by Emiliano Vera & Natalia Fajardo

The most visible aspect used to divide the poor and dispossessed is race. An interconnected dimension of humanity which has traditionally served as a tool of exclusion and discrimination, but which leaders of the University of the Poor are beginning to forge for inclusion, liberation and unity, is language.

Our stated mission at the University of the Poor is to unite and develop leaders across lines of division as we build a broad movement to end poverty. To that end, the Unity Across Language (UAL) committee was established in 2020, first to bring the voice of Spanish-speaking movement leaders to our educational spaces. UAL has grown into a body that spearheads the effort to center the strategic role language plays in our movement, in all of its expressions.

Multilingualism as an Element of Class Struggle

Making our spaces multilingual is an important step, but in itself, it’s not enough. The ruling class is well aware of the political significance of language. Philosophically, the issue of language is not just a matter of access or even “language justice.” Unity Across Language is one important way we carry out our strategy. Providing multilingual spaces should not be understood as an act of charity conceded by majority language speakers to minority language speakers. Rather, a commitment to clarity and competence in unity across language is vital to our success in uniting the different sections of the poor and dispossessed in the United States and across the globe.

It is in the best interest of our whole class, including poor white and monolingual people, to turn language from a barrier and a tool of separation, into a weapon for unity and liberation.

The work of Unity Across Language is not for multilingual or minority language speakers or immigrants to figure out alone. It is the responsibility of organizations and campaigns of the poor and dispossessed to learn from and build power with each other. Only through building Unity Across Language can we have access to the depth and breadth of people’s struggles around the country and world. If we don’t have that perspective, we’re at risk of fighting against each other.

In the U.S, our recent political organizing has been based on silos. We tend to compartmentalize by issue, identity or language. While it is important to have spaces where people express themselves in the language of their choice, we must learn the reality of, and organize with, the poor who speak another tongue.

For instance, English-speaking poor people are often left vulnerable to predatory, immigrant-blaming propaganda. In other circles, narrowly focusing on issues of immigration status and culture can make it so activists ultimately ignore fundamental issues of power and economic structure.

Historical Precedent for and Necessity of Unity Across Language

Unity Across Language forms an integral but often overlooked part of the history of the revolutionary struggles of the poor and dispossessed.

Across the Americas, Africa, Asia and Australia, confederations of indigenous peoples were most successful in resisting colonial expansion when they were able to unite across their great diversity of languages, while colonizers simultaneously provoked divisions using language as a wedge to inflame historical tensions. For example, the Seminoles united indigenous people and escaped slaves in Florida to resist American wars of conquest for decades. Haiti’s successful revolution was achieved by mobilizing enslaved people brought to Haiti from across Africa who spoke dozens of languages.

