The University of the Poor Journal’s Tim W. Shenk sat down virtually with Dr. Colleen Wessel-McCoy, longtime poverty scholar, member of the Arizona Poor People’s Campaign, and author of the new book, Freedom Church of the Poor: Martin Luther King’s Poor People’s Campaign (Lexington Books / Fortress Academic, 2021). Colleen talked about the original “freedom church” from which Rev. Dr. King drew inspiration and the power of moral and religious narratives in political organizing. She spoke about lessons from the successes and limitations of the Poor People’s Campaign of 1967-68, and especially about how we can wield this movement history to inform current organizing efforts toward the June 18 Mass Poor People’s and Low-Wage Workers Assembly and Moral March on Washington and beyond.

UPJ: Colleen, it’s great to be together today to talk about the “freedom church” and the Poor People’s Campaign. Before we really dive in, can you tell us a bit about yourself and how you came to the movement to end poverty?

CWM: I grew up in Marietta, Georgia and was part of the Methodist Church just down the street from where I grew up. I jumped into everything that was on offer there. One thing they did really well was Bible study – actually reading the Bible together – and we did a lot of mission trips. We would go down to Atlanta and serve in the Open Door community there. We went to the Appalachian Mountains in North Georgia. So I got this expansive exposure to the reality that poverty is not just in one place, that it’s not just urban, not just rural.

All of this instilled in me the idea that Christianity is about care for others and service, that it’s about our neighbors. That commitment is one that I carry with me today. There wasn’t as much of an emphasis on justice, but when I was introduced to ideas of racial justice and gender justice, they made sense to me in terms of care for your neighbor. It took me a minute to integrate it, but it wasn’t like I had to leave my upbringing behind. So I trace my commitments to organizing and social change to the upbringing that I had.

One of my first days at Union Theological Seminary, there was an orientation fair in the quad, and Willie Baptist and Liz Theoharis were standing by a folding table talking about welfare rights organizing. They were talking about movement building and that those who are most impacted have to take a leading role in change. These were the early days of the Poverty Initiative, which would become the Kairos Center. My husband John and I got involved pretty quickly and ended up being mentored and formed by the Poverty Initiative and its Poverty Scholars Program, which was developing religious leadership in relationship to a movement led by the poor as a social force to end poverty.

UPJ: Talking about religious leadership in relation to movements is maybe a good way to move into the next set of questions. We talk a lot about Martin Luther King, but we don’t always talk about him as a Reverend. He must have been thinking about a lot of these questions as he began to advocate for a Poor People’s Campaign in 1967. He talked about gathering a “freedom church of the poor,” which is significant, not only because it’s the title of your book.

CWM: King was a pastor his whole adult life. For him engagement in movement work is part of the vocation of the pastor. Reverend Dr. William Barber II, who is fully a pastor and fully engaged in movement work, says that when people die because of poverty, he has to bury them. When a family’s lights get cut off, it falls on the church to figure out how to take care of that family. The minister’s call is to join the congregation in grappling with the fact that systems and structures are impacting us.

When King proposes the Poor People’s Campaign, he describes it as a “freedom church of the poor.” He’s making a historical reference to the abolitionist tradition and the Black church tradition. Religious communities, Black and white, played leading roles in the abolition of slavery in the United States. Churches and church members’ homes were stations of the Underground Railroad. Also, folks like Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman and many others spoke in moral and religious language about the abolitionists’ cause and the necessity of abolishing slavery. This leadership is also at the heart of the formation of the historically Black denominations. The African Methodist Episcopal Church and African Methodist Episcopal Church Zion were freedom churches. This “freedom church” tradition has contributed theologically, morally, intellectually, and politically to social change in the U.S.

So when King calls for the freedom church of the poor to lead the nation, he is harkening back to this tradition. His vision is that poor people are going to come together across racial and ethnic lines and from across geography, to become that leadership, that “freedom church,” that will be able to radically transform the political and economic conditions of life.

Importantly, it’s a harkening back to a successful social movement – the abolitionist movement successfully abolished slavery and the slave economy. There was a counterrevolution and a defeat of radical Reconstruction, so we’re still very much in the midst of that unfinished business. But King is making reference to a successful social movement led by the poor as a social force that reordered society. And he’s calling the poor of his day to the unfinished business of abolition and reconstruction.

