by Rev. Tonny Algood

In presenting this issue of the University of the Poor Journal, we consider the possibilities and challenges for political independence of the poor and dispossessed in the U.S. In his piece, Dan Jones affirms that the movement for political independence of the poor and dispossessed has “always faced its greatest obstacles in the U.S. South and in particular the Black Belt, the home soil of the ideology of all-white all-class unity…The central battleground for the political independence of our class is in the South today.”

Current struggles to organize the poor and dispossessed in the South, such as the fight by Amazon workers to organize in Bessemer, Alabama, can learn from earlier experiences of organizing across color lines. Here we interview lifelong organizer Rev. Tonny Algood. He is a member of the University of the Poor, the Freedom Church of the Poor, and a Tri-Chair for the Alabama Poor People’s Campaign. He works with Fed-Up Mobile, and sits on the executive committee for the NAACP and the boards of the North Alabama School of Organizers and the National Union of the Homeless. In this interview, he describes organizing pulpwood haulers in Laurel, Mississippi in the 1970s. This struggle exemplifies the fusion politics that we believe is required to challenge the ruling class politics of divide and rule and to forge the possibility for another independent politics led by the poor and dispossessed.

This piece combines an interview of Rev. Tonny Algood by Peter Kinoy in 2015 with an interview by Alicia Swords in April 2021. When possible, we have provided links to biographical information for people mentioned in the interview.

Peter Kinoy: After the summer of 1970, when you graduated from Millsaps, how did you end up with Project GROW (Grassroots Organizing Work)?

Rev. Tonny Algood: Well, during my senior year I had worked with some folks from the Voter Education Project Southern Regional Council. I set up internships at Millsaps, was involved in other things, and when I graduated, based on the work and the connections I had made in the summer of ‘70 — John Lewis was the head of the Voter Education Project in Atlanta and Charles Evers was mayor of Fayette, Mississippi — they hired me and two other students who were Black, one from Millsaps and a friend of mine, to set up a speaking tour for John Lewis and Julian Bond in north Mississippi and south Mississippi for voter registration.

Charles Evers was going to be running for governor and that was the way to build enough support. So that’s what I did that summer and got to meet fantastic people. Fannie Lou Hamer, E.W. Steptoe, and other old civil rights workers, just all throughout Mississippi, and then got to travel and meet work with John Lewis and Julian Bond and Charles Evers.

Well, when we had completed that job [the Voter Education Project], the Greater Jackson Area Committee had applied for a grant [for a project called] Informed Mississippians for Greater Public Education. The way to support education was to get Blacks and whites organized together and working together. So it was working with Black and white pulpwood haulers in Mississippi and the GROW Project (Grassroots Organizing Work). That was organized under the Southern Conference Education Fund (SCEF) when Anne Braden and Carl Braden were the directors. Bob Zellner, former SNCC worker out of New Orleans, was part of that. And so I moved to Laurel, Mississippi and was there in September ‘71 when a strike broke out with the pulpwood haulers in Laurel.

PK: Wow, so we were in 1971-72. You’ve started with the pulp workers up there in Laurel, Mississippi.

TA: I was working in Laurel, Mississippi. I was living there, of course we were organizing pulpwood haulers in south Alabama, north Alabama and south Mississippi. That was where the heavy concentration of the paper industry was, and so here I am living in Laurel. And had just moved down there, maybe about four weeks, and the woodcutters just there in Laurel go on strike against Masonite. It was just kind of a wildcat spontaneous strike.

Now, Bob Zellner and Steve Martin and Marie Daniels and all them had been organizing the pulpwood haulers for about a year and organizing Black and white wood haulers. So, as it turned out, Laurel became the headquarters for the pulpwood front. We were trying to get supported everywhere that we could. The white woodcutters had said, “well, let’s go see what kind of support we can get from Bill Waller,” who was running for Governor. And I thought to myself, there’s no way on God’s green earth that he is going to support the pulpwood haulers. But let them try. And of course they went, and he turned them down.

And having worked with Charles Evers, I said, “well, let’s go contact Charles Evers, and see if he would support us.” And we went up there with the delegation and we sat down and we talked with Charles and he said, “sure, sure, I’ll support this. This is a poor people’s issue and it doesn’t matter whether it’s Black and white or whatever. So we’ll support it in our campaign.”

