by John Keller

This article is Part 1 of 2 and describes the economic stages in US history as seen from a “Historical Materialist” perspective. Part 2 will connect the political aspects of US history to these economic underpinnings and will discuss the political challenges we face today.

A detailed understanding of the capitalist system and its development is critical knowledge for activists. It is critical because we need to be able to explain the changes taking place in capitalism (like globalization) to our friends and associates. We also need to be able to describe the nature of socialism, its advantages over capitalism, and that socialism is a necessary outgrowth of capitalism, not a utopian dream. Far from being a dream, building a socialist society out of capitalism will be a major endeavor, just as it has taken capitalism – which emerged from feudal society – centuries to achieve its current global reach and maturity.

The Materialist Conception of History

To gain this revolutionary knowledge, we utilize an analytic framework called “Historical Materialism.” This tool helps us understand the origins and inner workings of human society. This methodology is “historical” because it explains the historical stages in the evolution of human society, from the earliest bands of hunter-gatherers, through tribal organizations, ancient city states, feudalism, capitalism, and socialism. Each of these stages is built on a distinct type of economy, with distinct social and political structures as well. Each of these stages represents a distinct “political-economic formation.”

This method can also differentiate sub-periods within the development of a political-economic formation, such as different historical periods within the period of capitalism itself. These sub-periods represent different “political-economic stages” that develop within a political-economic formation. As will be discussed below, in 300 years of US history there have been five distinct stages in the evolution of capitalism.

This methodology is also “materialist” because it shows that changes in the material or economic life of people result in changes in social organization, which in turn fosters changes in political life. In the economic sphere, the “means of production” (technology, materials, and sources of energy) develop through human invention. Economic advances can result in changes in the social sphere, called the “relations of production” (how work is organized, how property rights are defined, and how class stratification develops). Similarly, changes in social relationships can give rise to changes in the political “super-structure” of society (including changes in ideas and philosophies, political parties and ideology, religious beliefs, and in the institutions of government that protect property and class entitlements).

To summarize the structure of a political-economic formation: political organization and activity are an extension of the social relations of production, and social relations are an extension of the means and methods of production.

Primary and Secondary Dynamics

It is also true that political systems can exert a secondary influence on social relations of production which in turn can exert a secondary influence on the development of the means of production. This is consistent with modern systems theory that recognizes that feedback can occur between elements in a system. Nevertheless, Historical Materialism recognizes the primacy or governing influence of the economic means of production on social relations of production through to the political and ideological super-structure, with feedback being a secondary phenomenon. In other words, each element in a political-economic system is a direct reflection of the one below it, yet each element can influence – retard or accelerate – the development of the element below it, but cannot determine its fundamental nature.

Political-Economic Stages in US History

In US history there have been several major shifts in economic, social, and political organization. Each of these periods is characterized by new, life-changing inventions in the means of production. This has been typically followed by the emergence of a new class of owners of these technologies. In turn, this new class of owners have their own self-interests, so they seek dominance in the political arena to protect their interests. Apart from them stands a working class that also seeks to protect its own interests through various forms of organization and activity. These would include historic actions like abolition and emancipation, unionization, votes for women, desegregation, unfettered enfranchisement, building an independent party of labor, and even revolution against intolerable living conditions.

The periods of distinct political-economic formations in US history are delineated by the rise of new technologies (means of production) that eventually surpass older technologies in economic importance. Several related technologies may develop together, and these constitute an “Economic Complex.” The succession of distinct economic complexes in US history could be defined as follows:

- Independent Household Complex: The initial complex of predominantly family farming, plus some household industry and mercantile trading began with the British colonization of the East coast of North America in the 1600s.