UPJ: So Dr. King is invoking that history in a very conscious way. In 1968, he calls for 3,000 poor people to come to Washington to launch the Poor People’s Campaign – is that a seed of a larger movement that he’s thinking of?

CWM: Definitely. In calling for 3,000 to be the initial leadership, King invokes the biblical story of Pentecost in Acts 2, where 3,000 came together, and even though they spoke different languages, they were able to understand each other and come together as a community of believers. These 3,000 committed themselves to the movement, shared all that they had with each other and with those in need, and their numbers grew.

King talked about the initial 3,000 of the Poor People’s Campaign growing in number, forming a leadership, and being able to win the middle strata of society. His vision was that more and more people would join that initial group in Washington, get training and education, and keep growing. At another point he said that they’re going to win over the church ladies in Indiana. They might not be the people who come to Washington, D.C, but they’ll be won over by this initial leadership as the nation is made to confront the conditions of poverty, racism, and war.

UPJ: I’m guessing people who are involved in the current Poor People’s Campaign will recognize some of this strategy, that the poor need to shake the nation with their cries and make the nation confront the multiple structural crises going on that have been made out to be individual problems. But before we go to the current moment, I’d love it if you would speak a bit more about the lead-up to the 1968 Campaign.

CWM: Because so many of his past allies were resisting his call to launch an anti-war campaign to address poverty, King knew that he had to assemble a new network of organizing partners. And he assessed that it would be the poor themselves who had the most to gain and least to lose. So he called people who were already organizing around issues impacting their communities, bringing together not just individual poor people, but poor people who were already playing leadership roles in their communities. King invited these community leaders and religious leaders to a meeting in Atlanta in March of 1968. This is a historically unprecedented gathering of poor people across racial and ethnic lines – poor whites, poor Blacks, poor Puerto Ricans, poor Mexican Americans, people representing agricultural labor struggles, women from the National Welfare Rights Organization, as well as civil rights leaders. And King explicitly talked about power for poor people in this moment, about bringing people together who have common problems but who have never worked together before. I think it’s a very significant moment in history, and too often it gets lost. King was assassinated just a few weeks after that. This is a moment in our organizing work that we should pay attention to.

And yet even after King’s assassination, the people who had been in that meeting came through and brought thousands of people to Washington who made up Resurrection City. So King’s vision of bringing 3,000 people together was actually surpassed: 6,000 people were there over the six weeks, and then 50,000 marched on Solidarity Day.

UPJ: In your book, you talk about the challenges of people working together who hadn’t before. This might be one of the lessons that current Campaign leaders have tried to glean by building a multi-year campaign. This Atlanta meeting happened just two months before the 1968 Campaign was supposed to launch, and Dr. King said, “I’ve never been in a meeting like this before.” Today we have a much longer trajectory, where we’ve had almost five years since the official launch of the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival. I think there’s a real difference in working together for just a couple of months and trying to get on the same page, versus being in struggle together, getting arrested together, and being able to have the kind of trajectory of connectivity that we can have now.

CWM: That’s well said, and I think that’s true. There’s a lot that the Campaign today is able to do. One strength of the work today is the policy work: being able to pull people together around a shared set of commitments and demands, and that helps us to organize across difference. When you take on a project together like a campaign of this magnitude, working together across difference isn’t just an idea. And unity isn’t something you figure out just by talking about it. Dr. King said that when you’re marching, people begin to hold hands with people whose hands they didn’t know they could hold. We’re getting to work out what King was only beginning to initiate when he was assassinated.

UPJ: King was really going out on a limb politically by proposing to unite the poor – he was challenging a lot of his past allies. One of your book’s contributions is that it brings to light King’s unpublished speeches to his staff at the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, in the months leading up to the Poor People’s Campaign. Are there things we can learn from studying King when he’s not in the public spotlight? How is he maneuvering in this terrain and trying to unite a core of leaders to a new strategic concept?

CWM: In 1967 and even into 1968, King was trying to convince the SCLC staff about the idea of a campaign of poor people. There was not universal agreement among the staff that this was the direction they should be headed. There was not even agreement among those around King that he should be speaking out against the Vietnam War.

