By John Keller

Part 1 of this article explained the analytical framework called “Historical Materialism” and how to use it to understand patterns in U.S. history. In that part, I described the general structure of any class-based society and discussed the three basic components of such societies:

- The material Means of Production (technology, materials, skills, the methods of organizing work, etc.). These are the means that assure survival but also for creating usable commodities.

- The social Relations of Production define who owns the means of production and its output. If commodities are created by, but not owned by labor, then class distinctions occur and conflicting class interests become the drivers of political life.

- The political Superstructure (the State, its agencies, political parties, ideologies, etc.) is a specialized form of organization for enforcing property rights and thereby maintaining class stratification.

- Woven together, these three elements constitute a Political-Economic structure with features that are unique in different historical periods.

In US history there have been six major shifts in the political-economic structure of capitalism. Each of these periods has been characterized by new, life-changing inventions in the means of production, followed by the emergence of a new class of owners of these technologies and a renewed class of wage workers with new skills and unique forms of organization (unions, third parties, etc.). Because the capitalist system operates unevenly (with recessions) and distributes wealth unevenly (during expansions), challenging living conditions can give rise to popular political demands for reform of the system, or even a challenge for control of the government itself (the State).

This article will focus on two periods in US history that saw an upsurge of independent political activity, the formation of Third Parties, and the challenges they posed to property rights and the existing government. From this we expect to learn about some of the dynamics of the Superstructure and to list some of the lessons to be learned about working in the electoral arena. This is pertinent to our own work around the 2022 midterm elections and the 2024 elections. It is also pertinent because gains are being made worldwide by hard-line, autocratic politicians in their electoral arenas. Our challenge is to engage in the electoral arena, to develop demands, to continue organizing the poor in the process, and to develop leaders prepared to continue the class struggle.

Case 1 – The Rise of the Republican Party Before the Civil War

In 1850 the two major parties were the Whigs and the Democrats. But segments of the population were restive and looking for the resolution of two seemingly unrelated issues. First, Christian communities in the North and South began agitating for the abolition of slavery in the southern states. At the same time, the rural populations of the Midwest pushed the US government to open more lands to the west for new farmers to settle and develop. But this “Free Soil” movement was stymied by the representatives of Southern planters in the US Congress. Instead, the South favored opening these new lands as states where slavery would be officially recognized and that the planters could colonize and dominate. This insistence on maintaining the legitimacy and spread of slavery was adamantly opposed by the Abolitionists.

Both the Free Soilers and the Abolitionists organized as small political parties in order to pursue their separate goals. The Free Soil Party were not explicitly anti-slavery – they just opposed the South blocking agricultural expansion westward. Eventually, Free Soilers and Abolitionists realized that their interests were in alignment. Achieving the demands of both groups required breaking the political power of the plantation-based “Bourbon” Democrats. Popular Interest in the demands of both small parties became the foundation for a new political party – the Republican Party. In just ten years, the Republican party grew dramatically, supplanted the Whigs as the opposition to the Democrats, and achieved the election of a Republican president and Congress in 1860. At this point the Southern states seceded, formed the Confederacy, and the country went to war. The North fielded two armies – the Army of the Potomac (drawn from Eastern recruits) and the Army of the Tennessee (drawn from Midwestern recruits motivated to fight for Free Soil).

This historical example shows that with a major unifying cause, a third party can develop into a powerful political voice for its adherents. But it can also cut both ways; beginning in the 1960s, several southern-based third parties appeared, including George Wallace’s American Independent Party. Their platforms were throwbacks to segregation and voter suppression, in reaction to the legislative victories of the Civil Rights movement.

