The following is a transcribed conversation between members of the University of the Poor’s History & Political Strategy Team, who facilitate studies on moments of history, in particular Lessons from the Movement to End Slavery and W.E.B. Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction in America. The members of the team present for the conversation were Kevin Kang, Ciara Taylor, John Wessel-McCoy, Phil Wider and Willie Baptist. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Kevin Kang: The conversation is centered around the theme of political polarization and political independence, and what history, particularly the movement to end slavery and the period of Reconstruction, can teach us for our current times. To start off, what can the history of the movement to end slavery and Reconstruction teach us about political independence?

John Wessel-McCoy: We use the concept of social forces to understand this history. By the eve of the Civil War, there were about 4 million enslaved black workers in the United States, in a country with a population of over 30 million people.

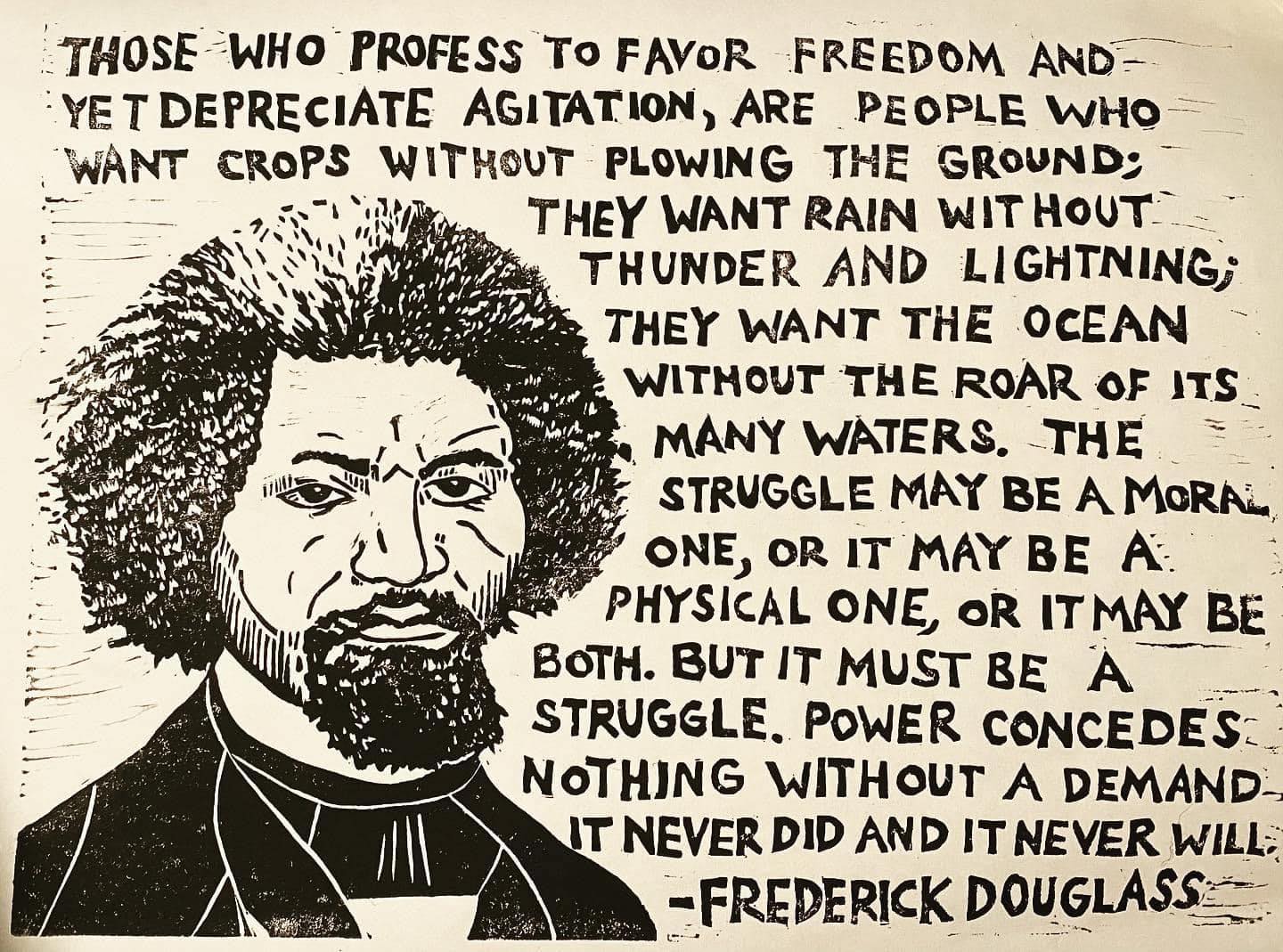

When Frederick Douglass gave his Dred Scott speech in 1857, he talked about a situation where that Supreme Court decision didn’t concern just “the weal and the woe”, or in other words not just the welfare of the 4 million enslaved black workers, but the “weal and the woe” of the entire nation. Douglass was trying to speak to this contradiction between the most powerful section of capitalists in the U.S. – the Slave Power – and the 4 million enslaved black workers held as property as chattel slaves. But also this Slave Power was in contradiction with other sections of society, whether it was the emerging wage laborers in the North, as manufacturing was growing, or farmers who were settlers in the Midwest in places like Kansas, as well as the sections of industrial capitalists in the North.

Because he had a clear lay of the land, Douglass was talking about bringing all of those who found themselves in a position of antislavery together against the slaveholders and finding a way to provide a rallying point to unite them against the Slave Power. That’s part of what we need to lift up right now. Any revolutionary worth their salt has to take stock of the lay of the land, and be clear about who’s in power and who the revolutionary social force is.

Willie Baptist: We first have to come to terms with what the basic forces at play were and what they represented? By 1857, the objective contradictions between the rising industrial economy of the North were beginning to collide with the cotton agricultural society of the South. The slave production of cotton was very rigorous and exhausted the soil. This meant that slavery’s existence required that it expand territorially and therefore the slaveholders’ land could not just be limited to the South. That was the conditioning factor that pushed events towards the direction of political independence and eventually the Civil War, and the political struggle during Reconstruction, where eventually Wall Street emerged as the ruling class of the country.

I think the social force that embodied most the contradictions in 1857 between the two economic systems of the North and the South in favor of abolishing slavery were the slaves themselves. They were the most unsettling revolutionary social force of those times. The slaves, along with the poor white homesteaders in the West who wanted Free Soil and didn’t want to return slaves back to the slaveholders, converged as forces which became the basis for political independence from the ruling slaveocracy or Slave Power and their two party system of the Democratic Party and the Whigs. They were the ones defining the terms of the independent motion, which eventually was expressed in the program of political independence, which was the non-extension of slavery into the West.

