by Luis Rodriguez

“To be radical is to grasp the root of the matter. But, for man, the root is man himself.”

Karl Marx

In 2014, I managed a seemingly crazy move, against all odds, and with literally no chance of success: I ran for governor in the most populous, costliest, and economically divided state in the country, California.

I decided to do this at a time when every political party and movement in the U.S. was steeped in crisis. When society was rent with irreparable economic and political ruptures, including a massive mortgage and financial calamity that began in 2008. When archaic industrial capitalist models, concepts, and modes of operation were dying, and new forms of organization, relationships, and governance struggled to be born.

I couldn’t do this without the support of the community, centered around Tia Chucha’s Centro Cultural & Bookstore. The Centro made the arts a transformative and healing power for around 15,000 people a year in a community of half-a-million that, until we opened our doors, did not have a bookstore, art gallery, movie house, or complete arts and media center. Although the Centro didn’t officially endorse me or use its funds or offices for the campaign (it’s a tax-exempt corporation), I ran knowing the space would suffer. By then I’d become the Centro’s main outreach person and fundraiser, although my wife Trini and her staff were the ones who actually made everything happen.

In 2012, I had already run for U.S. Vice President with Salt Lake City’s former mayor Rocky Anderson under the U.S. Justice Party. I had traveled to a few cities and gotten coverage in important progressive media outlets like Pacifica’s “Democracy Now!” Rocky represented a strong voice against the corruption of money in politics and the “Duopoly” of the two-party system masquerading as choice. The Justice Party was able to make the ballots of 15 states, and write-in status in 15 additional states, and garner around 40,000 votes in the national election.

So, in 2014, just as I had turned 60, I embarked on a new campaign. At the time I felt that with more than 40 years of revolutionary teaching, organizing, and writing under my belt, I had to take all this to heightened levels of influence, possibility, and impact.

I decided to do this from a platform, the electoral, which for the most part had lost relevance in the country, again with the “one-party system” (flaunted as two) controlling who ran, who spoke, and who got elected. It was a feeble and largely inept space, but one I didn’t think should be turned over to so-called conservatives and liberals without a fight. Revolutionary visions, new ways of thinking and going, were being pushed aside everywhere — even though they were needed more than ever.

I’m not exaggerating when I say democracy had been bought and sold.

By then the Democratic and Republican parties had become drenched with big money. With the 2010 Supreme Court ruling in Citizens United vs. Federal Election Commission upholding the “rights” of corporations to make political expenditures, obscene amounts of capital entered into even the smallest and seemingly inconsequential elections. Campaign financial reform arose to limit the way corporations, banks, and lobbyists swayed and controlled the American vote. The more control big money had in voting, the more removed the process had become for the majority of the American electorate, especially its working class, now being driven to abject poverty and homelessness. The pervading economy in the country’s most deprived areas was dominated by Walmart, which became the largest employer in many of the formerly industrial and agricultural powerhouse states of the Midwest and the South.

In California, this took the shape of the sixth largest economy in the world, in the most developed and wealthiest state, still having a 24% poverty rate; at the time higher than the poverty rates of Mississippi and Georgia. It took the shape of a multi-billion dollar prison industry that garnered more tax dollars than colleges and universities. It took the shape of “fracking” (hydraulic fracturing) that poisoned land and water tables with up to hundreds of cancer-causing chemicals and tons of gallons of water blasted to extract oil from shale, while major energy companies were able to extract immense profits. It took the shape of the state with the most immigrants in the country, yet with increased deportations, the building of privately owned detention centers, and major businesses, particularly in agriculture, dependent on low-paid migrant labor. It took the shape of a state with the largest defense industries plying for a war economy while core urban areas became battlegrounds for street and drug gangs — with law enforcement agencies as the largest “gangs” to curtail them.

I felt I had an imagination for a new California, which became our campaign’s tagline.

I asked my comrade and friend of four decades, Anthony Prince, a revolutionary lawyer and working-class strategist, to be campaign manager. We had a number of volunteers meet regularly at a guesthouse in my backyard. We embarked on a journey of no return — with little funds (around $30,000 at the end) against an array of 15 candidates, whose frontrunners had up to $20 million at their disposal. We ran against a relatively popular sitting governor, Jerry Brown, on his fourth run for the office since he first became governor in 1975.

