By Nelson Peery (A founding and leading member of the Communist Labor Party), written in 1988

Watts was the opening battle of a war that was to rage for three years. It was the greatest civil disturbance since the Civil War. It was not a struggle for civil rights. It was an uprising against a brutal and alien state power. It was to the coming struggle what Lyons of 1836 was to the Paris Commune or what the Commune to the Soviet Revolution. Historically, it was not a “black rebellion.” It was the first uprising of the most exploited and oppressed section of the proletariat.

Twenty-three years is a long time to remember. Twenty-three years hones down and replaces rough and painful memories with softer things. Sometimes when I think of that morning on a black sand beach in the Soloman Islands I remember the crazy love dance performed by two ugly land crabs and I hardly ever think of Joe Henderson who lay beside me in front of those crabs, his guts ripped out by shrapnel – the blood in his throat drowning his scream as he gyrated and writhed and my throat so dry and tongue so swollen with terror that my cry for the medic was hardly as loud as his death rattle. But I remember how the crabs danced on – answering the call of Eden – producing new crabs to guard the black sands of the Solomons.

Twenty-three years have passed since a time known as Watts. And I remember Watts – all of it. I will never forget one image or one political lesson. It is more important that we remember Watts than the Solomons. It is more important because the future was birthed there. Like all futures, Watts – the thunder and lightning of the coming storm – was shot and stomped upon until dying but not dead, it crawled back into the warmth and protection of the earth. There its wounds were bathed by those thought dead at Haymarket and Harper’s Ferry. There Nat Turner, his bones all broken from the slaver’s rack and surrounded by all the thunder and lightning of his time, cradled Watts and said again, “It was not in vain – did they not crucify Jesus?”

Our class enemy has never learned, but when the hanging’s done and the embers at the burning stake are grayed and cold, the conquered bodies of martyrs become the unconquerable ideas. So it is with Watts. Held back by a mountain of bribe money and drugs and the terror of the fascist police, the spirit of Watts remains alive – the uprising that points the way to revolution.