The analogy for us today is that the 140 million poor and dispossessed people objectively represent the main social and revolutionary force against Wall Street, even though consciously they’re currently scattered. And the key element here is that the abolitionists seeking the overthrow of the power of the slaveholders were involved in both the struggle of enslaved blacks and the poor white homesteaders. Through this process and positioning, they were able to pull these forces together.

JWM: There’s a lesson here in terms of how the class struggle works. It appears that there’s free soilers over here and abolitionists and the Underground Railroad over there. These social forces seem to be separate, but in fact they converge on a common enemy. And the Slave Power didn’t stand still while all of this was happening. They exerted their full might to ensure all new territories became legal slave states. Not only that, but they enacted policies to further their cause including the Fugitive Slave Act, which then created a reaction by sections of the population who had up until then been largely indifferent to the issue of slavery, but now started to get politicized because that law was an issue for them. In some ways, the Slave Power’s reactions inadvertently pushed people towards an anti-slavery position. It’s just like a fight. Someone throws a punch, and there’s a counterpunch. Over time, it draws more people into the fight.

WB: One thing we need to say very clearly is that we can’t take this history and try to apply it mechanically to our situation today. But I think the historical fact is that the whole question of political independence has to do with power. This moment in history that we’re discussing came down to the question of who was going to control the country – the Slave Power, or Wall Street, or the proletariat, as W.E.B Du Bois suggests was briefly possible during Reconstruction.

For the proletariat, the step toward political independence was separate from the existing power relationships and of the other contending forces that were fighting for power. This point needs to be considered when we’re looking at this period, because there’s this confusion about the history that tends to equate the Reconstruction period with another civil rights movement. Reconstruction importantly involved the fight of the black slaves for their civil rights but it was about a lot more than that. It was about the change over who controls state power. The defeat of reconstruction meant the rise of big capital centered in Wall Street as the new rulers. The enemy knows and learns from history and they use history to clarify their strategy and tactics. We have to do the same thing.

That’s why we study this history. We’re looking at the problems of political independence today and in history. And indeed, in the past, the move toward independence by the poor and dispossessed was independent from those in power. In this case, the abolition movement was not only defeating the Slave Power, but raising the question of whether the proletariat was going to be able to take power. So independent politics at that moment was independent largely of the Slave Power, and because they were able to accomplish that independence they succeeded in overthrowing the Slave Power and implementing a whole new power relationship in the country. That was what Reconstruction was about. It wasn’t just civil rights legislation.

