by Jamie Blair, Joyce Brody, Lenny Brody, and Dan Jones

As we discussed in the December 2021 Political Report, we are living in a time of worsening, compounding crises – an economic crisis that is no longer simply cyclical but structural, interwoven with a global pandemic, new and ongoing war, environmental crisis and a legitimation crisis of the political system. These crises and the spread of poverty across the world are creating the conditions for more and more people to see that the current system is not working. These developments confirm the University of the Poor’s focus on the importance of organizing and educating the poor and dispossessed masses as the leading social force. The first step in accomplishing this task is developing and uniting the leaders of the poor as revolutionary cadre.

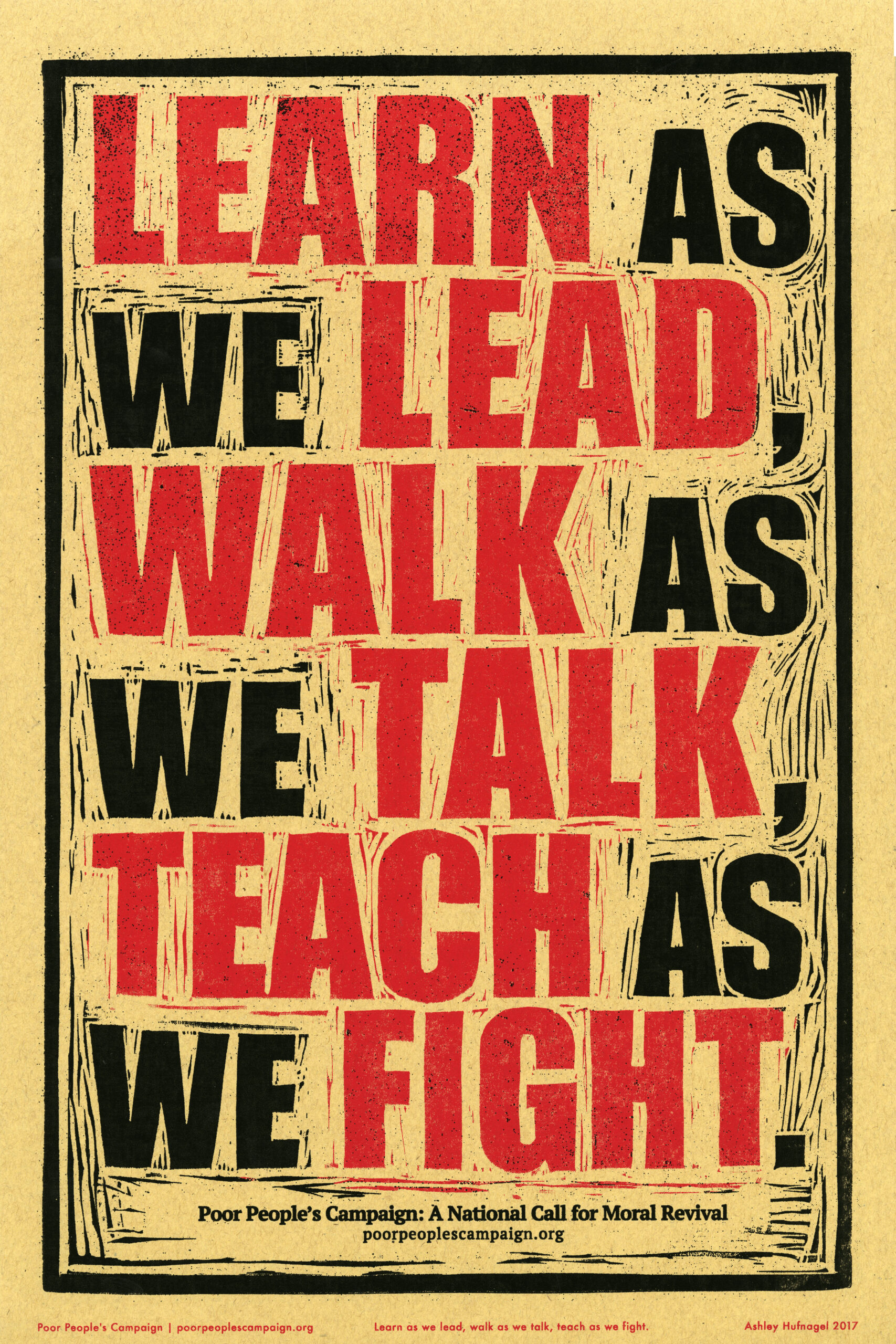

Our enemy is always studying past periods of crisis and transformation, in order to guide their attempts to prevent any independent movement of the poor from coming together. Studying the history of this country can help us understand and anticipate their moves, and help us identify key levers for moving the nation along the path toward fundamental transformation led by the poor. These key levers are the battle for the Bible, elections & the electoral arena and the South. With the growth, development and maturing of the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival, our class has an increasingly powerful vehicle, engaged in these key areas, in building the movement to end poverty.

