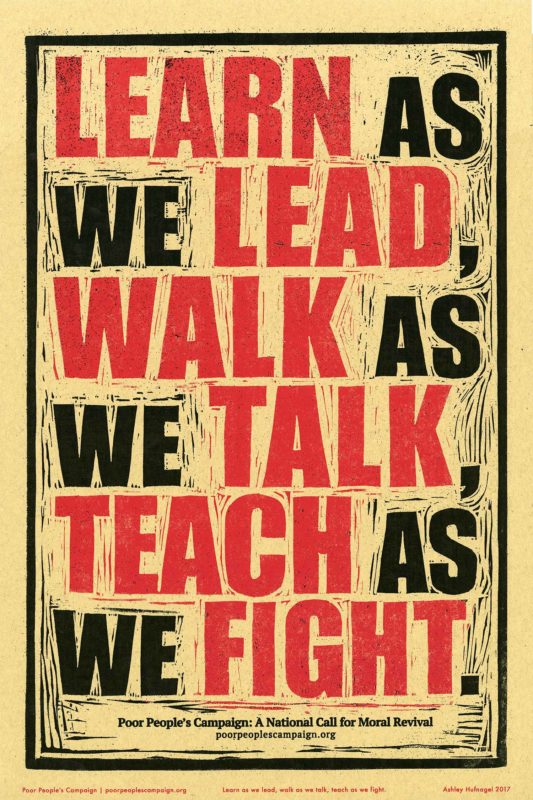

Tim W. Shenk, for the University of the Poor Journal: In this inaugural issue of the University of the Poor Journal, we’re focusing on the political independence of our class. We know that we can’t just announce that we want to be politically independent of the formations of the ruling class. We have to build that independence, and that comes with developing leaders who can navigate difficult and ever-changing terrain. Charon, you’re a leader in the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival. You’re part of the Kairos Center and University of the Poor. These are some significant efforts to develop leaders in the fight to end poverty. How do you think about leadership development as part of building political independence?

Charon Hribar: These are great questions. Let me start with where I come from. I grew up in western Pennsylvania in a steel town called Aliquippa, just north of Pittsburgh. I was a child of the ’80s, which was the time when the steel mills were closing. As a kid I saw family members and neighbors losing their jobs and saw the stress that put on the whole community. We also had so many people dying young. Looking back, you put two and two together.

We had the first nuclear power plant in the country near where I grew up, in Shippingport. We had a uranium plant where my grandfather worked, where they were enriching uranium during World War II. My grandfather died of a brain tumor at 57. They didn’t even start to clean up that plant until the ’80s. There was a lot of environmental contamination in the area. I had a lot of family members who got cancer and other autoimmune diseases, and so many people died way too young because of where they lived and where they worked. That was part of the invisible war on the poor. But I don’t know that I fully appreciated that while I was living there.

My parents didn’t go to college, but my mom always wanted me to go. I ended up going to college in Erie, Pennsylvania, to a Catholic college that had a strong liberation theology faculty. And that was really the start of what politicized me to start thinking about how religion should respond to the problems of the world. I went to Peru with a Jesuit priest after I graduated from college and had a chance to meet and work with Christian base communities there. I was able to see an approach to doing that work that was steeped in an understanding of the economy, of globalization, and the history of Peru and its civil war. They wanted to figure out, from a faith perspective, how to be serious about getting to the root of the violence and poverty there.

When I got to Union Theological Seminary [in New York City] in 2004, some of the first people I met were Willie Baptist, Liz Theoharis and Ronald Casanova. They were coming out of years of work in the National Union of the Homeless and in the Poor People’s Economic Human Rights Campaign. The Poverty Initiative being founded at Union that year was a chance for them to regroup and commit to our mission of “raising up generations of religious and community leaders dedicated to building a broad social movement to end poverty, led by the poor.” There had been a lot of activity, but there was some real unworkability with the organizational forms.

That was the space I was coming into, where the founders of the Poverty Initiative knew they needed to start a rigorous process for leadership development and political education. I think this is one of the pieces of leadership development: knowing that it’s not always the organizations that will last. Organizations may come and go, but it’s the leaders who are developed through those processes who can be decisive in knowing when something new has to be built. Leaders are people who can maneuver and move past challenges that may arise, because it comes down to being able to continue to do the work of uniting our class and raising up the kind of leadership that’s necessary to do that.