See, what we were trying to do was to get the state to adopt a standard measurement for pulpwood. Then it was being sold by the unit, which could be anything that the wood dealer wanted. But a cord was a set measurement, 7 by 7 by 8. [The workers needed] a standard measurement so they wouldn’t be cheated.

And so Charles Evers wanted to come down to speak. He was going to speak at the Jones County courthouse. Now one thing that you need to understand about Jones County, it was the heart of Klan territory. Very strong Klan movement in Jones County. And so particularly whites had been exposed to all of that. Bob Zellner and Walter Collins and all of them had gone a long way in breaking down some of those barriers with the white workers at Masonite Corporation when they went on strike in 1967. And he still knew some of the Masonite workers at that time.

So here Charles Evers is coming down. The day before he is supposed to speak, the Laurel Leader called. Comes out with an editorial in the newspaper. It had a stack of pulpwood and it had published — written right across it and underneath it — a picture of a hammer and sickle and the caption of it was, “At the bottom of all this.” It was a two-column-long editorial and it was red-baiting the strike.

Charles Evers shows up, and he comes to my apartment where we met before going down to the courthouse. And he wants to know, “What’s all this we’re hearing in the paper and all over the county?” And Bob said, “They can’t race-bait us, because we are working together and it’s poor Blacks and poor whites, so they are trying to use this. That’s not the issue. The issue is people receiving a livable pay for their work and not being exploited. Poor people just trying to put food on the table.”

I looked out and there was a Masonite car parked out front with one of their security guards. And one of Charles’ security men said, “I wonder if he has a gun.” I said, “well, he probably does, but he knows y’all have them, too, so it shouldn’t be any problem.” [After that], we went down there to speak, not knowing how many were going to show up after seeing that article in the paper.

But the place was packed. It was standing room only, Black and white. And Bob Zellner got up and spoke, then Charles Evers got up and spoke. And there was this huge round of applause, and he placed his support and [said he would] get the support of the NAACP for the strikers.

The next morning, I got evicted because of them coming over to my house. And then I moved into another house, and stayed there for about a week and got evicted from there. I thought, it’s going to be hard to find a place to stay in this town.

We found one house that was an old dairy barn that had been converted into living quarters. Rooms upstairs and downstairs where the dairy barn was. It was a kitchen and a little room and we used that for the office. It was owned by a former worker, a white worker at Masonite who had been injured at Masonite and gotten the shaft. He hated Masonite worse than the Lord hated sin. He would talk about George Wallace and the Klan coming and having rallies in his backyard. And we said, look, “we gonna tell you, we are organizing everybody, Black and white.” He said, “If it’s against Masonite, that’s fine.” So we stayed there forever. That was our headquarters.

Then Charles Evers goes back and he gets the support of the NAACP. They came down and they are writing thirty-dollar checks for each striker and their family a week, for strike benefits. And that was a lot of money back then.

PK: The NAACP was doing that? Was it national or was it local?

TA: It was national. The National NAACP was writing thirty-dollar checks to the strikers. And that thirty dollars was an awful lot. I saw white woodcutters and I have been to their homes. Their homes were shacks. Some of them didn’t even have indoor plumbing. I saw them take their checks, endorse them, cash them, and go pay their dues to join the NAACP. So we had the white woodcutters join the NAACP. And not only that, they were supporting Charles Evers for Governor, which was incredible, especially during that time.

PK: What would you say that you’ve learned over the years that might be important in a rebuilding of a Poor People’s Campaign?

TA: Now one thing that I see, there are a lot of individual struggles happening all over this country… where the people are fighting for healthcare through Medicaid expansion, or people fighting for sanitary conditions in rural areas with the sewage at their houses and all, or people not being able to pay their light bills, and we could go on and on. We have all these individual struggles…[with] very good, hard-working people, and really across the political spectrum. Democrats or Republicans. They may vote Republican, but they are out here struggling for education, or whatever…

There’s going to have to be a movement organization that’s going to be able to take in and encompass and be the umbrella for all these individual struggles, and to be able to connect them in a political force, so that we can have housing, and food and healthcare and quality education and a system that will take care of our senior citizens. And it has to be that kind of unity. This can’t be done without the organization taking place on local levels, but those local struggles are going to have to be united and linked up.

