by Kevin Kang

Introduction

In University of the Poor spaces, we often speak of the political strategy of “uniting the poor and dispossessed as a social force to win over the middle strata to the program of the poor as opposed to a program of the rich.” This political strategy is not a formulation our network has derived out of thin air, but from study of successful revolutionary processes in human history in which masses of people took control of political power to reorganize society and economy to the needs of the many. These experiences inform us that if we are to win, we must find a path to power that wins over a section of the middle to our cause.

The question of “the middle” is not just a question we must analyze, but also a question the ruling class is analyzing, which in their view, “suggests that a large and secure middle class is a solid foundation on which to build and sustain an effective, democratic state.” In our terms, a stable middle strata is what stabilizes capitalism, and for the ruling class, an unstable middle spells a recipe for disaster for their rule and the continuing exploitation of society. This article explores and suggests the U.S. middle strata is undergoing polarizations today that undercut this stabilizing effect, and offers insights to how we can win over sections of this strata to the program of the poor over the program of the rich.

So what exactly is the middle strata?

While there is no exact definition or specific formula to identify the middle strata, we can understand the composition and makeup of the middle strata by looking at the economy at large, how things are produced, and its associated occupations.

In the University of the Poor’s Study of the Russian Revolution process, we understand the middle strata at that time were not primarily from the working class, but the peasantry. So at certain moments in history, the middle strata were not necessarily part of the proletariat; that is to say, in a relation of wage-labor. In fact, it is in this context that most revolutionary processes have succeeded.

In the period leading up to the Civil War in the United States, the middle strata consisted of artisans, craftsmen, small shopkeepers, settlers, and yeoman farmers from the Midwest, as well as merchants, who were distinct, but connected to industrial workers and the industrial mode of production. However, this was in a context where industrial capitalism was on the rise, commercial agriculture was becoming a bigger part of food production, and the U.S. was going through a period of western expansion. These examples tell us it is important to understand that the composition and makeup of the middle strata changes as economies and modes of production change.