One of the exercises we used to do in the Poverty Initiative, and still do, is called poverty mapping. This is where we invite people to look at their own journey and how the issues of poverty and systemic racism intersect with our lives. We often did poverty mapping on immersion courses through the Poverty Initiative. Those immersion courses were powerful moments where we would go to different places around the country, like Appalachia, New Orleans, rural New York state, and meet with leaders organizing there. Along with that, we had time to reflect and share our own stories.

I remember being on an immersion trip with Nijmie Dzurinko. We had both grown up in western Pennsylvania. Both of us got to share what that looked like, seeing the deindustrialization of where we grew up and the impact that had on our families. Hearing her was like seeing myself, in many ways. Of course our stories had differences, including the role of systemic racism, but there were many common threads. I remember how important it was to recognize that the hardships my family was facing weren’t because of their own fault. That really, there was something larger going on.

Seeing different communities all over the country and hearing people’s stories really helped me to recognize the social problem we were facing. I think it really gets to this quotation from Dr. King, when he says, “The only true revolutionary, people say, is a man who has nothing to lose. There are millions of poor people in this country who have very little, or even nothing, to lose. If they can be helped to take action together, they will do so with a freedom and a power that will be a new and unsettling force in our complacent national life.”

Getting people to the point of seeing that we have nothing to lose in a system that continues to kill our people, and we have no stake in preserving that system — that’s really what developing leaders, developing cadre, in this movement is about.