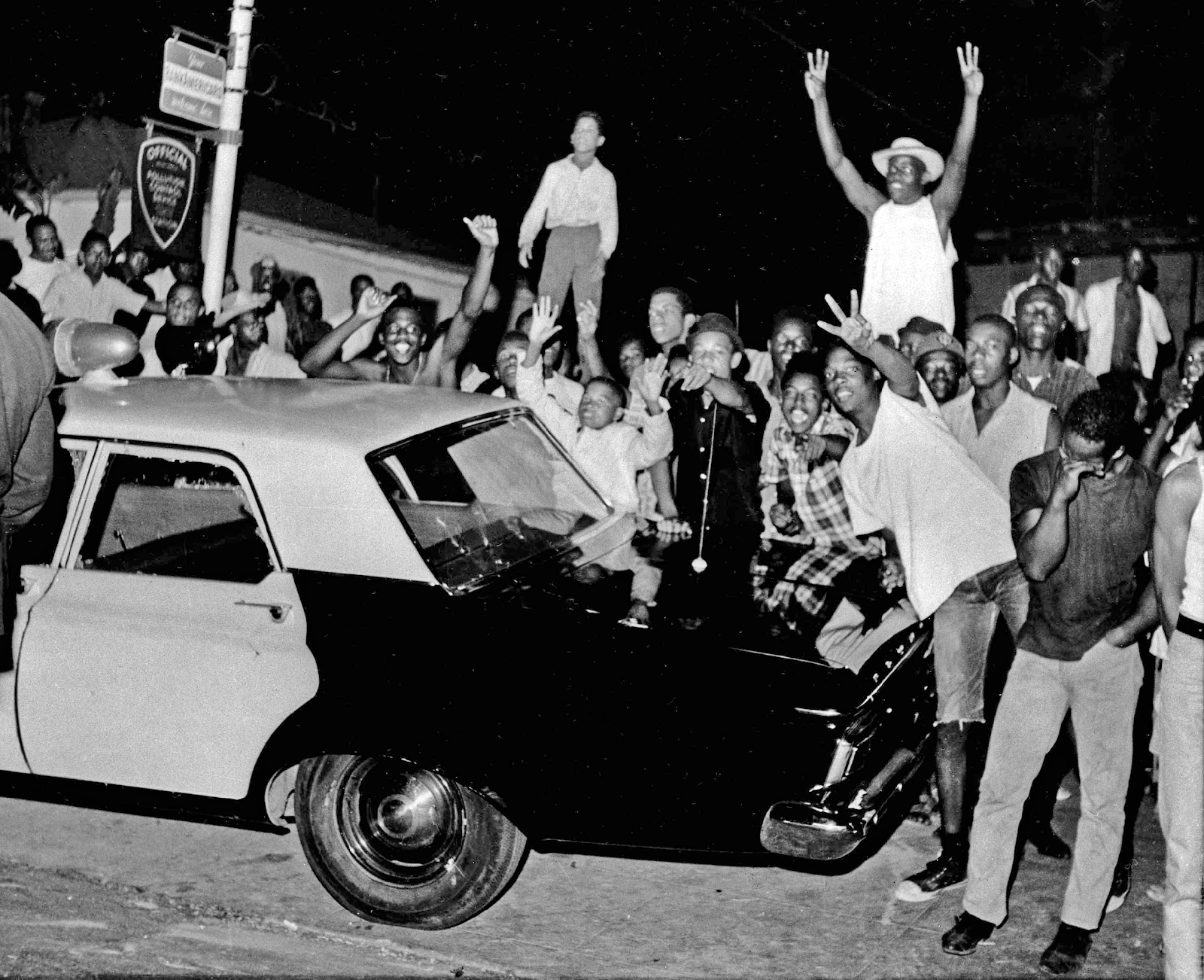

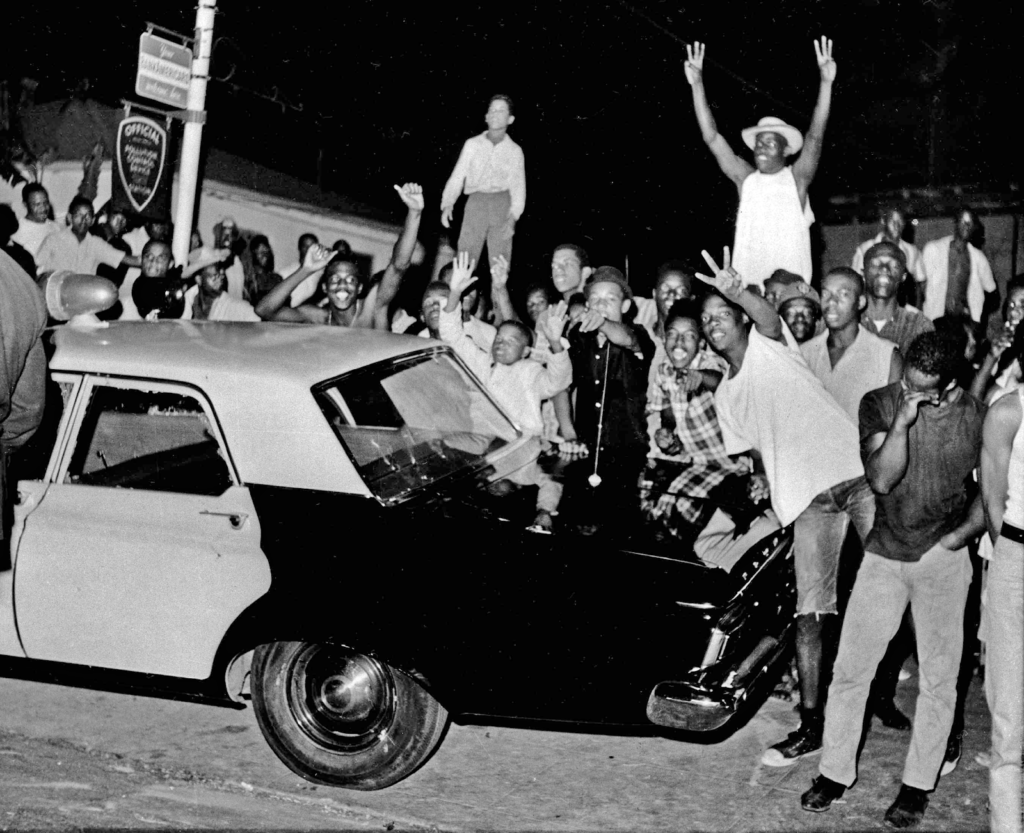

To a communist, uprising is the most beautiful word in the language. More beautiful than revolution. The dumb can speak, the deaf can hear, the uninspired become heroes, the sloth becomes a prophet. Uprising! Off your knees! “Arise ye starvelings from your slumber!” Watts was the supreme uprising. Its great historical significance lies in this: that for the first time the black proletariat independently rose to it feet and glared with hatred and contempt at its leaders, the black bourgeoisie, who now stood on the police side of the barricades, exposed as the coach dogs of the enemy, calling for them to calm down and go home.

And the significance of Watts lay in the unrecorded little and big deeds and incidents that prove that the fighting proletariat of our country is capable of uniting and winning.

The women of “fascist” all white South Gate heard on the radio that the children of Watts were starving. All the stores were burned and the police would not let the people out of the battle zone. The women went door to door and in one day had three truckloads. The noble bricklayer, Cliff, and his band of South Gate Hell Angels helped the women unload the trucks at 97th and Alameda – they were afraid to go any further. As they were leaving one woman scratched a sign “for the children.” And the women of Jordan Downs lined up, quietly divided the food, and took it to their little ones in bullet-ridden project.

By the afternoon of the second day the LAPD and the Highway Patrol had been driven for Watts. Pax Romano had never known such tranquility. Black men and women greeted one another with the Victorian politeness they had learned at the firesides in the South. Not one home had been damaged. Lum, the Chinese merchant on Mona [Street] who overcharged on everything. But always gave credit and hardly ever got paid by the ADC mothers at the end of the month, stood smiling beside his crude sign that proclaimed, “Me Colored Too.”