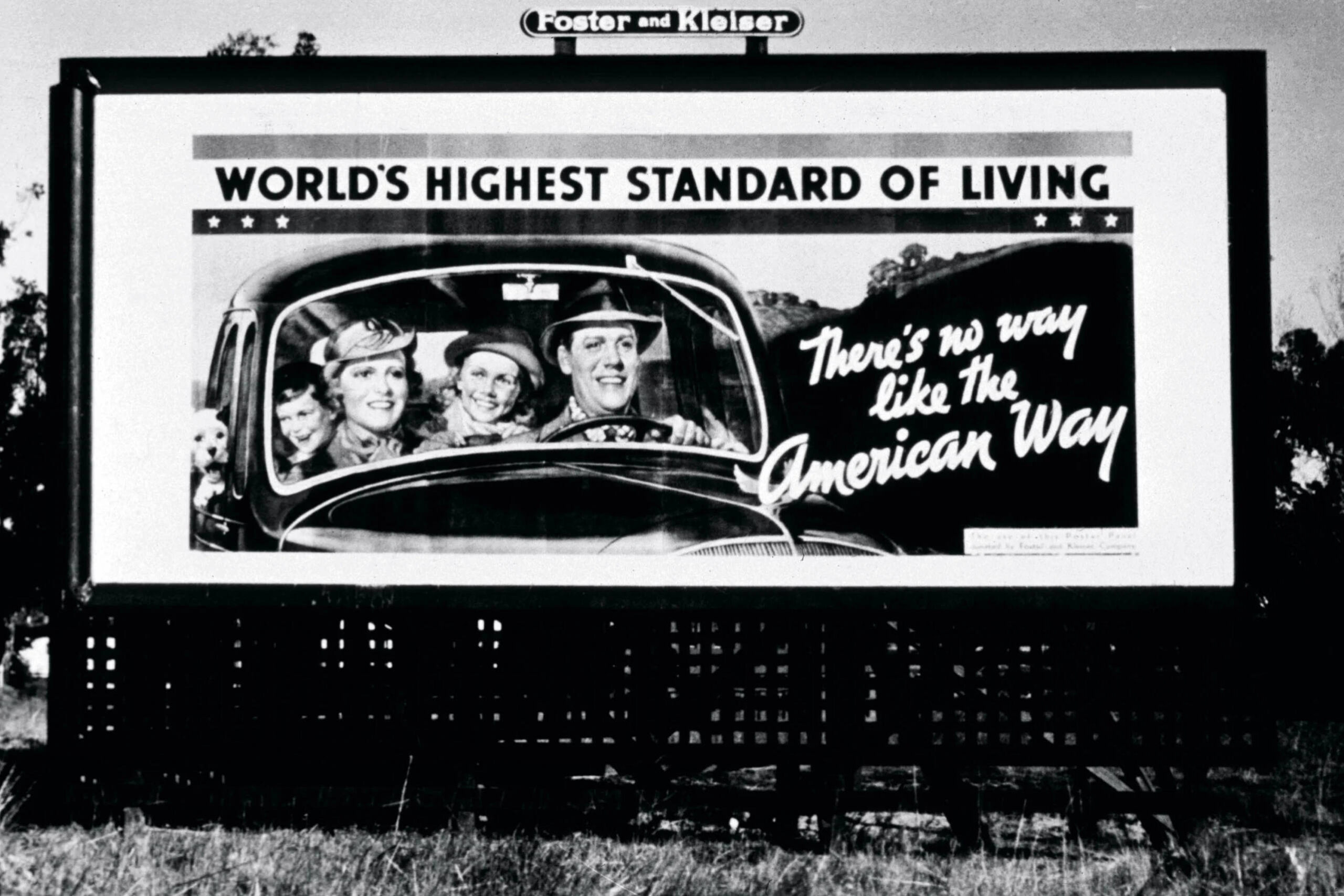

Another important aspect of the middle strata is its vacillation or volatility. Being a part of the middle strata doesn’t firmly place oneself in the ruling class or on the side of the poor and dispossessed. In Germany during the 1930s, an economic crisis and losses from World War I gave the basis for the middle strata to support facism as a solution to their problems. In the 1940s to 1970s, the U.S. middle strata expanded and grew because of a post war economic boom, union-backed wages, expansion of education opportunities, and a growing welfare state. This ultimately created a basis of support for the expansion of capitalism and U.S. engagement in the Cold War with the Soviet Union.

Understanding the U.S. middle strata today

In short, the middle strata today consists largely of wage and salaried workers, predominantly in the service sector. While most economists would describe this grouping as the “middle class,” we choose to use the term “middle strata” because we use more than income to understand how the middle has changed over time, but also the relations to production, or kinds of occupations that one holds. Throughout history, we rarely see a middle strata’s composition change due to drops in income in one recession, but through structural changes that alter how commodities and services are produced. The essence of objective polarization today is caused by changes through technology and automation.

The table below provides a snapshot of some of the most common occupations in each income bracket.

Not included in the chart above are almost 14.6 million people who are self-employed or, in other words, own small businesses. This section would also include freelancers that provide skilled services in IT, marketing, business consulting, and creatives.

The context of occupations in the U.S. middle strata today is placed within changes that have been taking place to the economy since the 1970s with the advent of the technological revolution and globally reorganized production. Jobs that were once prevalent 50-60 years ago, primarily in manufacturing, mining, and agriculture, have declined drastically, largely due to labor-replacing technology. These jobs have to a certain extent been replaced by jobs in the “service economy,” which is a broad category in itself, but include occupations tied to transportation, wholesale and retail trade, services, finance, public service (government), and more. Within the service-producing industry, service industry jobs are found in legal services, hotels, health services, educational services, and social services, among others. Simply put, today’s middle strata compared to previous periods is focused on providing services as opposed to making things.

In addition, union jobs used to be the backbone for middle strata jobs, particularly in manufacturing. The Midwest 50 years ago was full of manufacturing jobs and had the highest concentration of union workers in the U.S. Both the number of manufacturing jobs (as much as 88% of total manufacturing jobs), as well as unionization rates, have gone down significantly. Place this in comparison to some occupations today like education (13.1%) and those related to transportation (16.7%) that still have some of the highest rates of unionization, although as a whole, unionization rates are low. It’s not a coincidence that occupations with the highest unionization rates are also those that have been the most resistant to automation and the technological revolution. But even this is about to change, as the pandemic has accelerated online learning schemes, and automated driving is well within the horizon with increased 5G capacity. It’s worth noting here that as we discuss changes to the composition of the middle strata, many people who are in the ranks of the poor and dispossessed today are coming from dislocations caused by the decrease in manufacturing and union jobs.

What about the middle strata is polarizing?

In the coming years and decades, we are going to witness an increasing polarization and destabilization of the middle strata. This poses as much of a concern to the ruling class as it provides an opportunity for our cause. In fact, the powers that be see a direct correlation between this destabilizing middle with the upsurge of populist movements.