Alicia Swords: How would you connect this experience of organizing the pulpwood workers with the need for the political independence of our class?

TA: If by independence, we mean a certain section of the class turning away from the politics that they were following to move in the direction of supporting candidates that openly come out in support of their needs, I believe this was done when the poor white workers who had been supporting the reactionary Mississippi white politicians came out and voted for and supported Charles Evers for governor because he was supporting them in a very, very real way. Now that was a huge break…

But it’s clear too that there is going to have to be more than just a Democratic Party or a Republican Party to really and truly represent the interests of workers, of people who have been oppressed because they’re minorities, and a system that is creating every day more and more homeless and permanently unemployed by replacing them with robots and computers and artificial intelligence and all.

It was a fellow Alabamian, Helen Keller, who said when you vote for a Democrat or Republican it’s like voting for Tweedledee or Tweedledum who want to represent the interests of the rich. And that is so true, and this is part of the education process. Some of the best education is done when people are going through a struggle, just like the pulpwood haulers.

Let me say another thing that I found out in my history of working in the Labor Movement is that other than the reactionary plantation politicians who claim they represented the interest of the poor whites, no one ever organized them as a group, like Black folks were during the Civil Rights Movement.

And what I have seen, and this was one of the things that was so clear about the pulpwood strike, was that the white pulpwood haulers would automatically assume that the white politicians that were running for governor were going to help them, like Bill Waller, and he slammed the door in their face. And then when help was offered by Charles Evers in his campaign, that changed their whole outlook on things. It was very, very powerful. When you had white woodcutters — some of them had been members of the Klan — take their $30 benefit check from the NAACP that they received each week and cash it and turn around and pay their dues to join the NAACP, and then campaign for Charles Evers. That’s big, you know, that’s important.

When we talk about political independence, one of the first steps is poor whites, poor Blacks, Latinos, Asians, poor people of color, all people, coming together and setting forth the policies that they want to see passed, the changes they want to see made, and not really to placate either the Democrats or the Republicans. I mean, how many times do people go to the polls and say I voted for the lesser of two evils. So you don’t want to be beholden to Tweedledee or Tweedledum.