But the ruling class didn’t want peace and tranquility. They wanted law and order. They called for the Marines. By late morning of the third day the Marines were moving in and the park on 103rd and Central was their staging area. They came in a huge convoy – these freshly scrubbed white and Mexican youth from the training grounds of the El Toro Marine base. As the first truck of Marines unloaded one said to another, “I heard there’s a communist revolution going on here.” The other said, “Those people ain’t communists – they’re poor colored people. I live right over there in South Gate – and I ain’t gonna fight them.” The Sergeant overheard them and went to talk to the Captain. The Captain talked to the Colonel. There was confusion and milling around for several hours and by nightfall the Marines got into trucks and went back to El Toro.

Then they called in the National Guard. The convoy of soldiers regrouped where the freeway passes over Manchester [Blvd]. Two white officers and a black driver got into the front jeep. The officers glanced at one another, and thus assured, looked contemptuously at the blacks standing on the corners of Manchester and Broadway. The driver unconsciously moved as far away from the officers as possible and gave a broken toothed “hey, black brother” grin to the sullen glares of the people. The convoy got under way.

A few blocks south, a 17 year old Wattsonian – his face immobile as bronze – crawled along the bushes to the stairs of the new pedestrian overpass. Halfway up, he pulled a single shot .22 rifle from his pants.

The convoy passed Main Street and then Central. The white officers began to breathe easier and the black driver began to watch the road more than the alleyways and rooftops. It sounded like a ladyfinger firecracker. They could not have heard the “crack” as the firing pin hit the shell. But they knew they were under fire when the .22 long shattered the windshield – and lodged in the cushion of the rear seat not two inches form the second officer. The Watts warrior sent the second shot through the window of the first truck. A frontal assault by the entire Eighth Siberian Army could not have caused greater confusion. Guardsmen jumped from the trucks – some looking for something to shoot at – others seeking protection behind and beneath the trucks. The young defender of Watts crawled down the steps and through the vacant lot to the alley. When he emerged at Juniper he was walking stiff legged with the aid of a walking stick. The LAPD passed him – shotguns at the ready. He never looked up – leaning on his walking stick, dragging and swinging his game leg, he limped to the safety of Jordan Downs.