Structurally speaking, the increased digitization and automation of the economy will increasingly polarize and suppress the real wages of the majority of new jobs that will be produced. A study of the effects of computerization show that within the next 10-20 years, about 47% jobs are at “high risk” of being permanently deleted from the economy, particularly those in transportation and logistics occupations, together with the bulk of office and administrative support workers and labour in production occupations. These losses are not just geared towards “routine-based activities,” but are now creeping towards white-collar office jobs in industries such as healthcare and financial services. These processes will continue to be accelerated by advances made in artificial intelligence and deep learning software.

Secondly, the 2007-08 Great Recession is an indicator of the scale and depth of recessions to come, namely in the areas of falling labor participation rates or job recoveries with lower real wages and unequal recoveries. The table below shows how job recovery in 2007-08 took much longer and had greater depth than the three previous recessions. The table below (Figure 2) shows that the bulk of jobs that did come back after the recession came with lower wages.

Part of understanding the “lower wage job recovery” is connected to the previously mentioned structural changes in the economy, “where job opportunities are declining in both “middle-skill,” white collar clerical, administrative, and sales occupations and in middle-skill, blue-collar production, craft, and operative occupations.” Instead, job opportunities have been polarized into “high-skill” jobs in professional, technical, and managerial occupations, and “low-skill” jobs in food service, personal care, and protective service occupations. During recessions, including the most recent pandemic-induced one, capitalist firms use the opportunity of layoffs to reorganize their human resource needs and develop “labor-saving technologies” to maintain output and profit.

As for small businesses, the most recent pandemic-induced recession has had a centralizing effect that shows us what is to come in the future, as over 100,000 went permanently out of business, simply due to the fact that they could not weather the recession like larger businesses and corporations. As the role of technology increases in the operation of businesses, so will start-up and entry-to-market costs, discouraging future small business development.

Along with these developments, the middle strata have increasingly maintained their standard of living by accumulating more debt, with consumer debt recently reaching a new record of $14.3 trillion. Increasing financial insecurity, along with the other factors mentioned above, spell a period of massive dislocation and upheaval in the years ahead.

So what does this all mean for our political strategy of uniting the poor?

Today, the economic polarization of the middle means a great deal of polarization in politics. We can see the most recent political events, from the election of Donald Trump to the rising popularity of Bernie Sanders and “socialist” ideas, as well as the declining trust in U.S. political institutions, largely as a reflection of the condition of the middle strata, as well as a stable capitalism in crisis.