In tiny and cramped rented cars, Tony and I (as well as leaders from the activist community of the Northeast San Fernando Valley) drove up and down the state a dozen times; to the Central Valley, the Sacramento Delta area, the Bay Area, Southern California, including the border area, coastal cities, and deserts. We faced a new primary race where only the top-two candidates (regardless of party) could compete in the general election. Of course, I refused corporate funds. We had to go grassroots all the way.

Since party-nominated candidates were no longer allowed to run, I had to get the endorsements of important parties and organizations. Even though I ran as an “independent” I received the invaluable endorsements of the California Green Party, the U.S. Justice Party, the Mexican American Political Association, and El Hormiguero (The Anthill), among other individuals and organizations. Even the “Godfather” of Chicano Studies, Professor Rudy Acuna, who rarely gave such support, endorsed me.

Although I had a hard time getting major media attention, since my “money” didn’t talk loud enough for them, I did manage coverage in Huffington Post, Fox News Latino, Los Angeles Times, Truthout, Mint Press News, Orange County Weekly, Monterey County Weekly, San Francisco Bay Guardian, Truthdig, KPFK, Radio Bilinque, Monterey Herald, Daily Californian, Univision, La Opinion, and others.

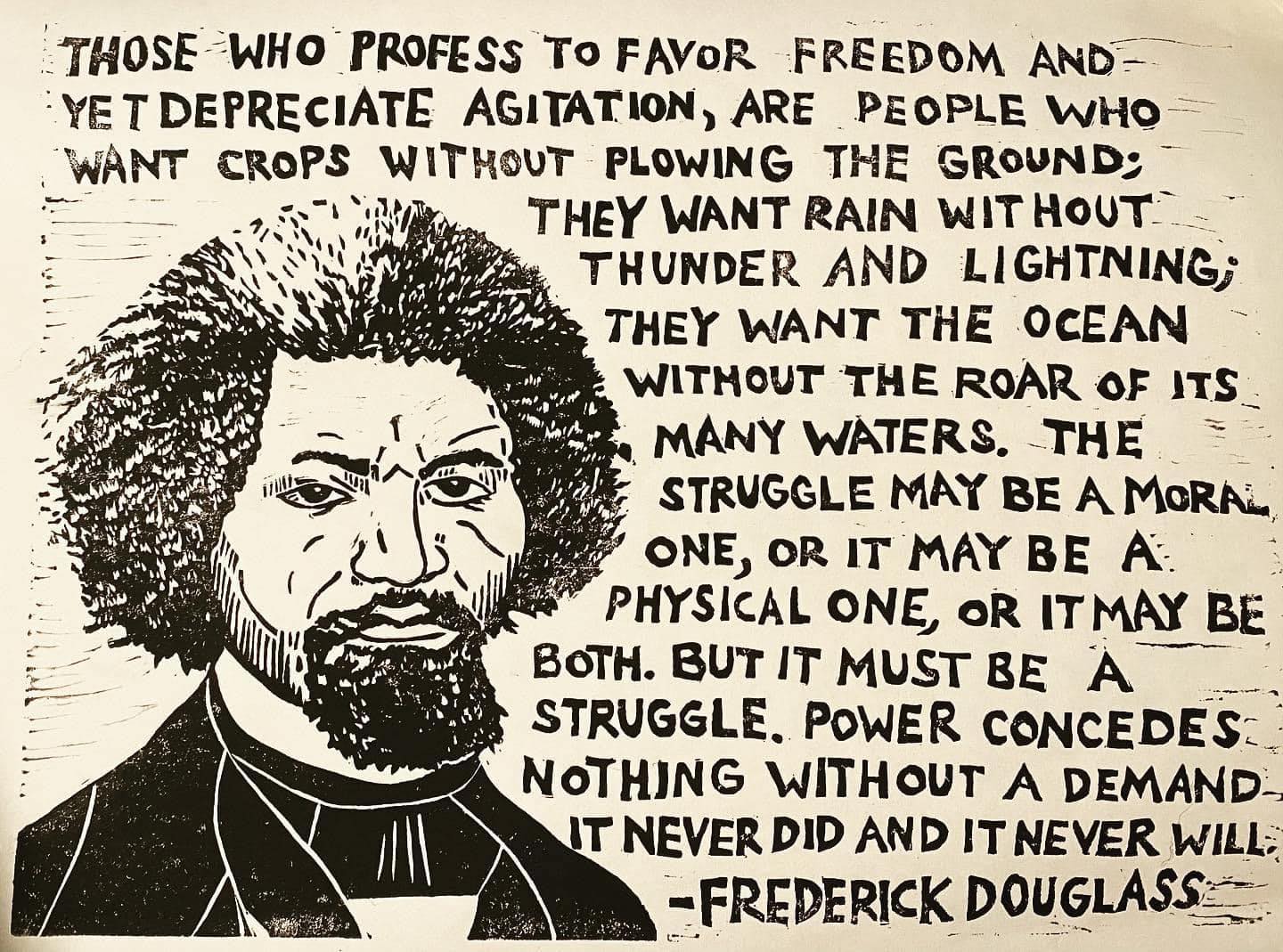

In the campaign I proposed four pillars of a thriving and healthy society. Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had proposed such pillars just before his death in 1968. He knew any new societal structure had to have strong supports to hold everything on solid footing.

Here, in summation, were the pillars: 1) clean and green environment for all; 2) social justice, including an end to mass incarceration, police killings, and discriminatory practices; 3) the end of poverty, since whenever any people are poor, no matter what that society claims, we are all “poor” in moral as well as material ways; 4) and peace in the world and peace at home.

All of this would be undergirded by a fifth pillar: a truly transparent and publicly financed corporate-free democratic electoral process. Today, elections are another industry: the 2016 national election was the most expensive until then, costing around $2 billion, while mass media made a killing on ads and commercials.

As King also stated, these pillars cannot be met under capitalism. They are contrary to a system of production and politics based on the bottom line. And all the pillars are linked. They are inseparable as we go forward; we cannot have environmental health or social justice as long as there is poverty, and no peace without environmental health and social justice…and so on.

We needed to connect the dots so as not to get divided by “my” issue over “yours.” I made the case that as a state and country we would rise or fall together on meeting the challenges of these four pillars.