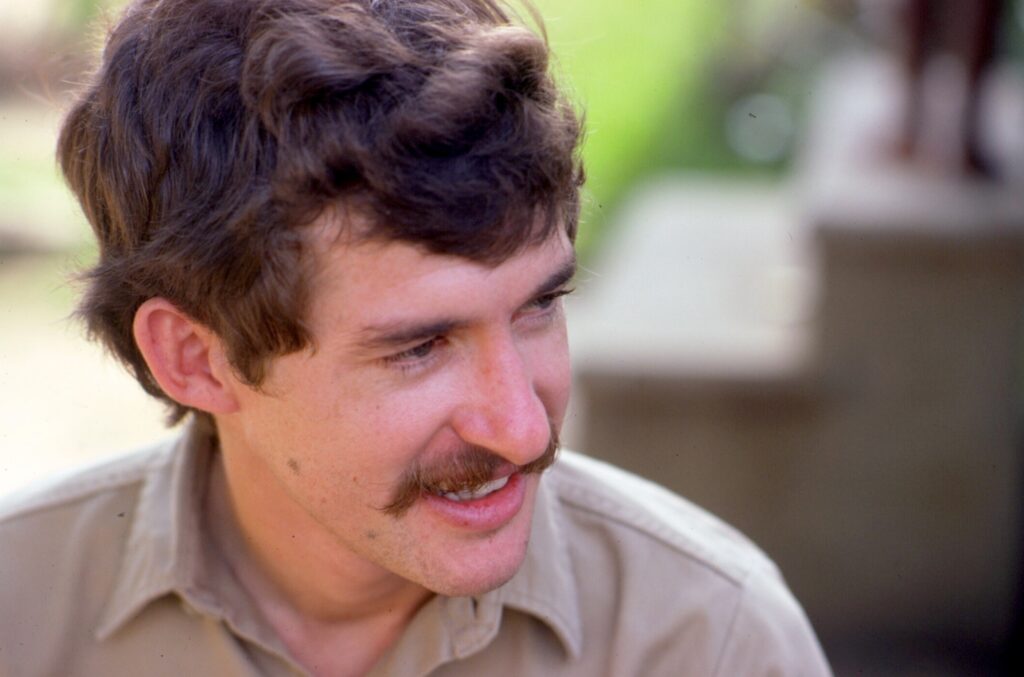

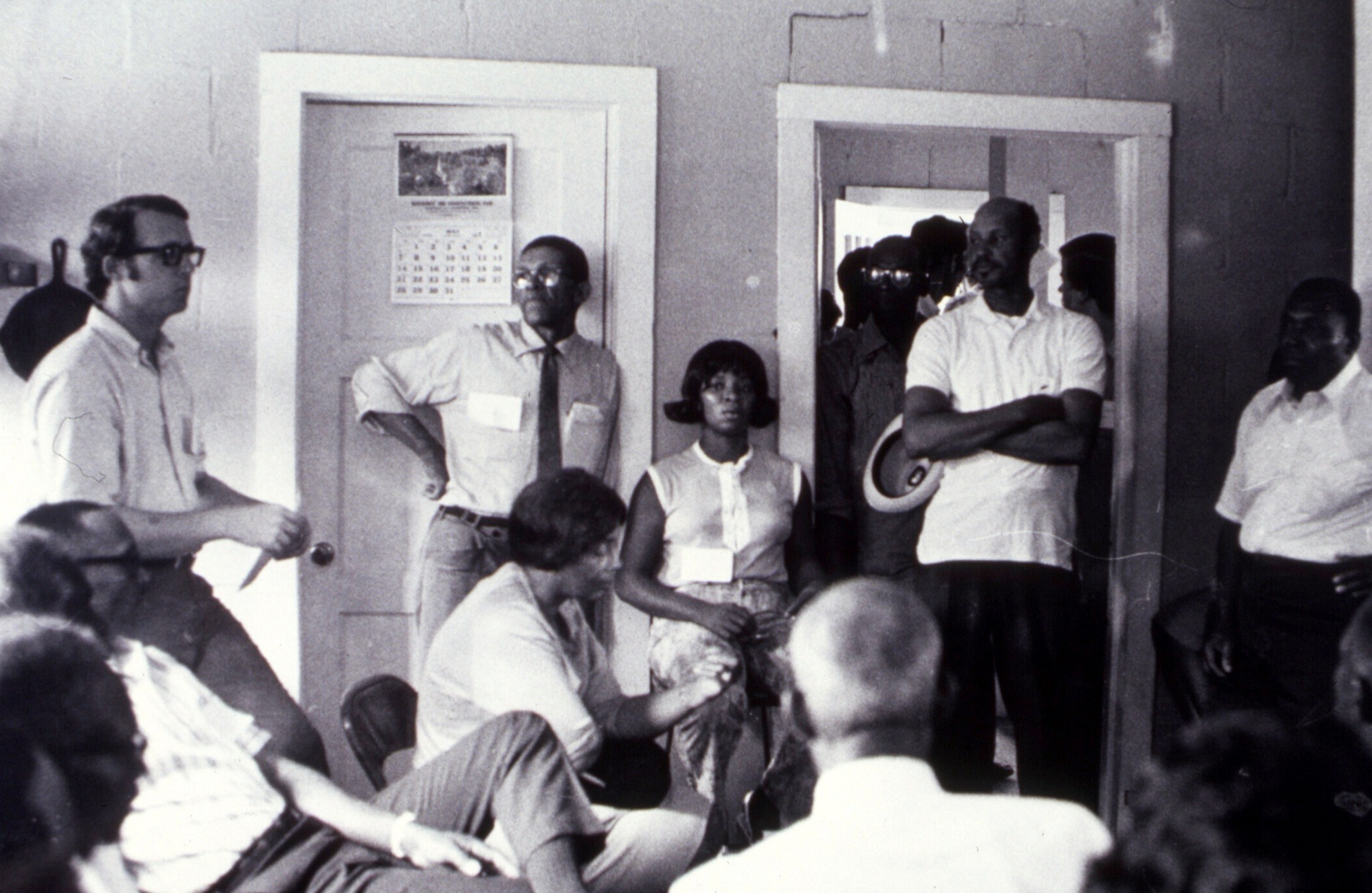

*Featured photo: Local meeting of the Gulfcoast Pulpwood Association in Newton, Mississippi during the strike of 1971, credit Louis Marcelli.

Wonderful interviews. Long live Tonny!