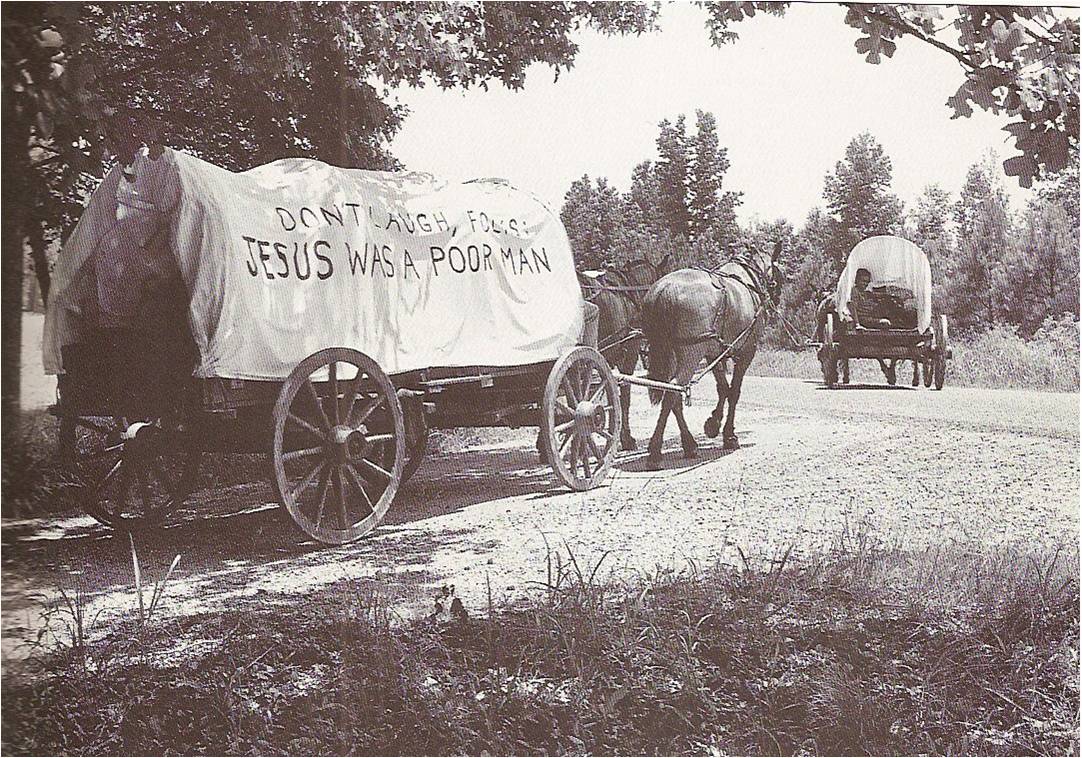

As capitalism developed, the U.S. took in millions of European peasants fleeing oppression only to turn them into the immiserated industrial proletariat. The labor movement made breakthroughs by organizing among immigrant workers, rallying speakers of Italian, Russian, Yiddish, German, Polish, Hungarian, and dozens of other languages, establishing multilingual parties and unions to represent them.

Meanwhile, the despotic Russian Empire that was called the Prisonhouse of Nations was overthrown by a working class unified across their many languages against the oppression of the czar. The multinational, multilingual Union of Soviet Socialist Republics that emerged would prove its commitment to internationalism and unity across language, for example, in the Baku Conference of the Peoples of the East, gathering leaders from across the colonized countries Asia and Africa. With the resurgence of nationalism during the collapse of the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia, we see once again that the stoking of linguistic division served international capitalism.

How we are Building Unity Across Language

We apply this philosophy and history to our on-the-ground organizing. For example, in Vecinos Unidos, based in Milwaukee, we remind participants that our multilingual spaces (and the logistical interpretation and translation to make them happen) is strategic and not just “to be nice or inclusive.”