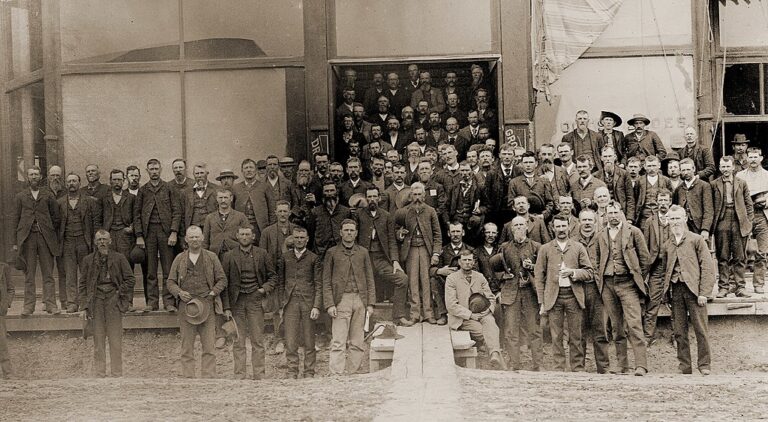

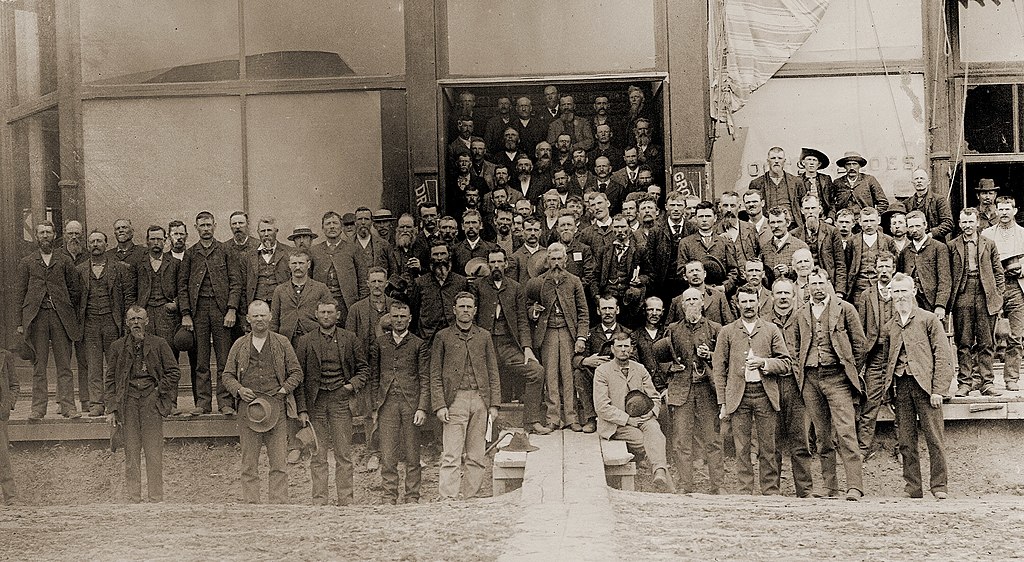

The People’s Party in the late 1890s (aka the Populist Party)

Another important third party moment in US history occurred during the maturity and eventual decline of the power of Railroad capital in the US economy and politics. During the 25 years between 1873 and 1897, there were 13 years of economic contraction, including two major depressions. This economic crisis was driven by the economics and policies of Railroad capital itself. Interestingly, the major player in this revolt against capital was once again the farm population of the Midwest, the descendants of Free Soilers who fought politically and militarily to open the Midwest and Great Plains for settlements.

After the Civil War, aspiring farmers finally got their lands, but there was a catch. As Midwestern and Eastern cities grew in size, the demand for food from the grain belt accelerated. The new expanse of farms proved productive enough to meet this urban demand, but the only way to get these foods to the city markets was by train. The railroad operators saw in this dependence a chance for increased profits to pay down huge debts accumulated in building out the rail system to the west and south. All they had to do was raise – and then raise again – freight rates paid by farmers and grain co-ops. Many farmers had to mortgage their farms to cover higher operating costs, and eventually many small farms were bankrupted.

As farms defaulted, banks repossessed the properties and resold the lands at a profit to speculators and even to the railroads themselves. Farmers began to organize to stop this wealth transfer. One key demand was federal regulation of the railroads as utilities, including controlling freight rates. Organizations called Farmers’ Alliances appeared in the Midwest and allied themselves with workers in the railroad industries in Chicago. In the South farmers suffered the same fate as the Midwesterners. They too formed Farmers Alliances, sometimes along color lines. Eventually, the three sets of alliances formed a national Farmers Alliance to face the railroads as a united front.

In the Midwest, the Alliance ran candidates in local and state elections. They won four governorships in Plains states and gained control of the legislature in Kansas. In the South, the Alliance chose to run “fusion” candidates within the existing state Democratic Parties, but with the same Alliance platform. Sometimes this required getting the buy-in of some long time, sympathetic Democrats. But even this procedure generated some electoral success. These victories convinced Alliance leaders that they could form a successful third party and in 1892 the People’s Party (aka the Populist Party) was formed.