Phil Wider: The history of the enslaved black workers teaches us how up to a certain point they took advantage of conflict between different sections of the ruling class and led other social forces to free themselves. But at another point, they were instrumentalized. We can also see that in this history leading up to the Civil War and the period of Reconstruction there were two revolutions – to defeat the Slave Power and then to defeat the Money Power (Wall Street). The first revolution was successful because there was actual organization to defeat the Slave Power. But the second revolution wasn’t because there was not organization to defeat the Money Power.

As John alluded to earlier, some of the prevailing conceptions of this history that separate out the various social forces (such as free soilers, northern workers, abolitionists, free black people, enslaved black workers and the Underground Railroad) end up promoting a siloed, syndicalist, Alinsky-style of organizing that obscures the kind of political organizing needed to build the unity and political independence of the poor and dispossessed as a social force. For decades, we have been talking about a movement to end poverty led by the poor as a united social force across lines of division.

But sometimes I feel that this formulation goes in one ear and out the other. People will think “yeah, I understand, we’re fighting for housing, we’re fighting against ICE, etc.”, but there’s something deep about this formulation of a movement to end poverty led by the poor as a unified social force that has to be appreciated. We’re using these scattered fights to pan for gold (leaders) and unite these leaders to fight for the unity, political independence, and leadership of the 140 million poor people in this country. Only if we come together as a unified social force will we be able to lead a broader movement to transform society.

KK: Can someone say a few words on the emergence of the Republican Party and its significance in developing the motion for political independence?