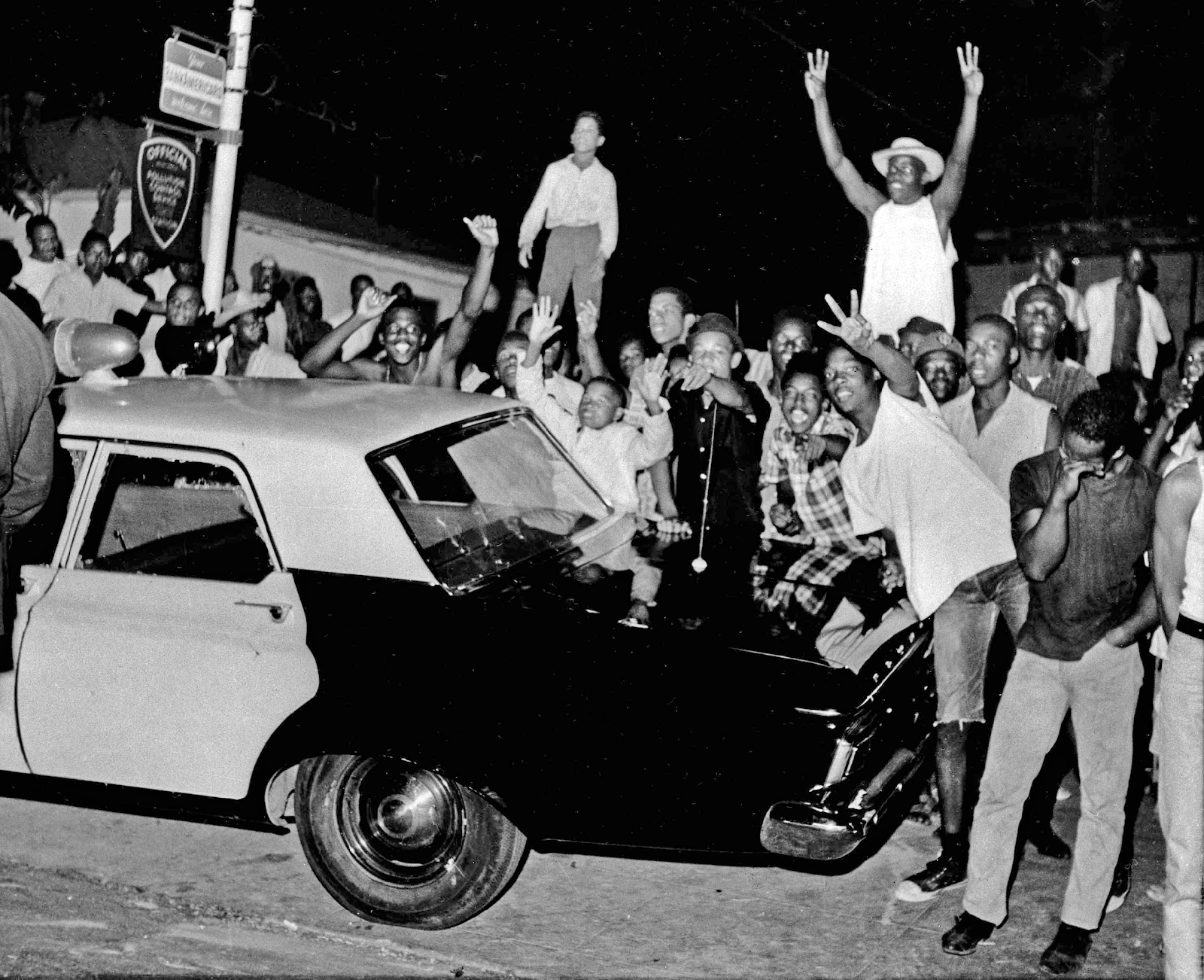

There were many highlights in the campaign. Like when I spoke at a candidates’ event at Pierce Community College in the San Fernando Valley; this school was where my father for some 15 years worked as a laboratory custodian. Also, when I marched through housing projects and streets in Watts with students, parents, and teachers for increased resources for education. I also received a great response from African American and Chicano studies classes at Fresno Community College. I spoke out against the removal of the poor and elderly from their homes in the rapidly gentrifying city of San Francisco. And I visited the largest homeless enclave between San Francisco and Los Angeles in Salinas; in addition, I marched with 4,000 people protesting the police murders of five unarmed farm workers within two years in that city.

Corazon Del Pueblo, Brooklyn & Boyle Magazine, and others from Boyle Heights organized an amazing and unique event called “The Poetry Locomotive.” We jumped on the Metro Subway from East Los Angeles, reading poetry on the trains while making various stops at stores, taco shops, and community centers. From there, community members and I read poetry and spoke on the issues. This poetry train ended at L.A.’s Union Station where a growing number of people amassed to hear poetry, speeches, and words from my wife Trini and myself.

In the end, with hardly any funds but tons of energy, ideas, and volunteers, we beat out all candidates but five with close to 70,000 votes. We were first among third party and independent candidates. In San Francisco, I finished second after Brown. And I won precincts along the Mexican border. Of course, we didn’t “win,” but we changed the larger conversation on the above issues, in particular about ending mass incarceration and seeing the end of poverty as viable and foreseeable.

