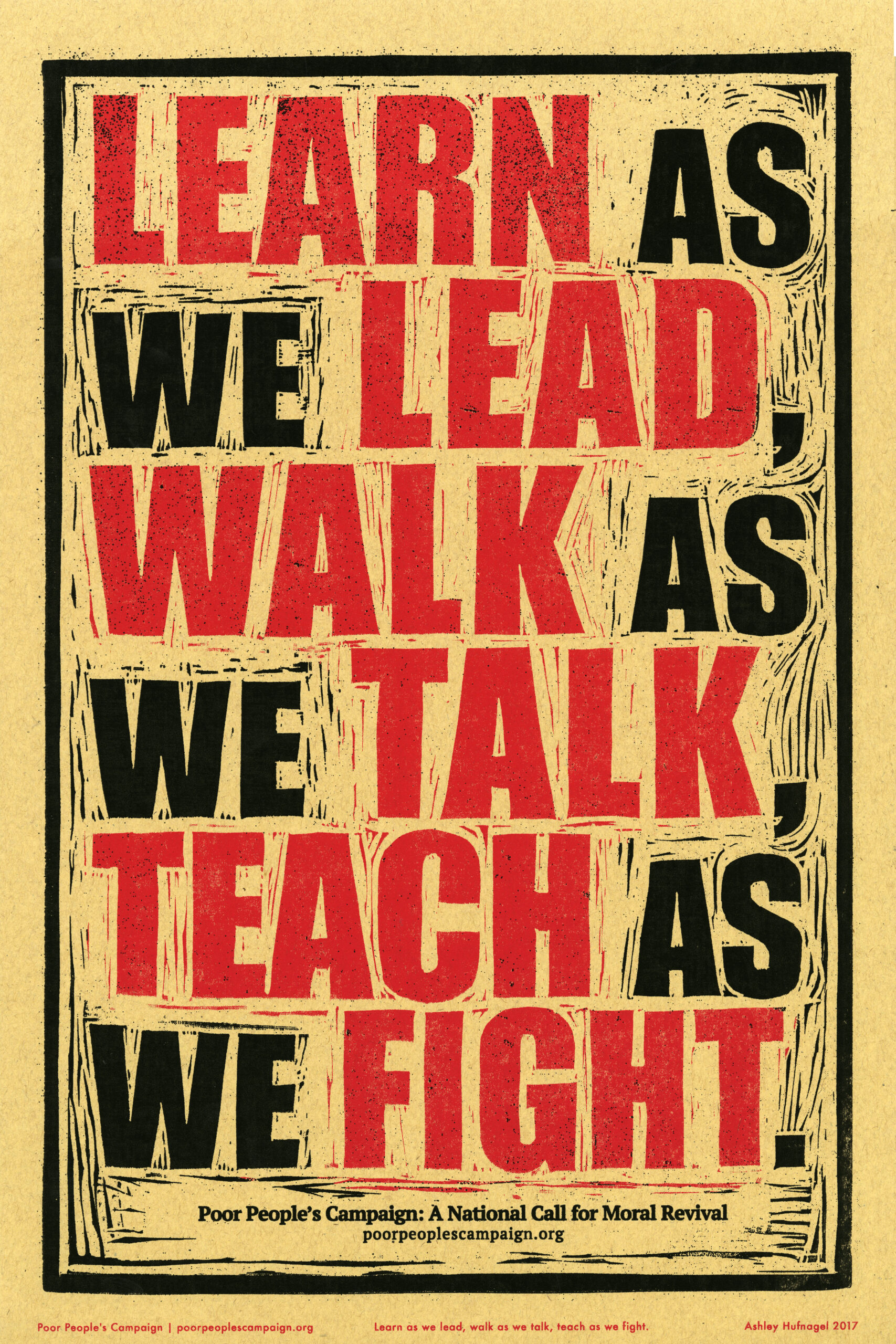

The Fall 2021 issue of the University of the Poor Journal is about “making the struggle a school.”

In the most basic sense, this means learning from the successes and failures of our organizing work so that we can be more effective. We must make honest assessments about what we’ve won and why we’ve lost, as Sarah Weintraub has done. We can’t be satisfied with the style of self-aggrandizement or self-justification required of the nonprofit sector by foundation funders. We need a working-class intellectualism that demands that our questions be heard and proposes sound solutions, as Karim Sariahmed and Ellen Schwartz argue.

In addition, making the struggle a school means reflecting on our own history, as Leonardo Vilchis, Kenia Alcocer and Elizabeth Blaney have done in their piece on the 25 years of Union de Vecinos in Los Angeles. It means studying the victories and defeats of the poor and dispossessed in history, studying their opponents and learning the theory derived from those experiences of struggle.

This is not automatic. Making the struggle a school must be a conscious, active practice, because the kind of reflection and study required of revolutionaries runs contrary to the way we’ve been conditioned. Many times when facing injustice, our reaction is to “Just do something!” John Candy’s character represents this tendency well in the 1995 film Canadian Bacon: “There’s a time to think, and a time to act. And this, gentlemen, is no time to think.”

The philosophy of pragmatism has been so ingrained in our culture, even in the way we think about work for social change, that it has left us with the feeling that there’s no time to think. Pragmatism was a particular ideological intervention of the ruling class of the late 1800s in the United States, which asserted that “to be is to be useful,” and “the ends justify the means.” The express goal of this philosophy was to create a philosophical framework in which capitalist exploitation was justified. Undermining the principles of scientific inquiry, truth seeking and ethics, proponents of pragmatism instead promote efficiency and usefulness. Ultimately, pragmatism means efficiency for the benefit of capital and usefulness to the capitalist class.

In his 1954 book, Pragmatism: Philosophy of Imperialism, Harry K. Wells notes that the amoral opportunism of the pragmatic approach serves to justify the violence of the owners of capital:

“Such a method is eminently suited to the ideological requirements of a class which in fact employs any and all means which appear to be successful in maintaining and extending exploitation and oppression: strike-breaking, union-busting, red-baiting, violence, frame-ups, spies, goons and stoolpigeons planted in the labor movement; doctrines of racial superiority, social and national discrimination, brutality, all-white juries, ‘legal’ and ‘illegal’ lynching; aggression, atomic bombs, germ warfare, mass murder, genocide. The pragmatic method is perfectly adapted to apologize for, and advocate, ideological lies and murderous force. Expedient opportunism accurately reflects the character of the dying, desperate capitalist class. Knowledge, science, principles of true and false, right and wrong can no longer serve this class.”

Because of our culture of pragmatism, we are made to think of the “struggle” and the “school” separately. We’ll often spend very little if any resources in our organizations and struggles on political education. If we do, we’ll find that political education is reduced to agitational and definitional education, deeming theory as inaccessible, unnecessary, or relegated to the “experts.” Non-profits will subscribe to toolkits and organizing manuals that emphasize a skills-oriented education, but not a thinking-oriented education. We’re not encouraged to prioritize self-study or collective study beyond the “workshops” that are planned. When reflections of the struggle do take place, it can tend to be reduced to the exchanges of personal experiences of the participants without a connection to history or a study of the conditions that surround our organizing work. In this culture, building a movement of the united poor and dispossessed is viewed more as a lofty ideal as opposed to a goal that we can actively plan and work towards.

Making the struggle a school, in its broadest dimensions, then, is a direct attack on the culture of pragmatism, an enduring pillar of ruling-class ideology. Nijmie Zakkiyyah Dzurinko, Phil Wider & Jae Hubay make this clear in their reflections on the interrelated cornerstones of their organizing in Put People First! Pennsylvania: the class struggle, the classroom and the class organization. Indeed, for their own purposes, the ruling class itself does study, discuss, assess and plan, as we see in Bruce E. Parry’s article on the Council on Foreign Relations. Yet for the rest of us, they encourage individualism and spontaneity, tell us to be satisfied with symbolic victories and insist that what’s best for them will eventually “trickle down” and be good for us, too.

We need to respond with sophistication, rigor, and creativity to expose the bankrupt narratives of the ruling class. Two recent publications that stand to make significant contributions to our collective understanding are We Cry Justice: Reading the Bible with the Poor People’s Campaign, edited by Rev. Dr. Liz Theoharis, and Freedom Church of the Poor: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Poor People’s Campaign by Dr. Colleen Wessel-McCoy. They are reviewed here by Adam Barnes and Savina Martin.

We launch this issue of the University of the Poor Journal during an extended period of upheaval and reorganization of the global economy and the international balance of power. The coming period is shaping up to bring even more cataclysmic shifts. This moment also finds us doing self-reflection on our activities in the University of the Poor, an emerging organization of revolutionaries with an inseparable connection to the mass organizations of the poor and dispossessed. We’re proposing that as the contradictions of capitalism continue to deepen, the University of the Poor Journal can become more and more of a space to spark collective dialogue, assessment and sharing of the lessons of our current struggles and of history. We need the science of navigation to help us sail the stormy and rising seas ahead.

– Tim W. Shenk and Kevin Kang, on behalf of The University of the Poor Journal Editorial Committee