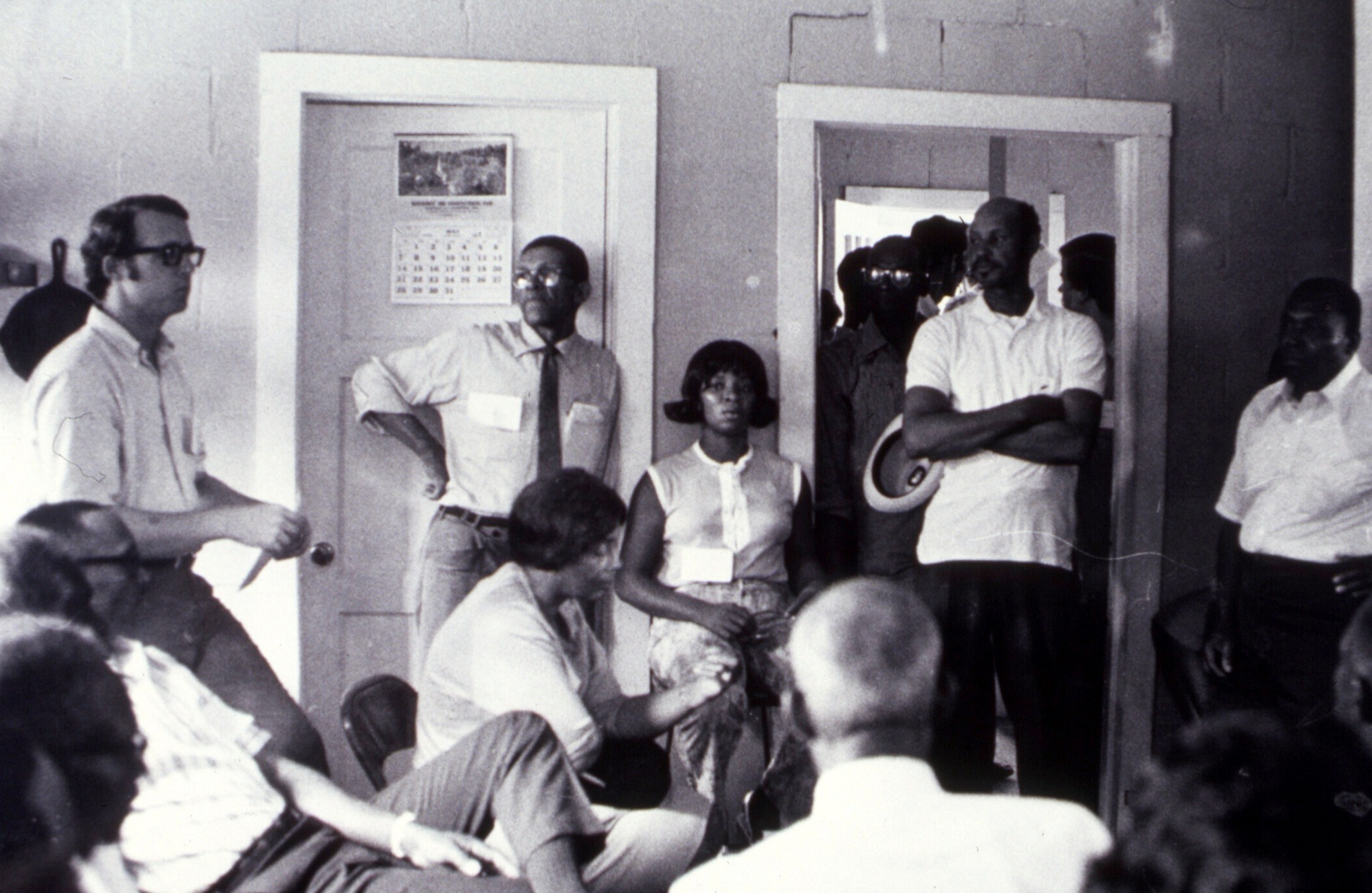

JWM: In terms of the emergence of the Republican Party, the origins of the party are rooted particularly in Bleeding Kansas during the 1850s. The party didn’t emerge from some disconnected folks who wanted to start a political party. It actually emerged in a very organic way, tightly connected to the motion of sections of the working-class in response to the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 and the events surrounding Bleeding Kansas, when people were battling over the future of slavery in that territory. Bleeding Kansas really gave birth to the Republican Party and consolidated people into the party. The fact that it first emerged in the form of these small organizing committees in little towns in Wisconsin, Michigan and so on, which really start off as relief societies to aid the free soilers in Kansas, is quite significant. That becomes the real base of the Republican Party. If parties are an expression of classes in conflict, here you have the emergence of new potential independent forces.

WB: The whole struggle of Bleeding Kansas, to have that territory come in as a free state, was a very important moment in the struggle against slavery and for political independence. That’s where you had the struggles of the slaves through the Underground Railroad objectively coming together with the struggles of the free soilers, particularly the poor whites. It was also when these relief committees were formed throughout the North to support that struggle.

Those committees, along with previous efforts by abolitionists to form an independent party, first as the Liberty Party and then the Free Soil Party, eventually constitute the origins of the Republican Party as an alternative to the existing two party system with the Democrats and Whigs. The Republican Party pulled together all of those elements that were polarized on the side of anti-slavery, along with the relief committees, temperance societies, and other institutions that were all basically siding against the slave autocracy’s aim of extending slavery into the West.

KK: How do we see these political polarizations playing out and how do the abolitionists take advantage of them?

JWM: The 1850s was one major incident happening right after another. The tempo was really picking up and we can’t talk about the rise of the Republican Party disconnected from the Fugitive Slave Act and incidents like the Christiana Riot in Pennsylvania in 1851, where freed and escaped folks, as well as white abolitionists, forcibly resisted the capture of fugitive enslaved people. You also have the publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852.

We’ve been talking about “Bleeding Kansas”. At the same time, outright abolitionists were getting elected into Congress throughout this period and becoming very vocal. And it just goes on. There was the Dred Scott decision in 1857 and then John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859. So it’s just one thing popping off after another, and abolitionists were playing this agitating role where they weren’t just taking advantage of the polarizations. They were actually contributing to the country’s move towards further polarization on the question of slavery.

WB: The significance of polarizations is that they can be used by the enemy to further divide, or we can identify those poles that can be united within the polarity. Deep polarization can really break up the existing status quo, which is a certain unity among the enemy, like when the army starts splitting and when the churches start splitting during this historical period. When the Whigs collapsed, and then later when the Democratic Party split, new opportunities opened for the abolitionists to go forward in their education and agitational roles to pull and push society towards an anti-slavery position. During the war, they were able to make the struggle about ending slavery, and not just keeping the Confederates in the Union. This allowed them to win Lincoln and all these people over to the fact that the bottom line was slavery.

So the focus of the abolitionists was on every section of society. They were in a position to really pull things together when, finally, the rest of society during the midst of the Civil War came to understand that the defining issue was slavery and that it was more than a constitutional crisis. Because of their positioning in all these motions, they were able to exert their influence. And that influence was predicated on grabbing a hold of and uniting the poor white homesteaders and slaves who together represented the position of abolition.

Building this influence was a long term struggle. Much earlier, there is the involvement of the more conscious Abolitionists with the slaves, particularly in assisting the development of the Underground Railroad as it evolved from various scattered but persistent attempts of runaway slaves in the 1700s all the way to the more organized Underground Railroad by the time Harriet Tubman became its lead conductor in the 1850s. By the 1840s and 1850s, the Underground Railroad became a major force of ideological and political influence in the country. In fact, the whole struggle over the non-extension of slavery had to do with not having the territories, especially Kansas and Missouri, come in as slave states, but as a free states.