We made a case that a new economic and political reality was possible.

From “Our Land to Our Land: Essays, Journeys & Imaginings of a Native Xicanx Writer” (2020: Seven Stories Press, NYC). A version of this essay appeared in “‘White’ Washing American Education: The New Culture Wars in Ethnic Studies: Volume 1: K-12,” edited by Denise M. Sandoval, Anthony J. Ratcliff, Tracy Lachica Buenavista & James R. Marin (2016: Praeger, Santa Barbara/Denver).

Luis J. Rodriguez has 16 books in all genres, including the bestselling memoir “Always Running, La Vida Loca, Gang Days in L.A.” Rodriguez is founding editor of Tia Chucha Press and co-founder of Tia Chucha’s Centro Cultural & Bookstore in Los Angeles. He has written for daily, weekly, and monthly publications and was a writer/reporter for WMAQ All-News Radio in Chicago, variously owned by CNN, Westinghouse, and NBC. As a freelance writer, he’s covered stories in Mexico, including indigenous and campesino uprisings; the Contra War in Nicaragua and Honduras; and the rise of the maras in Central America. His writings have appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, San Jose Mercury, The Guardian, Christian Science Monitor, L.A. Weekly, The Nation, Grand Street, Philadelphia Inquirer Magazine, San Francisco Chronicle, U.S. News & World Report, and The Huffington Post, among others. Luis served as Los Angeles’ official Poet Laureate from 2014 to 2016. His latest book is “From Our Land to Our Land: Essays, Journeys & Imaginings from a Native Xicanx Writer.”

Estimado Luis, fue muy emocionante leer la crónica de tu campaña. Me estimula a seguir contribuyendo, así sea solo escribiendo, por una sociedad más justa, igualitaria y democrática.