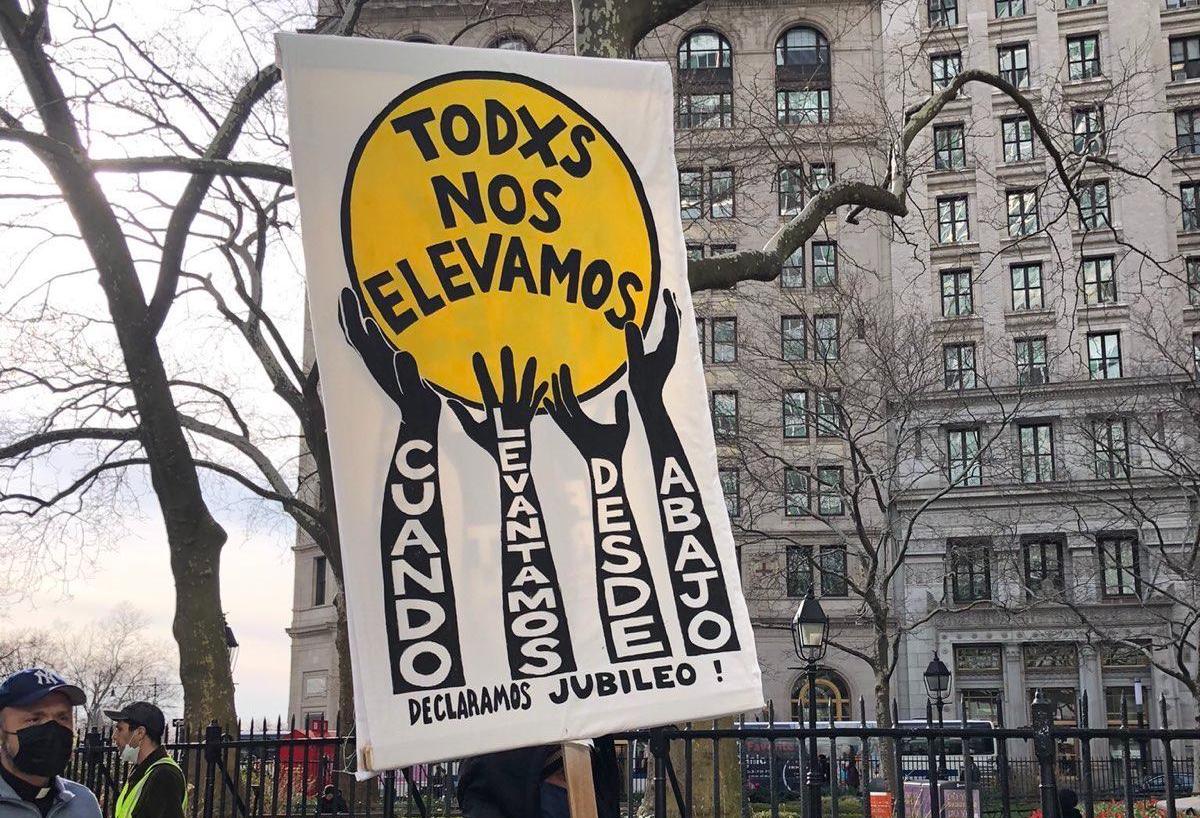

The broadest current expression in the U.S. of the effort to unite the working class is the Poor People’s Campaign, a space that challenges the nation to face the immorality and the irrationality of our economic system. Like the UPoor, this Campaign also builds unity across language by creating multilingual, multi-racial, cross-issue spaces for poor and low-income leaders to tell our stories, march together, and build our collective power.

The Poor People’s Campaign is gearing up for June 18th’s Moral March and Assembly in Washington D.C – coordinating at the state level to share experiences, create a vision, and bring strategic multilingualism to this event. Leaders from across the country are offering preparation events in Spanish, recording and teaching songs born in Spanish for all to learn. This last element is particularly relevant to the Campaign, where music plays a significant role in grounding us, projecting our message, and building unity beyond words. That is, rhythm, cadence and harmony all play their part in getting us “into step.”

This effort to unite across languages across this country (and the continent) will take an important step in forming our collective leadership and developing our clarity when we evolve from translating articles, into creating content born in other languages, so the wisdom, flavor and essence of our struggle is not lost in translation.

Reflecting on the components of a successful political process, contemporary Cuban thinker Ariel Dacal invites us to combat the “deafening pragmatism that invites us to mutilate dreams” and implores us to build processes that are sentipensante, that is, feeling and thinking, because uniting emotion and thought brings the possibility for language to reach its full potential to tell the truth.

This task is not only the work of immigrants or minority language speakers to build. Rather, it requires a shift in everyone. We invite you to join us.

Emiliano Vera (he/they) is from Bushnell, IL and Puebla, Mexico. They are a 4th grade teacher, and organize with the Western lllinois Democratic Socialists of America as well as the University of the Poor’s Unity Across Language Committee. Emiliano is a former primary candidate for state representative in IL-93.

Natalia Fajardo (she/her), a native of Colombia, is an organizer with Vecinos Unidos in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. She is also part of the Wisconsin Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival and the University of the Poor’s Unity Across Language Committee. She likes to grow food and ride bikes.

Wonderful article you two. Makes me appreciate even more the work of the interpreters holding the glue of the movement together. Forward together 🙂