By the evening the Guard began to occupy the area, setting up a machine gun nest on the corner of Juniper and 97th where they could fire into the Projects. One young white solder said to another, “I hope I don’t have to kill anybody.” The black Sergeant standing behind him unbuckled the holster of his .45 and said, “You’d damned well better not – my parents live over there.”

Mrs. Kinsdale had no such defenders. The 54-year-old grandmother was driving home from work. She didn’t know about the curfew, nor did she hear the shout to halt. The Guard opened up on her with a water cooled machine gun – cutting the door of her car off the hinges so that the top part of her body fell into the street while her car carried the lower part into a flaming crash on Alameda [Street]. Her neighbors, hearing the shots and the crash gathered in horror around the half of her body that lay in the street. Her Minister turned away sobbing “God damn them to hell.” His hands over his face to hide his tears, he staggered toward 103rd where the soot grimed fighters darted between the burning buildings, answering the murderous shots of the police with gasoline bombs and rocks.

They were becoming more conscious of the historic meaning of their struggle. They were seeking an identity and different groupings were now uniformed with “do rags” and red armbands. The uprising began to take on new meaning.

The Guard added the murder of a 14-year-old pregnant woman to its list and a new wave of hatred was added to the revulsion. Chief Parker and Mayor Yorty conferred with the Governor – the Guard will have to go, they are only making things worse. And the Guard wanted out before the black Guardsmen rebelled and joined the uprising.

By the morning of the fourth day of fighting, a group of leaders began to emerge. They were not organized in any real sense of the word, but their ideas were accepted by an even more disorganized people. It was clear to all that the Molotov cocktail and the stone were no match for the M-15s and automatic shotguns that were being used by a police force that was nothing less than a reincarnation of Hitler’s Storm Troopers. If the resistance was to continue, the people had to get guns. The Klan and Nazis had already raided the armories (no one seemed to be concerned with them) and all armories were under military guard. The only source of weapons was the fortress-like White Front department store. The windowless concrete bastion had only two openings – huge steel electronically controlled front and back doors. It was surrounded by police and its 4,000 rifles and half million rounds of ammunition were considered safe. The people were warned of the danger and asked to come down. 10,000 showed up. At a signal they pretended to push toward the police in the front. The police rushed the crowd swinging their clubs. The police in the rear left their posts running to the front to give assistance. Men hidden in the back used ladders to reach the roof. A hole was chopped. An electrician dropped through and opened the gates. The men, eager for battle with their new .30-.30s, poured out of the huge front gate. The police, caught between the crowd and the armed men, fled. The guns were passed out. Now it would really be war.

The 14th Armored Division was at sea, on its way to Vietnam. It received new orders from the Pentagon – Invade Watts! With tanks and helicopters and murderous brutality it did in two days what the police, the highway patrol, and National Guard could not accomplish. But they were tied up for a total of two weeks. The National Liberation Front of Vietnam sent thanks to the people of Watts.

Horatio in his epic battle at the bridge was never so alone as was the proletariat of Watts. The Communist Party (USA) confined its protest to the overcrowding of the jails. The newly formed American Workers Communist Party [POC] branded the struggle a “riot” and ordered its cadre to stand clear. The left intelligentsia deplored the violence and missed the historic moment when they could and should have written and sang and shouted a clarion call that would mobilize the world to defend those blacksmiths of history who were casting their dies in the battle that raged on 103rd.

The uprisings that were to follow in Chicago and Detroit and Cleveland and across the country confirmed the historical significance of Watts. Violence inevitably erupts as the proletariat gains it independence. The proletariat demands reform, but there are no reforms. The demands of the class are met with violence. The proletariat fights back. The tactic of the enemy is to crush the fighting spirit and then bribe. But bribery is not reform. We must have reform. Deep in the heart of our consciousness we know that unless there are reforms that guarantee food, housing and clothing the day is not to far distant when a morning sun will call us out to battle once again. Watts proved that the proletariat can gain social hegemony. Watts proved that there will be a proletarian revolution.