JWM: During these polarizations, the abolitionists were credited with naming the enemy as the “Slave Power,” this tiny minority that had so much economic power. The abolitionists agitated to get people to name and understand that whether they were a farmer or a fugitive slave, the Slave Power was the force that they were up against. The Republicans from the very beginning when they emerged in the 1850’s adopted that language and used it very clearly.

Ciara Taylor: Right now, all of us are caught up in the chaos of today’s polarizations, but not truly understanding the forces at play. Without understanding these forces, the working-class will be used as pawns to consolidate the ruling class’s power. What is our role as revolutionaries to move the working-class to political independence? Knowing that we are primarily speaking through this article towards UPoor members, are there any direct words we want to impart to them?

PW: For me, the question that stretches across all of this is how the revolutionary forces establish their political independence and lead other social forces to secure their interests. I think that happens across the various stages of this process of the movement to end slavery, through the Civil War and into Reconstruction. Political independence didn’t start with the election of Lincoln. It had already begun prior and then entered the electoral arena, first through the Liberty Party and Free Soil Party, and then finally with the Republican Party. The coalition of forces that was involved in each of those party formations grew as a result of growing polarization and an evolving political program that expressed that alignment of forces. I think John’s point earlier on this question of the Slave Power is important. The forces that came together didn’t unite around ending slavery. Subjectively, they united against the Slave Power, which they were objectively in opposition to.

A significant composition of abolitionists came from the ranks of the leading revolutionary force, which was the enslaved black worker. The northern worker and the western farmer were also in the ranks of the abolitionist cadre. So there’s something here about the relationship between the cadres and the revolutionary force and its activity. I really like how Willie talks about how this activity moved from slave uprisings to the Underground Railroad to the general strike of enslaved people during the Civil War to the election of black officials in Reconstruction. There was an evolution in the forms of struggle through which that leading force rallied and moved other social forces.

The thing that strikes me is that there were cadre in relationship to the enslaved masses and its forms of struggle that were able to take advantage of the contradictions, secure the abolition of slavery and the confiscation of the dominant form of property, and cause a major economic and political realignment. However, there were not sufficient cadre that could sustain that objective unity against the Slave Power and move it into a unity against the Money Power that was emerging through Wall Street after the Civil War.

WB: There is a lot from this history that can instruct us today. The abolitionists, as cadre taking up a clear understanding early on of the Slave Power and the abolition of slavery, were able to pull together these separate responses to the different policies of the slaveocracy. The Slave Power had a policy around race, the role of women, foreign policy, the military, and so on. They had all these different policies. And it was the constant agitation of the abolitionists that successfully connected all of these policies back to the slavocracy.

The main positive lesson here for our survival struggles today is that we must focus strategically on the actual organization of that section of society that has the least ties to capital. Those who are the most oppressed and exploited by capital. Building that organization is the only basis of real independent politics of Wall Street, the ruling class. In the historical case of the struggle against the Slave Power, we must understand how the Abolitionists were able to strategically concentrate and connect all their energies and efforts to uniting and organizing slaves, in terms of the Underground Railroad, with the poor white homesteaders in terms of the Free Soil movement. The Abolitionists eventually played an indispensable role in bringing the slaveocracy down from power and abolishing slavery.

Kevin Kang is a member of the University of the Poor and the Popular Education Project, and comes out of experiences in immigrant rights struggles.

John Wessel-McCoy is a member of the University of the Poor History and Political Strategy Team, and is based in Phoenix, AZ.

Ciara Taylor is a member of the University of the Poor, the Popular Education Project, the National Welfare Rights Union and the National Union of the Homeless. She works with CODEPINK as the Director of Cultural Strategies and rocks out with Subversive Activities.

Willie Baptist is a member of the University of the Poor, Senior Advisor of the National Union of the Homeless, and Executive Board Member of National Welfare Rights Union.

Phil Wider has been an organizer and political educator in the U.S. movement to end poverty for over three decades. His entry point to the U.S. survival movement was through the Philadelphia/Delaware Valley Union of the Homeless, a lead chapter of the National Union of the Homeless. He’s currently a Co-Coordinator of Political Education and Leadership Development with Put People First! PA, a member of the Popular Education Project and a Co-Coordinator of the University of the Poor’s Political Coordination Committee and Standing Committee.