The Poor People’s Campaign and the Bible, the Ballot, and the South

The revolutionary process of every country is shaped by the history and culture of that country. In the United States, the path to fundamental change goes through the battle for the Bible; the skillful use of elections and the struggle for the ballot; and the reemergence of a powerful, politically independent, multiracial movement of the poor in the South. In each of these areas and in their interconnection, the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival is on the leading edge.

For the University of the Poor network, we have to fully appreciate these breakthroughs and embrace and support them. A basic contradiction of our political situation today is that while the poor are in the most revolutionary position in society – having the least to lose and the most to gain from ending the dictatorship of the wealthy – they are also the most disorganized, disunited, and segregated group. But the history of this country teaches us that religious movements and agitation, electoral campaigns, and Southern upsurges are the keys to the emergence of a new consciousness, to shifting the balance of forces and to building multiracial organization of the poor.

This understanding comes from our study of key moments in US history that have the most to teach about how the poor can accumulate that unity of consciousness and action that would allow them to overthrow the power of capital: The movement to end slavery and the Civil War (1830s-1860s), the struggle for Reconstruction (1860s-1890s), the 1930s, and the 1960s.

Abolition, Reconstruction, the 1930s, and the 1960s

In their struggle against the Slave Power, the leaders of the Abolitionist movement – North and South – focused much of their attention on the struggle against the religion of the enslavers: organizing freedom churches among enslaved Black workers, pushing religious denominations to take stands against the ownership of human beings as property, and publishing and distributing hundreds of thousands of copies of pamphlets and books with titles like “The God of the Bible against slavery.”

Beginning in the 1840s and 1850s, leading Abolitionists took up electoral organizing as a powerful tool to split the existing political parties and to create an alignment of their own bases, Northern industry, and Western farmers all against the Slave Power. Looking South, without the survival organizing and insurrections of enslaved Black workers in the South the growth of the anti-slavery movement would have been impossible. During the Civil War in particular, it was the general strike of enslaved Black workers in the South that forced the transformation of the war’s political aims from saving the Union to abolishing the Slave Power, and which dealt the decisive blow to the Confederacy.

Later, during the long struggle for Reconstruction after the war, elections served as powerful vehicles to take steps toward the unity of Black and white labor in the South. But it was the failure to form a nation-wide party uniting labor, white and Black, North and South, that cleared the way for the rise of Wall Street imperialism and the counter-revolution of property in the South. Du Bois summed up this failure of the working classes in the North and Midwest to appreciate the importance of the South and of the battle for the ballot in his book Black Reconstruction in America, saying:

“The South, after the war, presented the greatest opportunity for a real national labor movement which the nation ever saw or is likely to see for many decades. Yet the labor movement, with but few exceptions, never realized the situation. It never had the intelligence or knowledge, as a whole, to see in black slavery and Reconstruction, the kernel and meaning of the labor movement in the United States.”

And further:

“In the North, a new and tremendous dictatorship of capital was arising. There was only one way to curb and direct what promised to become the greatest plutocratic government which the world had ever known. This way was first to implement public opinion by the weapon of universal suffrage—a weapon which the nation already had in part, but which had been virtually impotent in the South because of slavery, and which was at least weakened in the North by the disfranchisement of an unending mass of foreign-born laborers. Once universal suffrage was achieved, the next step was to use it with such intelligence and power that it would function in the interest of the mass of working men.

“To accomplish this end there should have been in the country and represented in Congress a union between the champions of universal suffrage and the rights of the freedmen, together with the leaders of labor, the small landholders of the West, and logically, the poor whites of the South. Against these would have been arrayed the Northern industrial oligarchy, and…the representatives of the former Southern oligarchy.

“This union of democratic forces never took place…”

The 1930s and the New Deal period also demonstrate how the ruling class uses the electoral arena and Southern politics to maintain its iron grip on the political control of the country. In the late 1920s and early 1930s Farmer-Labor parties had been organized, especially in the Midwest, and played an influential role in the elections. Upton Sinclair’s End Poverty in California (EPIC clubs) became a powerful force in the state’s politics. Both these movements and other impulses toward working class political independence were blocked and co-opted by the Democratic Party. In an attempt to become “influential” organizers assisted in leading activists into a junior partnership within the Democratic Party. Thus the powerful movement of the 1930s was dissipated and unable to survive the immense repression that came after World War II. The key to ending the threat of the growing class conscious labor movement was again the abandonment of efforts toward multiracial unity of the poor in the South, and the abandonment of the struggle for universal suffrage and other political rights for Black workers, leaving the region in the hands of the Southern racist Dixiecrat wing of the New Deal coalition.