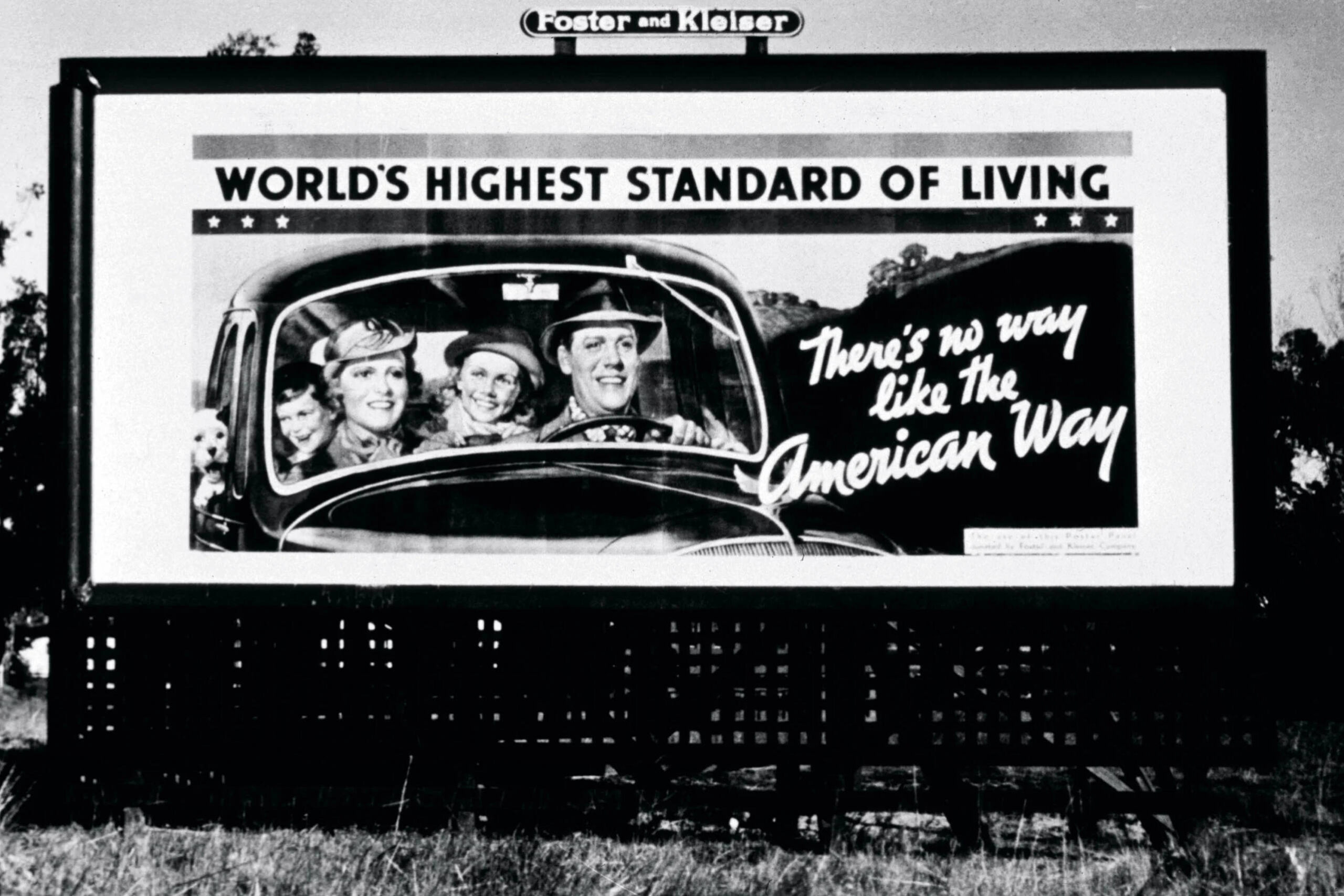

A lot of people in our society are stuck thinking, “Well, this is the best system we have. And we just have to deal with it.” So we need to help them move past that and recognize that there’s tremendous wealth generated in this society, and that a majority of us are kept from it. At the same time we are fed a narrative of scarcity — and we need to develop a counter narrative that asserts that we have no stake in supporting a system that does this to us.

TS: Going back to the poverty immersion courses for a minute, it sounds like there were a lot of elements at play. These trips were part of identifying weak points of the system and its narrative by going places where the system was failing people in particular ways. And the connections helped to build a national network that would emerge as the new Poor People’s Campaign. A third part, then, was about the people on the immersions who were growing into new consciousness and growing together through these experiences.

CH: Yes. This makes me think about stages of a movement. In the early years of the Poverty Initiative, it was really clear we couldn’t do something as big as a Poor People’s Campaign until we had developed and united leaders around the country. That has to be one of the first stages of a movement. Uniting leaders on the basis of what they have in common as well as a shared mission, which is uniting the poor and dispossessed across all of these different lines of division. We were doing these exchanges, these immersion courses and strategic dialogues, but it was really planting seeds for the stage we’re in now. We’ve been able to launch the Poor People’s Campaign in a moment when we’ve started to see the legitimacy of the system break down.

It takes real cadre to recognize an opportunity where the system is weak, and be able to move and mobilize people from among the 140 million poor and low-income people in this country who are hurting the worst at this moment. We need cadre — folks who have these deep relationships and deep understanding — to help hold out a way forward, in times when masses of people are going to be forced into motion because of their conditions.

TS: I appreciate that. Can you say more about this 15-year build of the Poverty Initiative and Kairos Center, and its role in the ability to make the leap to a national campaign?