But King insisted on tying together the triple evils. He argued that the way you build a movement in response to the interrelatedness of poverty, racism and war is through the leadership of the poor, because they have the least to lose and the most to gain from upending the status quo on all of these issues. And so those are the people who are able to play this leading role as a new and unsettling force to take action together and win the middle. But this had to be built, and King had to win over the SCLC staff and key leaders of the civil rights movement to the necessity of a human rights movement, and win them over to the idea of organizing the poor across racial lines. In some of those internal speeches, he acknowledges how much people sacrificed in the decades of struggle they just came through, saying they had accomplished things that had been unimaginable even a few years or sometimes a few months before they accomplished them.

Then he’s calling people to take on something that is going to be an even bigger task, to take on the whole country, to address the problems of racism, war and poverty as rooted in existing structures of political and economic power. One thing that was similar in 1968 and today is that Congress and the White House were controlled by the Democratic Party. It becomes clear both in 1968 and today that this is not a movement to win the platform of the Democratic Party. We talk about our campaign not being about left or right, but about right and wrong. We’re pushing for something that’s beyond the conventional partisan split.

In King’s day, it wasn’t a popular course of action to take on racism outside of the South. He was also taking on the war machine at the height of the Vietnam War. And he was talking about millions of people in poverty, despite the fact that in the postwar period, the unemployment rate was low and the middle strata was growing. It was an uphill battle, even with his own staff. So I appreciate King’s use of theology and using biblical images, and talking in the language that would have been convincing to that group of leaders about what they were doing, including the idea that they needed to assemble a new freedom church of the poor for a new Pentecost.

UPJ: I hope people ask their libraries to buy your book. There is so much rich strategy discussion that went on behind the scenes, which you’ve been able to pull out of the archives and make come alive. I think in reading these accounts, people who are organizing now will get a much deeper understanding of the transformative potential of today’s Poor People’s Campaign. As we wrap up, what’s on your mind as you are working with people around the country toward the Campaign’s next big mobilization, the Mass Poor People’s and Low-Wage Workers Assembly and Moral March on Washington on June 18?

CWM: One of the things that I think is a strength of the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival is the leadership being developed within the states. It doesn’t all rest on the national leaders or the convergence in Washington, D.C. The Campaign is conscientious about building organizing committees in each state and using the national mobilizations like June 18th to strengthen the statewide organizing. That is an important growth from what ended up being a limitation of the original campaign.