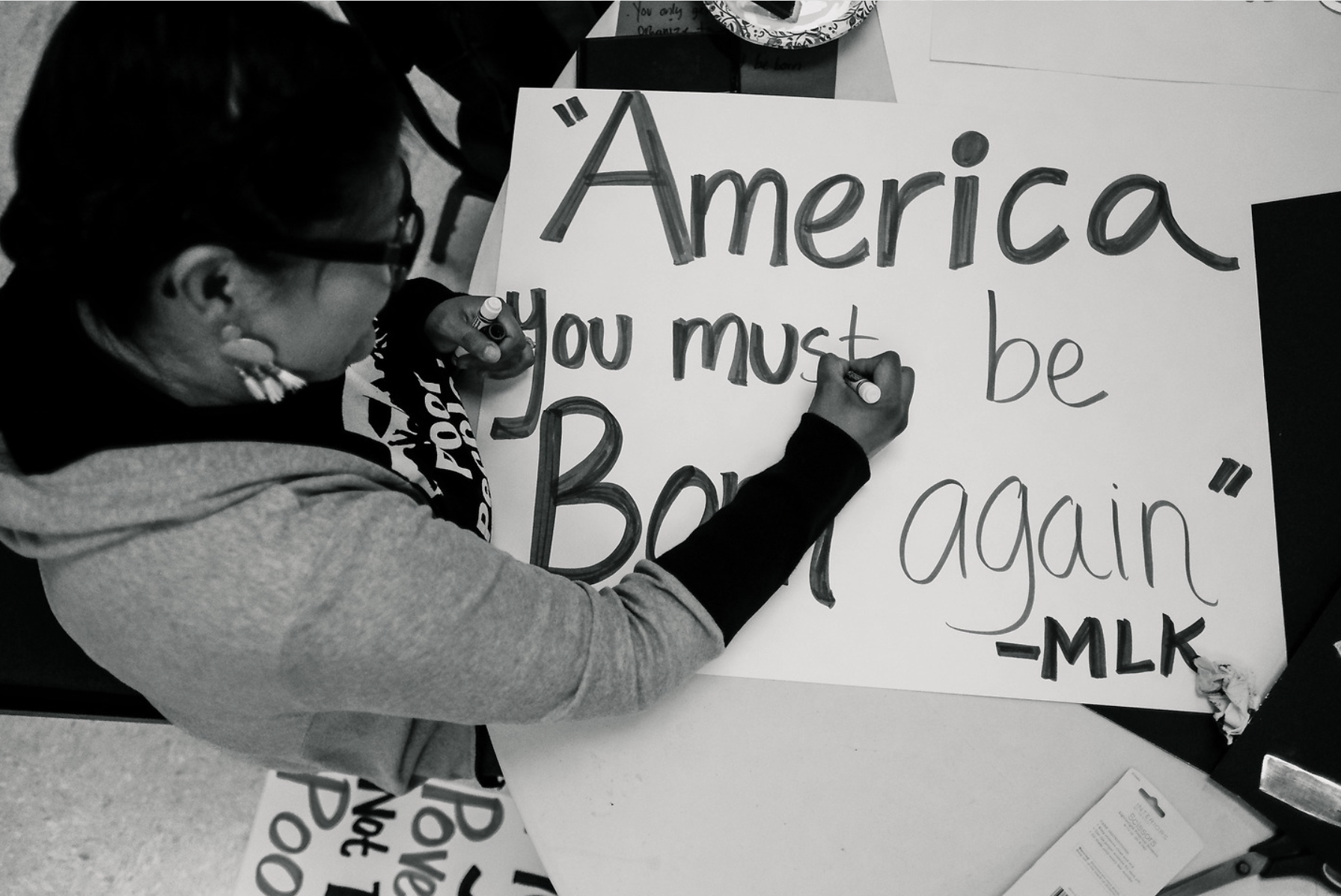

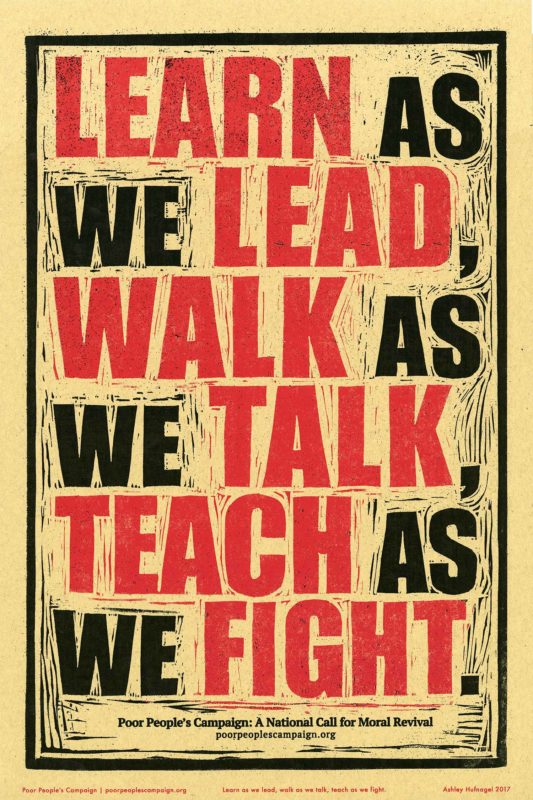

We also need to understand and be aware that large sections of the middle strata are being propelled towards the ranks of the poor and dispossessed. This article attempts to highlight some of the key factors as to why they are being propelled, but more study must be done to get a more accurate assessment of where and who to organize. The Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for a Moral Revival estimates that there are currently 140 million poor and low-income people in the U.S. representing a broad and multi-racial group of people who are facing the brunt of today’s attacks from capitalism, and that is where we must focus in our efforts to identify and develop leaders. But we must couple this with an attention to how we can win over and unite with other sections of society. The falling section of the middle strata today presents a key population that has an objective basis of uniting with the program of the poor.

We must be vigilant in understanding these motions to identify opportunities to identify, unite, and develop leaders coming out of material struggles of the middle in freefall. To be sure, the ruling class is becoming increasingly aware and vigilant in attempting to secure the middle. Discussions around universal basic income and reinvigorated attempts to increase government spending around infrastructure and social programs, and adopting the language of poverty prevention, are a part of their maneuvering.

As history teaches us, organization lags consciousness, and consciousness lags conditions. We can expect sections of the middle at first to disagree or to be actively against our political strategy. But as we continue to develop politically independent organizations of the poor around material struggles, whether around housing, healthcare, or issues surrounding people’s future and livelihoods, they can serve as rallying points for our cause and direction.

Kevin Kang is a member of the University of the Poor and the Popular Education Project, and comes out of experiences in immigrant rights struggles.