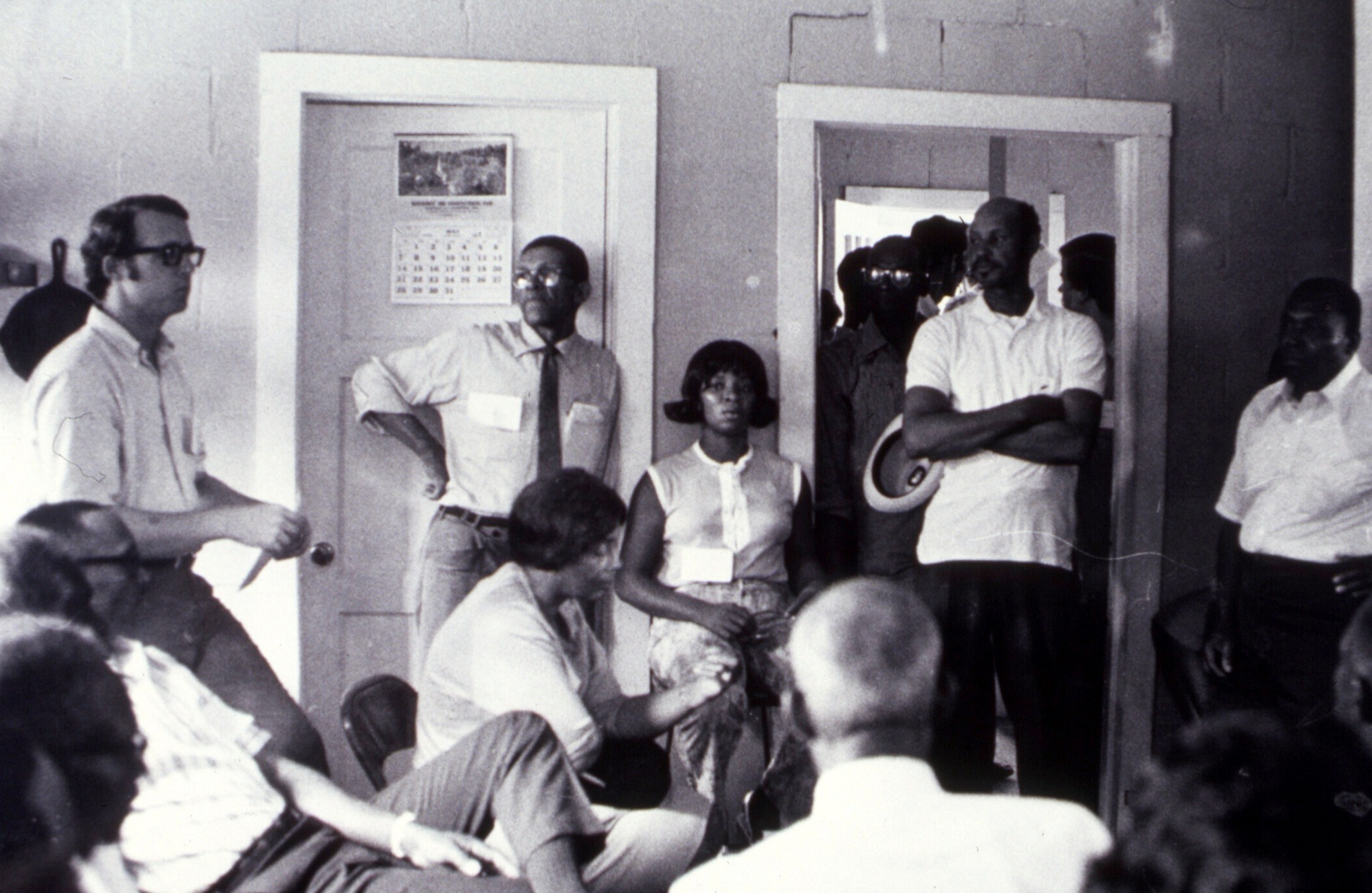

CH: I can say a few words about the Poverty Scholars Program’s strategic dialogues and leadership schools. They were ways to start to develop leaders and think about what it was going to take to build that necessary unity of our class. We brought leaders from places like Detroit, Appalachia, Philadelphia and other places around the country. We were able to have them in conversation with powerful leaders from organizations like Abahlali baseMjondolo, the shackdwellers movement of South Africa, to start to develop a shared analysis of what was going on. Who are we up against, and what was it going to take to actually build something to address the problem at hand?

The dialogues were a way to analyze the current moment and the shifting economic and political situations. We would have economic crisis presentations — this was during and after the 2008 crisis — and pair the macro-level understanding with the experience of our leaders on the ground in local communities fighting against the daily realities of water shutoffs, housing evictions, low-wage work, a lack of access to healthcare and more. How does that help us to better clarify the conditions? We know oppressors will not oppress every group in the same way. How does that, then, fit into what it means to unite the poor and dispossessed?

That process really helped strengthen and build leaders who are leading the movement today, as well as new organizations of the poor and dispossessed. We saw Put People First! PA emerge from these experiences of the Poverty Scholars Program, learning from the successes and failures of other organizations that came before them.

A big part of building unity is building real relationships, which also came out of these strategic dialogues and leadership schools. I would dare to say that these real relationships are a big part of what’s keeping the Poor People’s Campaign growing today. When we got to go to Aberdeen, Washington or Lowndes County, Alabama, we got to really be in community with each other. We weren’t just getting together in some sterile conference room somewhere. Being on the ground was so key to understanding people’s conditions, feeling the power of their stories, and knowing we would do everything in our power to fight for one another.

TS: We say that movements begin with the telling of untold stories. Can you expand on what you just said about the power of stories and the relationships that are built around our stories?

CH: Sure. Developing leadership among the poor and dispossessed is partly about not being ashamed of the reality of poverty. We share through our own stories and experiences that there is a system producing the conditions we’re facing, which frees us to notice that we don’t have anything to lose.

People are surprised when they actually see these relationships, and how our leaders are “in step” despite all of the potential divisions of race, geography and everything else. We’ve had people tell us, “Oh, I thought that was just something you say, that you have people coming together across different racial and religious lines and so on. But this is actually real!” They’re surprised, because most so-called coalitions don’t work that way. We know how long we’ve been building this. We have studied history and understand how these divisions have been sown. We know how important these relationships are, because it’s about needing to hold together while organizing against a system that wants to keep us divided.