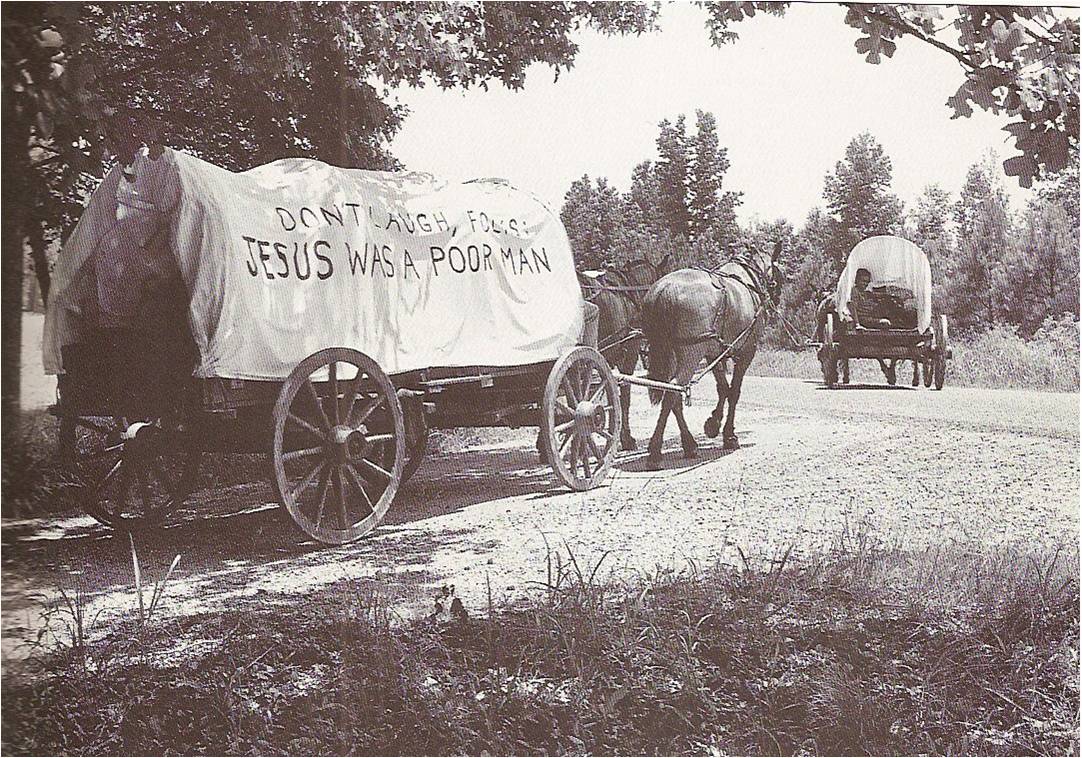

- Cotton Complex: The second complex began developing while the first was still dominant. This new complex revolved around “King Cotton” and other plantation crops. Following the invention of the cotton gin in the 1790s, plantation agriculture and slavery grew quickly. By 1820 the capital invested in slave labor alone was greater than any other economic activity in the US.

- Railroad Complex: The third complex began to emerge in the same pre-Civil “King Cotton” period. It was marked by the development of the steam engine and related industries like coal and iron ore mining, iron works, and eventually smelting. After the end of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, cotton production collapsed, and by 1875 more capital was invested in steam railroads (including boilers, rails, wheels, boxcars and coaches) than in any other industry in the US.

- Mass Manufacturing Complex: The elements of the fourth technological complex emerged in the late 1800s while railroads were still the dominant industry. These new technologies set the stage for the mass manufacturing complex. The new inventions supporting this complex included the automobile (initially steam-powered), the combustion engine, autos, and aircraft (all reliant on oil drilling and refining), lighting, telephones and radio (underpinned by a new force called electricity and by vacuum tubes), and of course the assembly line (first powered by steam engines and ultimately by electric/mechanical motors). By 1915, capital invested in manufacturing easily surpassed that invested in railroads.

- Financial Complex: The manufacture of weapons for two World Wars extended the heyday of mass manufacturing beyond 1945. But New Deal deficit spending during the Great Depression had already pumped huge amounts of money into circulation through the banking system (just as with Covid funds today). By 1940 the amount of capital held by banks had surpassed the amount of capital in all manufacturing industries combined. In the 1950s, these loanable funds – in conjunction with additional government deficit spending – supported the expansion of Cold War defense companies, enabled the prosecution of the Korean and Vietnam Wars, and supported the so-called War on Poverty.

- Technology Complex: But while the Cold War was raging, a new Technology complex began to emerge. It started with the invention of semiconductor chips and central processing units to replace outdated vacuum tube technology of the early 1900s. Major funding of R&D by government and industry led to the initial use of semiconductors in fighter planes, missiles, and space exploration. These expenditures brought down the cost of production and laid the foundation for the proliferation of modern consumer electronics, including personal computers and cell phones. By 1990 the capital invested in the technology industry overtook the capital in banks. In this period – indeed in every period with a major war – the stimulative feedback potential of government spending on economic development becomes quite clear.

Looking Forward

Each of these technological periods engendered changes in relations of production. In every instance a new class of owners of these technologies emerged and contested with each other for control of the central government and its budget, purchasing power, research funding, and tax-exemptions. Likewise, each period witnessed changes in the nature of the labor force and its organization (or lack thereof). The abolition of slavery ended the Cotton period. Mine workers and steel workers organized unions in the Railroad period. The explosion in Mass Manufacturing suffered initially from labor shortages, but rural migration to cities, the movement of African Americans in the South to northern and western states, and heavy immigration from Europe resulted in a large, diverse working class whose sectarian divisions posed a challenge to their ability to further unionize or to exert their political independence through a third party movement.

Yet in the new Technology age, there are nascent signs of workplace organization centered in the dominant service industries. In capital’s search for lower wages and higher profit margins, much technology production has been relocated in China and other countries. The manufacturers that survived the Rustbelt implosion in the 1970s have been busy automating the work left behind. And much of the US workforce now consists of low-paid unskilled service workers, the impoverished working poor, the permanently unemployed, and the chronically homeless.

The burning question posed by Historical Materialism is what the next transformation in society will be? New forces of production are already emerging – including renewable energy, instantaneous social communication, virtual reality, crypto-currencies and blockchain applications. Will these tools remain the property of private owners for their own enrichment? Or can we shift control to the public sector – not for profiteering but for universal social benefits in the form of truly full employment, universal healthcare and education, safe affordable housing, and a country and world that is well-fed? In other words, can we agree to work toward complete social justice and away from private wealth? And if so, how do we do it?

Part II of this article will explore the political opportunities that each economic period has presented in the struggle between labor and capital, and what opportunities exist today.

John Keller is a graduate of Stanford University and holds a Phd from U of Michigan and an MBA from U of Massachusetts. He has taught at the University of Michigan, Central Michigan University, and Mount Holyoke College.

In the mid-1970s John worked in the semiconductor industry in Silicon Valley as a production line worker and as a maintenance mechanic. His groundbreaking dissertation – “The Production Worker in Electronics” – documents the early years of the semiconductor industry in the US, with a focus on the creation of its work force of mostly women who migrated to Silicon Valley from Pacific rim countries.

John is also the author of Power in America: The Southern Question and the Control of Labor, which analyzes the unique history of the US South and its lasting role as a bastion of conservative political power in the US.

[…] John KellerPart 1 of this article explained the analytical framework called “Historical Materialism” and how to […]