The People’s Party constructed a broad farmer-labor platform with many progressive planks, including:

- Government ownership and administration of the railroads

- Nationalization of the telegraph and telephone

- Public ownership of all utilities

- State owned grain elevators

- An expansion of currency in circulation backed by silver, not gold

- Increased use of public referendums

- Laws for protection of workers

- Universal compulsory education

- Abolition of sweatshops

- Employer’s liability for job-related injuries

In 1894 – in the midst of a Depression – the People’s Party ran candidates at the local, state, and federal levels. They won more votes nationwide than during their initial 1892 campaign, and outnumbered Democrats 2:1 in the North Carolina legislature. But true success was achieved in the 1896 campaign. Both the People’s Party and the national Democratic Party nominated William Jennings Bryan, a preacher’s son and brilliant orator, as their candidate for President in 1896. He garnered 47% of the national vote and won 22 states with 171 electoral votes. And they were most successful in the deep South, the Plains states, and the Mountain states. Their success set off alarms about the potential demise of capital and its representatives.

Lessons Learned from the Populist Movement

Amazingly, 1896 marked the high point of the Populist flood; Populism receded as quickly as it had risen. Numerous factors led to the decline of the People’s Party and many lessons can be drawn from this experience:

The Populists learned – when Bryan died unexpectedly and there was no equally strong leader to replace him – that a party needs a bench of capable, well prepared leaders.

The Democratic Party learned the importance of labor reforms to the perpetuation of the system, so they co-opted some of the Populist labor demands into their own platforms. This created the template for New Deal legislation in the 1930s.

Republicans learned that the citizenry hated monopoly industries and their abuses, and that to avoid any further attempts at nationalization, rapacious monopolies and trusts would have to be regulated in at least some fashion (thus laying the basis for Republican reformism exemplified by the “Progressive” Teddy Roosevelt in the early 1900s).

The southern Populists learned that running “fusion” candidates within the Democratic Party yielded mixed results, since some of their sympathetic “fusion” brethren were never really committed to the Populist platform and simply “changed their minds”. But despite defections, Populist politicians in the South remained stronger than the conservative “Bourbon” wing of the Democratic Party through 1920.

The conservative Dixiecrats learned that both black and white farmers could unite behind a common progressive cause, and that this threatened the power of conservatives. As they regained the upper hand over southern Populists, they began implementing new voting restrictions and segregation policies, thus blocking any future alliances between white and black labor in the South.

Some Populists in the Midwest learned to reorganize under the banner of Farmer-Labor parties to carry on their work, including within the national Democratic party – a tradition that continues through today.

And lastly, other Populists learned about other important labor issues facing their urban railway worker compatriots. Some were also introduced to the ideas of socialism and left to join Eugene Debs’ Socialist Party, 1/6th of whose membership were farmers.

In sum, the history of the national Farmers Alliance demonstrates that compelling progressive issues can unite voters across region, race, class, and even party lines. Such issues – really our issues – can achieve wide notice and have organizational effect when aired effectively in the electoral arena and in the platforms of third parties. But we are playing catch-up. Beginning in the 1970s, the Republican party created its own version of “unifying” politics – based on nativism, racism, evangelism, and the rejection of scientific thought – and successfully linked its rural Midwest, Plains, and Mountain states constituency with its usurped conservative Southern base. These former bastions of the People’s Party and its progress platform have been turned upside down. This must be countered and the electoral arena – guaranteed in the Constitution – is one of many fronts we must work on.

John Keller is a graduate of Stanford University and holds a Phd from U of Michigan and an MBA from U of Massachusetts. He has taught at the University of Michigan, Central Michigan University, and Mount Holyoke College.

In the mid-1970s John worked in the semiconductor industry in Silicon Valley as a production line worker and as a maintenance mechanic. His groundbreaking dissertation – “The Production Worker in Electronics” – documents the early years of the semiconductor industry in the US, with a focus on the creation of its work force of mostly women who migrated to Silicon Valley from Pacific rim countries.

John is also the author of Power in America: The Southern Question and the Control of Labor, which analyzes the unique history of the US South and its lasting role as a bastion of conservative political power in the US.