Another aspect of this is what we call the mental terrain. How are people responding to the conditions with which they are faced? In 2008 we had a major economic recession, and you would think, “Why isn’t everyone coming out and responding? Why doesn’t everyone recognize what’s happening here?” Those in power are really good at masking why things happen and keeping us at odds.

So a lot of the work we’ve done in these spaces is to unpack and understand the mental terrain, and the role that religion and race have played in this country to maintain the power structure as it is. It’s deep to get people from different communities and backgrounds to understand that so we’re not continuing to fight each other. This network has fought hard to understand how we’re all being impacted by the conditions. We’re starting to be able to counter the dominant narratives that have propped up a society that is so desperately unequal. Learning history, and being able to understand the economy, are always part of our curriculum, because we’ve been so misled by our education in society in that regard. Putting that next to narrative storytelling has been a key. Being able to understand the economy and history, and then being able to tell our own personal narratives in such a way that they illustrate a bigger story — it gives concrete examples that people can really grasp and learn from.

TS: I appreciate hearing this in the context of stages of a movement. Could you say more about that, and more about your assessment of what stage we’re in now?

CH: Sure. Going back to this point of how the table was set for the stage we’re in now, I think our network of leaders on the ground has been what has gotten us here. I’m talking about the coming together of the Poverty Initiative and Kairos network, with the network that Reverend Barber and Repairers of the Breach and Moral Mondays have built in the South.

The conditions post-2008 matched with a consciousness that had been developed over the years, and that’s what helped to plant seeds for a campaign of national scope that we have now with the Poor People’s Campaign.

The Poor People’s Campaign’s 40 Days of Action in 2018 was one set of tactics. And of course, the Campaign itself is just one piece of a larger puzzle. It’s one among many organizational vehicles we need. This overarching strategy comes from a deep history of uniting the poor and dispossessed in whatever organizational form, whatever structures, and whatever tactics we can figure out. We have to be flexible. Reverend Barber will often say that “we have to keep a screw loose.”

What we need are leaders who recognize how to take advantage of the political moment. We’re in a different political moment than we were in 20 years ago. Before 2008, you couldn’t even say the word “capitalism.” Today, there is a pandemic laying bare the ways the system discards the poor and lets us die, even while calling us essential. There’s a lot to do, to continue with the strategy and tactics we’ve used, for leadership development and making the struggle our school. Being able to apply our theory in a context of really building a network and building unity among poor and dispossessed people is critical.

TS: You came back to this central strategic question of uniting the poor and dispossessed. There’s often sort of a pregnant pause there, because the question then becomes, “For what? To do what?” That’s maybe where we get to the question of the political independence of the class.

CH: Here is where we often return to Dr. King, when he says, “Power for poor people will really mean having the ability, the togetherness, the assertiveness, and the aggressiveness to make the power structure of this nation say yes when they may be desirous to say no.”

Another quote comes to mind, too, from Dr. King. He said, “When a people are mired in oppression, they realize deliverance when they have accumulated the power to enforce change. When they have amassed such strength, the writing of a program becomes almost an administrative detail.”

At this stage, we’re not there yet. We are able to push for certain concessions, but we’re not going to win everything. But what we are able to do is show that we are building power and shifting the narrative.

How do we get to the point where we’ve built the unity that is needed, so that as Willie Baptist says, “we’re not setting the table so someone else can eat?” How do we get to the point where we set the table and can invite others in, and be the ones setting the agenda?

In terms of building political independence, right now we’re caught in a political structure that plays us off of each other and continues to let those in power maintain their power. That can look daunting. But if we look at history, we can also see that it is in times like these that there are major splits in political parties, and there can be room for the establishment of new political formations. That doesn’t happen overnight, but when you have moments where conditions are right, alongside enough amassed unity, there opens a possibility to develop an alternative to what exists right now.

We have to be ready to take advantage of these moments when they come, because we are organizing to win. You asked why we are working to build the unity of the poor and dispossessed, for what? — Because we have to! Our lives depend on it! Building the political independence of the poor is not about building our own alternative system for our own isolated community. It is about ending the system that is killing our people day in and day out. We must become the new and unsettling force, because when we lift from the bottom, everybody rises.

Charon Hribar, PhD, is the director of cultural strategies at the Kairos Center for Religions, Rights, and Social Justice and the co-director of cultural arts for the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival. Over the past sixteen years, Hribar has been dedicated to the work of political education, leadership development, and integrating the use of arts and culture for movement building with community and religious leaders across the country. Charon is also a leader with the NYS Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival, the University of the Poor, and the Popular Education Project, as well as a trainer with the Veterans Organizing Institute.