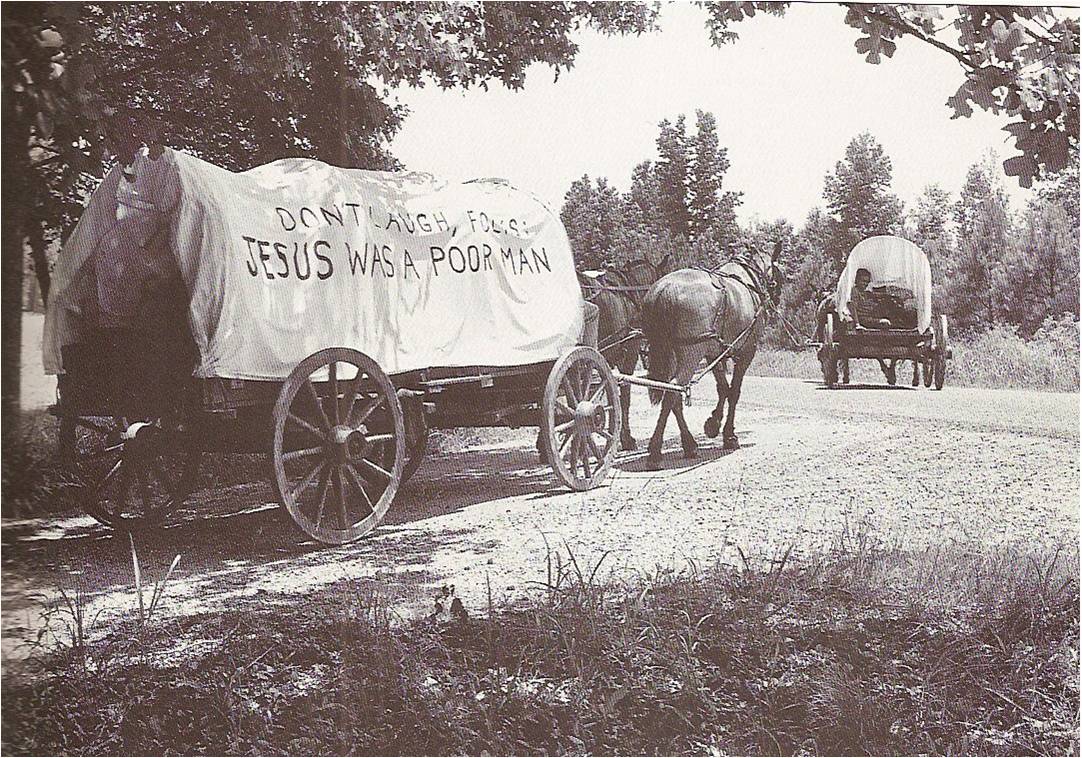

I’m part of the Arizona Poor People’s Campaign, and we’re organizing to come to Washington, D.C., and it’s always helpful for me to look at the map from 1968 to see where people caravanned from. It includes Arizona, California, Washington State. Even in that time people found a way to get all the way to Washington, D.C. I feel inspired by that.

I’m convinced that this moment, like the 1968 Solidarity Day, is similarly a historic, significant moment. Those who came to Washington for Solidarity Day and especially those who built community in Resurrection City were changed by it, and the way they organized was changed by that experience. People went home with a deeper understanding of the interconnectedness of the triple evils, and the experience broke people’s isolation. People said they were able to see each other across difference and across geography and see that they weren’t alone.