During the 1950s and 60s, the powerful upsurge of the Civil Rights movement was able to break through the anti-Communist and Jim Crow political terror. It was able to do this, much like the Abolitionist movement had, through initiating a struggle over the meaning of the Bible and the Constitution. However, as the movement gained power and prominence, and threatened to unsettle the whole nation and unite the bottom, again the ruling class manipulated the class struggle and led activists into the arms of the Democratic Party. Northern liberals and the Democratic Party politicians like the Kennedy brothers and Lyndon Johnson positioned themselves as the only allies of the Civil Rights movement. And again the organizers, rather than fighting for a Southern movement of the poor, both Black and white, took part in an alliance where Black activists fought and died while northern liberals became the “political” leaders of the movement. With the assassination of Martin Luther King and the ruling class repression of other leaders, the movement was unable to further develop.

After the defeat of Reconstruction, the Democratic Party control of the South facilitated the ruling class control of the country for almost 100 years. For the last 50 years control of the South and of the nation has operated through the powerful Republican Party in the South together with the inept Democratic Party. The alliance between the representatives of Wall Street in the Republican Party and sections of white labor, particularly in the South, was forged through the ideological weapons of white supremacy and a Christian nationalism that is the direct descendant of the Slave Power’s theology.

The Significance of the Poor People’s Campaign

Today, the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival is advancing a Biblical interpretation and a religious practice that puts the struggle to abolish poverty at the center of the country’s moral concern, and identifies faith with taking the side of the poor. We should study the experience of the Abolitionist movement closely, and the priority they placed on convincing the broadest possible sections of society that Christianity was incompatible with the enslavement of human beings, through the use of press, pulpit, and protest.

We are in the period of primary elections leading up to the mid-term elections and the 2024 presidential elections. The challenge for us is how to develop powerful, politically independent organizations of the poor within the intensifying electoral conflicts in the US. And the campaign is carving a new path through the poisonous swamp of the country’s partisan politics, summed up best in the slogan of “mobilize, organize, register, and educate for a movement that votes.” In essence, the campaign is building an independent national electoral organization, built around the program of the poor. It is using elections as opportunities to take a leading role in the coalition opposed to reactionary politics and Democratic spinelessness, challenge the dominant narratives, and connect with and organize large numbers of poor and dispossessed people – especially those who have been excluded from and discouraged by the usual two-party politics. It is organizing them not into the Democratic Party but into the Poor People’s Campaign, which has its own political platform and its own methods and organization for building and wielding political power.

In the South, the campaign is bringing the region’s long tradition of multiracial organizing among the poor into our new era with its call to build statewide moral fusion movements. Today, as in the past, there is no path to accumulating the power that the poor and dispossessed need without breaking the stranglehold of the ruling class on Southern politics. The South is the most important region in the battles for the Bible and for the ballot, and is also the poorest part of the county.

The Republicans are counting on their ability to intensify their Southern strategy and maintain the region as a bastion of reactionary politics. The section of the Democratic Party most closely tied to Wall Street is relying on its Southern organization to undermine the growth of the party’s progressive wing. We saw this in the 2020 Democratic primary, when the intervention of South Carolina congressman Jim Clyburn played a significant role in blocking Bernie Sanders’ campaign and throwing the nomination to Joe Biden. The attempt to narrow and isolate the struggle against voter suppression, cutting it off from all of the issues impacting the poor in the South, is another example. It’s the Southern work of the Poor People’s Campaign, including its electoral organizing and outreach to poor and low-income people in communities that are often ignored or written off, that represents the most promising counter to both of these strategies.

The unity and leadership of the poor in the United States — power for poor people — will be won and wielded in the struggle over religion and over the meaning of democracy, in the electoral arena and the battle for the ballot, and in the fight against the color line and cruel manipulation of the poor in the South. Expanding and translating the politically independent organization of the poor into real political power depends on major breakthroughs in these areas, and that process and promise is the greatest significance and contribution of the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival today.

Jamie Blair is a lifelong Pennsylvanian and member and leader of Put People First! PA (PPF-PA). After getting the incredible opportunity to represent PPF-PA on the Che Guevara Internationalist Youth Brigade to Venezuela in 2020, Jamie joined the UPoor’s Proletarian Internationalism Taskforce and more recently the Political Coordination Committee.

Joyce Brody is a mother, grandmother and has been a community and political organizer for almost 50 years. She was a founding member of the Communist Labor Party and is a retiree of Workers United Union. Currently she is an Executive Committee member of the United Neighbors of the 35th Ward in Chicago, tri-chair of the Illinois Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival and a co-coordinator of the University of the Poor’s Political Coordination Committee and Standing Committee.

Lenny Brody has been politically active since the early 1960s. During the mid-1960s he was a volunteer with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the civil rights organization led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in South Carolina. As part of his activities in protest of the Vietnam War he refused induction into the Army. He was a founding member of the Communist Labor Party and has studied economics and theories of political change while continuing his political activism. Currently he is one of the coordinators of the University of the Poor Think Tank and a member of the University of the Poor Journal.

Dan Jones is a member of the University of the Poor Political Coordination Committee and a Co-Chair of the Florida Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival.