The three co-directors of Union de Vecinos present an overview of some of the struggles and lessons learned from the organization’s 25 years of work in the Boyle Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles, California. Conditions marked the terrain of struggle for public housing residents and neighborhood mothers: they learned from a devastating demolition of their homes that they needed an organization led by the people most affected by the conditions in their communities. As Union de Vecinos continues to grow and build power, they offer these stories as a school for organizers.

by Kenia Alcocer, Elizabeth Blaney, and Leonardo Vilchis

Union de Vecinos is the East Side Local of the Los Angeles Tenants Union (LATU). Our work predates LATU and was founded in 1996 by public housing residents to fight against the proposed demolition of their homes by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). At that time, federal, state, and city governments were working together for a plan to destroy 100,000 units of public housing across the country with the false promise of redevelopment. They were not about improving housing for the poor. They planned to reduce public housing and open the doors for private developers and corporations to benefit from the transfer of public resources into the private sector. In Los Angeles, the Housing Authority told the residents of Pico Aliso that they were coming to improve and modernize their housing. What they didn’t tell them was that two- thirds of the community was going to be displaced.

The proposed demolition impacted 1,285 families in the largest public housing development west of the Mississippi. Located one-half mile east of downtown Los Angeles in the neighborhood of Boyle Heights, the residents of Pico Aliso and Aliso Village had a long history of organizing. Before forming Union de Vecinos, the residents of Pico Aliso were organized in Comunidades Eclesiales de Base (CEBs) or Church Base Communities. Every week, the members of the CEBs met to read the Bible and discuss the issues affecting their community. They asked themselves, “How does what we are reading in the Bible apply to the issues that we confront today?” and “What are we called to do to respond to these issues?”. They reflected on the signs of the times and responded to these signs as they were relevant to them here and now, an immigrant community living in the Pico Aliso Housing Projects. After their reflections, they took action and responded to common issues. The CEBs organized against discrimination, police abuse, the criminalization of their youth, and gang violence in their neighborhood.

In January of 1996, thirty-six families received a flyer posted on their door that they would need to leave their homes in thirty days. They knocked on doors, organized block meetings, refused to sign documents agreeing to their removal and formed Union de Vecinos. We were not able to stop the demolition in Pico Aliso, but we did keep three hundred families in their homes during and after the reconstruction. Nine hundred and sixty-six families were displaced as a consequence of a false promise of development. We learned from this struggle, became strong, and decided to fight an organized battle against displacement and to rebuild our neighborhoods on our own terms.

One of the founding principles of Union de Vecinos is that the work is always determined by our neighborhood committees. We focus on the people most affected by political, economic, and socially oppressive conditions and take their lead. When the proposal to demolish Pico Aliso came to the community, residents were on the board of a non-profit. At the time, the board of directors was made up of 34% community residents and 66% professionals. Despite the fact that the community would lose their homes and be relocated, the professionals voted against the community board members and in favor of the demolition. We would never be in that position again. We created a structure in Union de Vecinos in which the most poor and the most in need in the community are the ones who direct and decide the work in which we engage. In 2000, we won the best practices award from the United Nation Huairou Commision for our organizing model.

Union de Vecinos point of departure is the experience of our community members. We believe that the problems of poverty can only be solved by giving power to the most affected. They are the ones best suited to coming up with the best solution. To get there we need to go through a long process that goes beyond just a single campaign. It is a process of transformation. We transform our reality and, as we transform that reality, we transform ourselves. We define the terms of that transformation and we take the initiative ourselves as we negotiate and push back against those who try to impose their own self-serving solutions. But we can only achieve that transformation if we are organized in our blocks, in our neighborhoods, and in our city.

To highlight an example, in 2004 we expanded from public housing into other neighborhoods and formed neighborhood committees. Several of our neighborhood committees identified safety in their neighborhoods as a primary concern. Safety was defined in terms of safety for pedestrians as we move through the community. This includes safety from cars and safety from other forms of violence on the streets. In our Folsom Neighborhood Committee, the mothers were afraid to let their children play outside after school. At the beginning, they wanted more police patrol cars to keep them safe. This is the starting point for where the mothers were at. We started from that place and discussed what the role of the police was in the neighborhood. What did they do? Did they help or bring more harm? We began to talk about fears and the conditions that create violence. They realized that the police were not the answer.

Through these conversations, the mothers learned that they needed to challenge some of their fears and to reclaim spaces in the neighborhood. They started with the alleys which are an extension of their backyards. They closed off the alleys and organized activities every Friday night in the summer. This led to conversations about how the city of LA failed to provide adequate lighting and street repairs and how the city failed their neighborhood overall in providing basic resources. The mothers decided that they would install lighting, fill potholes, organize cleanups and plan regular activities in the alleys. They became owners of that space.

In this process, they had to address the issue of others who were using the space for different types of activities. The first day they closed the alley, several of the gang members didn’t like being kicked out of the space. The mothers explained to them what they were trying to do. The next week, those same gang members joined the mothers in organizing the activities. They built relationships and learned not to be afraid of each other. They had a common goal to make the neighborhood better for everybody.

Eventually, one committee expanded to 5 neighborhood committees in a 1 ½ square mile radius. They worked together to close off streets for swap meets, creative play, and building physical improvement projects. When they decided to organize a major celebration and inauguration of several of their projects, the city said they had to pay LAPD $2,500 to provide protection for the event. The mothers refused because that would imply that their event was unsafe and community members would not come. The committees worked their way up the chain of command, postponing their own celebration. They met with police chiefs and explained how they themselves had changed the neighborhood over the last 8 years into a neighborhood that was safe to walk, where community members knew each other and built networks of support. After two months of pushback, the mothers held their celebratory event without any police presence.

This was a transformative process that took eight years. Community members changed their material conditions through action, reflection, evaluation, more action, bringing in their own knowledge and experience, and challenging and growing from basic assumptions. It was a process of constant movement, growth, and community building. It’s not something that you can learn in the classroom. They learned it through engaging in the struggle.

In 2004, we also started participating in Get Out the Vote campaigns with the United Farm Workers. These efforts provided us with the opportunity to train our community on how to knock on doors and how to deliver an effective rap to ensure community participation in the electoral process. We organized by precincts, building voter power. It was a foundation for our further expansion into the neighboring City of Maywood.

The City of Maywood is a small city, 1.18 square miles and with a population of 40,000. It is a small community that has a tremendous impact in the everyday lives of everybody that passes through its streets. Maywood and Boyle Heights are neighbors that are separated by another small city called Vernon. Vernon is an industrial city with only 100 inhabitants. Thousands of workers need to pass through Maywood to get to Vernon. Maywood’s City Council at the time took advantage of this fact and decided to have checkpoints every Friday from 3pm to 12pm. This way they were able to take cars from undocumented drivers who didn’t have drivers licences. The towing company was making 4.5 million dollars a year and these seizures were also the main financing for the City Council members as well as the police department. Padres Unidos de Maywood was organizing in Maywood, heard about our work and invited us to work with them. We started organizing, but the checkpoints were only the tip of the iceberg.

As we knocked on doors and started forming neighborhood committees in Maywood we learned about other issues: a corrupt City Council, a corrupt Police Department, a corrupt election process, 3 superfund sites, contamination from the neighboring city of Vernon, 3 water companies that served contaminated water to the community, children with high levels of lead poisoning, and lack of services and parks in the neighborhood. The community believed the only way to change these conditions was through taking over the City Council. The first election was not easy. The City Clerk who counted the votes was in the pockets of the towing company and the City Council at the time. There was no doubt that fraud had been committed, so we demanded that Los Angeles County take over the voting process. The second time around the community was able to elect their first 3 candidates.

The first thing they did when in power was to declare Maywood a sanctuary city for immigrants and ban checkpoints in the city. But individual political interests started getting in the way and we ended up with only one committed council member. So the community decided to elect 2 women for the other two seats that were up, one who had community ties and was a labor organizer and the other who had strong connections to the church. The opposition decided to recall them, but the community was determined to win and they did. In the past, you could win a City Council seat with 300 votes. Now you need a minimum of 3,000 votes. Our community organizing with increased civic participation 10 times. With this type of community power and leadership, we changed a lot of things in the city from 2006 to 2014.

From our work in Boyle Heights and Maywood, we continued to expand our struggle for the poor. In 2015, we co-founded and joined a process of organizing and community reflection across the city of Los Angeles around the issues of gentrification, community displacement, and democracy in the city. These efforts led to the founding of the Los Angeles Tenants Union. The tenants union establishes local neighborhood chapters across the city. Locals organize around neighborhood issues and help link neighborhood struggles to the larger movement for housing justice. This struggle required that we grow beyond our neighborhood block into the city to build a people’s democracy in a people’s revolutionary process. It is within the struggle that we see transformation in the material conditions and within our members themselves. But the struggle never ends. We need to grow in our fight, block by block, city by city, until we have justice for all

Elizabeth Blaney is a former CPA turned community organizer and popular educator who has dedicated her life to building an organized base of community members fighting to change the political, social, and economic conditions that create oppression. In 1996, she co-founded Union de Vecinos, a grassroots community based organization that formed the first tenant union in East Los Angeles and co-founded the citywide Los Angeles Tenants Union. Twenty-three years later, she continues to work at Union de Vecinos, Eastside Local of the LA Tenants Union, organizing neighborhood committees and tenant associations to create community based solutions to dismantle systemic conditions of exploitation and racism.

Elizabeth has served on the boards of various non-profits, the Boyle Heights Neighborhood Council and various Advisory Boards for the MTA. She is currently part of the International Peoples Assembly, that is a global process connecting movements worldwide to fight imperialism. In 2019, she was part of the US delegation to Venezuela, who along with delegations from 90 other countries, met to discuss a platform for united actions supporting the struggles of the poor . She currently is working in partnership with others to develop political education schools in various neighborhoods in Los Angeles.

Elizabeth is also a member of the international artist collective, Ultrared, that works with activists and organizers in London, Berlin, New York, and Los Angeles on a range of social justice issues.

Leonardo Vilchis is a co-founder of the Union de Vecinos and Los Angeles Tenant’s Union, a resident of Boyle Heights and has worked in the community since 1987. He has over 33 years of experience as a community organizer. He worked at the UFW as a Political Organizing Coordinator and at ACORN as Political Organizer. In the early nineties he worked at Dolores Mission with Christian Base Communities and was their lead organizer. He was trained in liberation theology in Costa Rica, is a popular educator, and conducted nonviolence trainings with Pace e Bene in Colombia and in various cities within the United States. He served as a Planning Commissioner for the City of Maywood and on various other boards. He is a member of the international artist collective Ultrared. He gives various lectures and panel discussion on community organizing, popular education methodology and various other topics

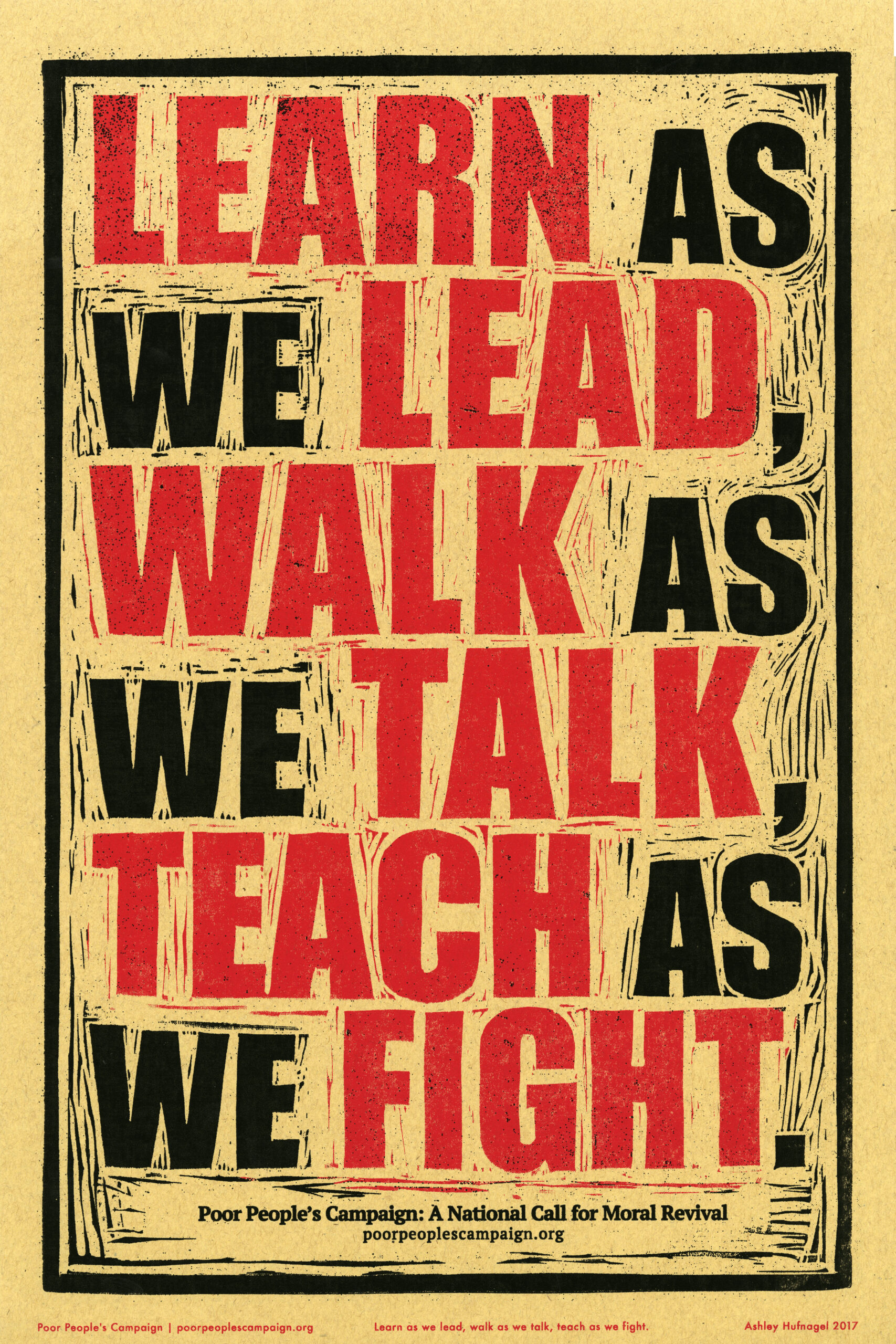

Kenia Alcocer is a housing rights organizer with Union de Vecinos/ Los Angeles Tenant’s Union and Co-Chair of the National Steering Committee of the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival. She immigrated to Los Angeles as a small child, witnessing the ’92 riots after the acquittal of four white police officers in the beating of Rodney King, and later navigating access to higher education as an undocumented person, have been some of the forces that have shaped Kenia Alcocer’s life and work. She is a mother of two and is committed to fight to rid her community and this country of Poverty, Systemic Racism, Ecological Devastation, the War Economy and the Distorted Moral Narrative.