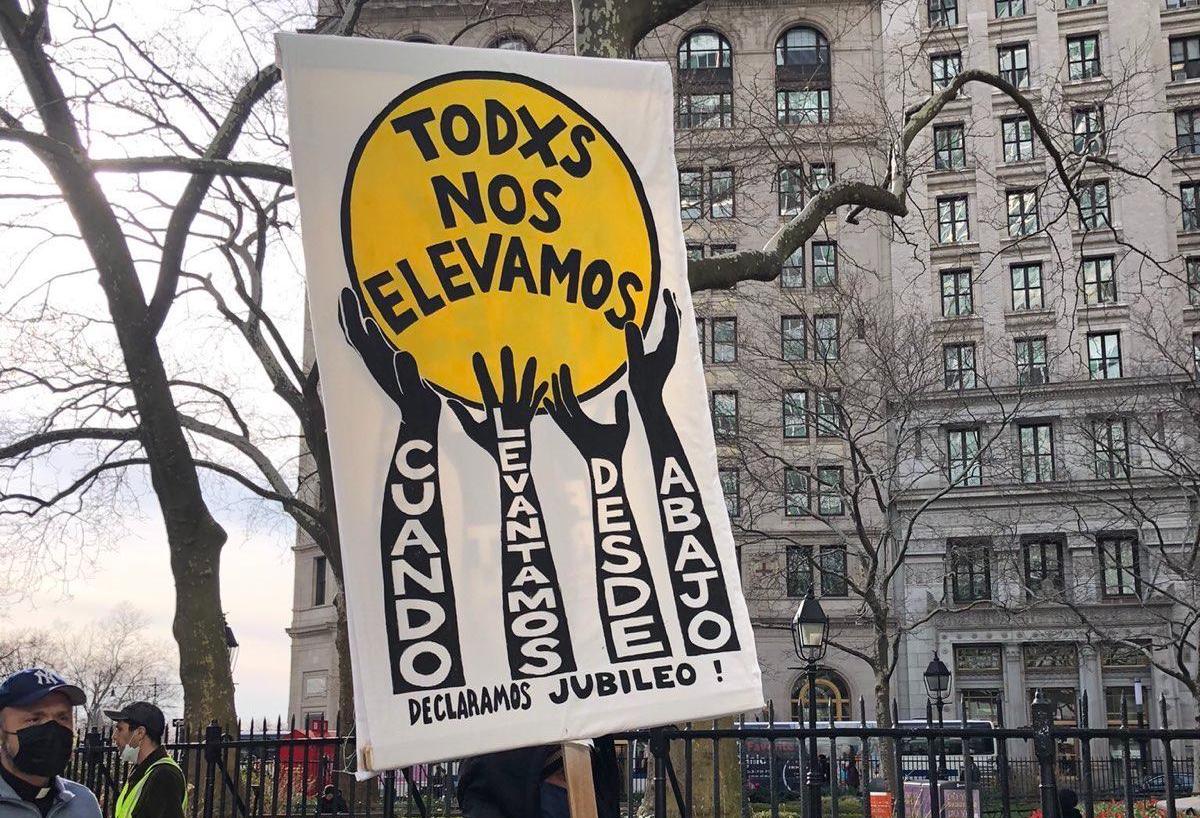

In a similar way, I think June 18th may be able to show us that we’re becoming more and more united in our organizing work, and we actually can build, and are building, a movement for the kinds of fundamental transformation that we point to in the Poor People’s Campaign. It’s very significant to show the nation that we are a huge movement of people in a huge campaign that’s part of an even larger movement of people committed to a moral revolution of values. And just as significant is that we also see each other and break our isolation by being together, and see that across the country people are doing the same thing we’re trying to do.

And then it’s about what happens after June 18. We come home strengthened to our own states and prepare for voter mobilization. And then it’s not just about voter mobilization. It’s also what happens after the elections. So we start to see that each effort builds on the last, and we begin to commit to use each mobilization to grow the campaign, find and encourage new leaders, and strengthen the movement.

UPJ: Thank you so much, Colleen! Really looking forward to seeing you in Washington.

Dr. Colleen Wessel-McCoy is author of Freedom Church of the Poor: Martin Luther King Jr’s Poor People’s Campaign (Lexington, 2021), and a Neely Visiting Professor of Religion and Public Policy at Arizona State University. She is part of the Arizona Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival and has partnered with the Kairos Center for Religions, Rights, and Social Justice for over a decade.

[…] on the heels of the Civil Rights Movement’s biggest legislative victories. At the time, King pointed out that, beneath the legal scaffolding of Jim Crow and institutionalized racism, areas in which they […]

[…] on the heels of the Civil Rights Motion’s greatest legislative victories. On the time, King pointed out that, beneath the authorized scaffolding of Jim Crow and institutionalized racism, areas by which […]

[…] on the heels of the Civil Rights Movement’s biggest legislative victories. At the time, King pointed out that, beneath the legal scaffolding of Jim Crow and institutionalized racism, areas in which they […]

[…] on the heels of the Civil Rights Movement’s biggest legislative victories. At the time, King pointed out that, beneath the legal scaffolding of Jim Crow and institutionalized racism, areas in which […]

[…] on the heels of the Civil Rights Movement’s biggest legislative victories. At the time, King pointed out that, beneath the legal scaffolding of Jim Crow and institutionalized racism, areas in which they […]

[…] on the heels of the Civil Rights Movement’s biggest legislative victories. At the time, King pointed out that, beneath the legal scaffolding of Jim Crow and institutionalized racism, areas in which they […]

[…] on the heels of the Civil Rights Movement’s biggest legislative victories. At the time, King pointed out that, beneath the legal scaffolding of Jim Crow and institutionalized racism, areas in which they […]

[…] on the heels of the Civil Rights Movement’s biggest legislative victories. At the time, King pointed out that, beneath the legal scaffolding of Jim Crow and institutionalized racism, areas in which […]

[…] on the heels of the Civil Rights Movement’s biggest legislative victories. At the time, King pointed out that, beneath the legal scaffolding of Jim Crow and institutionalized racism, areas in which they […]

[…] on the heels of the Civil Rights Movement’s biggest legislative victories. At the time, King pointed out that, beneath the legal scaffolding of Jim Crow and institutionalized racism, areas in which they […]

[…] heels of the Civil Rights Movement’s biggest legislative victories. At the time, King pointed out that, beneath the legal scaffolding of Jim Crow and institutionalized racism, areas in which […]

[…] das maiores vitórias legislativas do Movimento dos Direitos Civis. Na altura, Martin Luther King salientou que, sob o enquadramento legal de Jim Crow e o racismo institucionalizado, áreas em que tinham […]