. That left these radical social reformers vulnerable to manipulation and unable to maintain political independence or a separate strategy from Northern capitalists.

“As the Negro laborers organized separately,” Du Bois writes, “there came slowly to realization the fact that here was not only separate organization but a separation in leading ideas, because among Negroes, and particularly in the South, there was being put into force one of the most extraordinary experiments of Marxism that the world, before the Russian revolution, had seen. That is, backed by the military power of the United States, a dictatorship of labor was to be attempted and those who were leading the Negro race in this vast experiment were emphasizing the necessity of the political power and organization backed by protective military power” (p. 358).

Du Bois notes that “the orbits of two widely and utterly dissimilar economic systems” that had coincided for a brief moment separated again. Wall Street found an easier ally in a brutal, racist Jim Crow regime which would discipline Black and white labor in the South, and by extension, the rest of the nation and world. The revolutionary moment was missed, and the dictatorship of the rich that was firmly established through the defeat of Reconstruction is one we still face today.

In the University of the Poor we sum up Du Bois’ analysis of the defeat of Reconstruction by saying, “Wall Street controlled the South, and the South controlled the nation.” Du Bois notes, “The party of Northern industry watched the beginnings of democratic government in the South with distrust. They did not expect Negro suffrage to succeed, but they did expect that it would soon compel the Southern oligarchy to capitulate to the dictatorship of industry. Their hopes were fulfilled in 1876” (p. 369-370).

Studying the significant accomplishments and final defeat of Reconstruction can deepen our commitment to the unity and leadership of the poor today. The fertile revolutionary moment that Reconstruction represented has much to teach us about assessing the alignment of forces and contradictory interests of our time, as well as relations of production and opportunities for new political formations that arise in moments of crisis. Despite the fact that ultimately, the full revolutionary potential of the moment was missed, this history shows the power of a multiracial, nonviolent army of the poor not only claiming a seat at the table, but leading the nation toward democracy and dignity for all.

We take strength in wielding history as we fight and lead in all kinds of poor and dispossessed communities, on all kinds of issues, and work to bring these struggles together.

The political report highlights the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival for its breakthroughs in three areas that are necessary for any effort toward fundamental change in the United States: the Bible, the Ballot, and the South.

Regarding the Bible, this issue of the University of the Poor Journal features an interview with Colleen Wessel McCoy on the Freedom Church of the Poor and the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign and Daniel Jones’s analysis of the struggle against exploitation and dispossession that led to the rise of the Jewish tradition.

Regarding the South, Ben Wilkins speaks about political unionism and the story of Raise Up the South, and Kymberly Smith and Lindsey Jordan share reflections about making the struggle a school while organizing in the region.

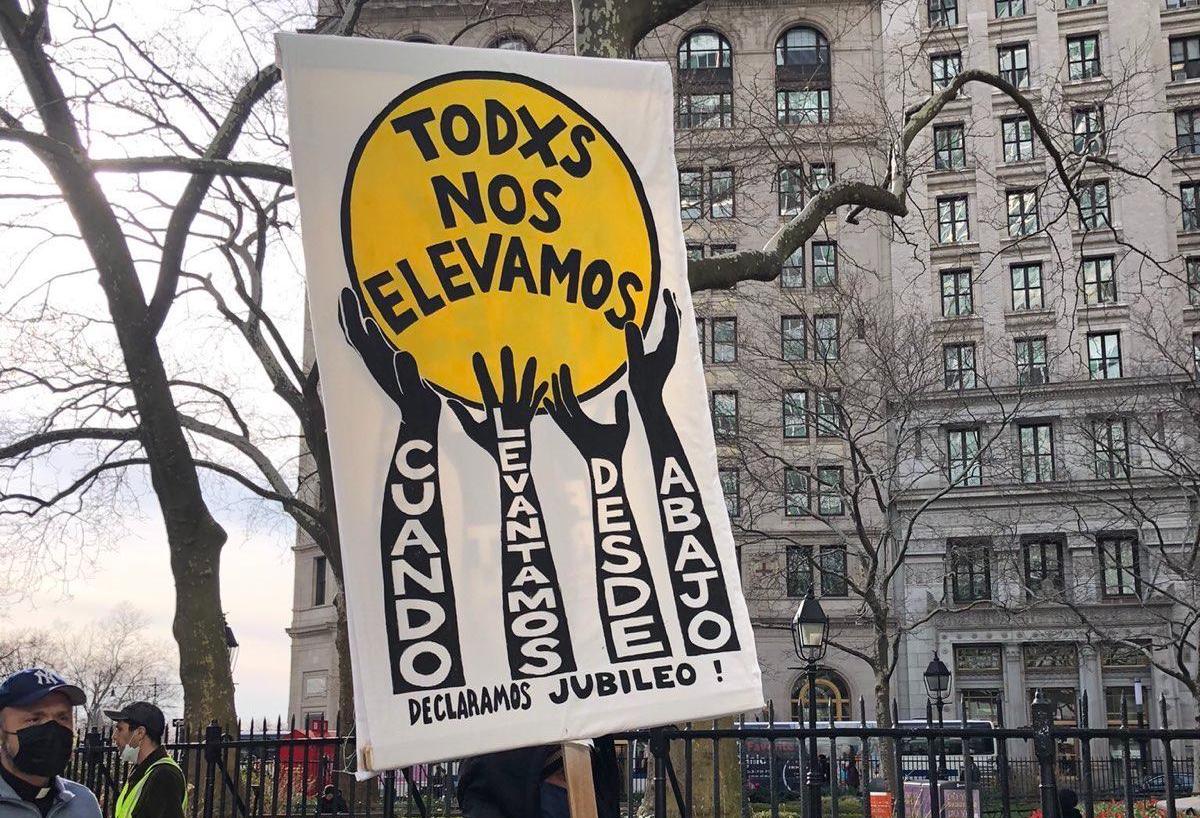

Another strategically important aspect of the work to unite the poor and dispossessed is unity across language, argue Emiliano Vera and Natalia Fajardo in their article about multilingual organizing in English and Spanish.

In addition, this issue features an interview with Olga Bautista about the fight against industrial pollution in Chicago. We’re also publishing John F. Keller’s explanation of historical materialism as a tool for studying US history and our own moment. And Bruce E. Parry has reviewed Principles for Dealing with The Changing World Order, a book by leading capitalist hedge fund manager Ray Dalio.

As we draw closer to the historic Poor People’s and Low-Wage Workers’ Assembly and Moral March on Washington and to the Polls on June 18, 2022, may we ground ourselves in the lessons of history and in the struggles of today, as arm and arm we march, pray, sing, and organize our way toward a world in which everybody has a right to live.

Tim W. Shenk, for the University of the Poor Journal Editorial Committee, in conversation with John Wessel-McCoy, Ciara Taylor, Anakaren Alcocer, Avery Book, and Phil Wider, coordination team for the Black Reconstruction in America study group, a project of the University of the Poor History & Political Strategy curriculum team.