by Nijmie Zakkiyyah Dzurinko

Electoral politics in the contemporary U.S. context are complicated for revolutionaries. As we are all well aware, because of the way our political system is structured, there are very few mechanisms for new/third parties to gain a widespread foothold. We may be heading into a period in which greater political polarization could cause fractures or shifts in one or both of the two major parties. However, the jumping off point of this piece is an examination of electoralism via the Democratic Party, which is currently ascendant among segments of the so-called “left”.

Since people are throwing around a lot of words these days (“comrade”, “revolutionary”, etc.), with very little attention to whether we’re actually talking about the same thing, I want to start by defining my terms and baseline assumptions.

For the sake of this piece, a revolutionary is someone who is working toward a fundamental change in the economic structure of our society. In the way I’m defining it, a revolutionary does not believe that we will be able to legislate our way beyond capitalism using the existing two-party system. We cannot use the existing mechanisms of the state, which function at the behest of the ruling class, to overthrow that class.

Additionally, I make a distinction in this piece between “leftists” and “revolutionaries”; leftists being people who see the world through a left/right axis and revolutionaries who primarily see the world as a conflict between two opposing classes — the working class and the ruling class – or a conflict between the majority, who has been forced to the bottom, with the minority on top. Wherever I reference leftists in this piece, it is not synonymous with revolutionaries.

A key question for revolutionaries today is identifying the revolutionary social force, as well as understanding what stage of the revolutionary process we are in and the appropriate tasks for that stage.

This piece defines the revolutionary social force as the grouping(s) of people in society who objectively have the most to gain and the least to lose from a fundamental re-ordering of the economic system and all other systems that arise from, uphold and mutually reinforce capitalism. In the U.S. today, this is the 140 million people who are living at 200% or below the federal poverty line. The 140 million includes both waged, unwaged and excluded workers, incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people, youth, disabled people, and people of all ethnic and racial backgrounds, including 66 million poor white people. My underlying assumption about the current stage of the revolutionary process is that we are in the stage of identifying, developing and uniting leaders of that revolutionary social force.

Another assumption in this exploration, as mentioned before, is that the Democratic party and Republican party are both parties of Wall Street — i.e. the ruling class. While we can certainly debate and/or assert lesser evilism, the jumping off point here is that there is no major political party that actually represents the interests of the working class in this country. This is not a position of nihilism, or an argument for disengaging completely from electoral politics, but it is one that argues vehemently that we must not fall into a false sense of security or lie to our people about the nature of the two party system.

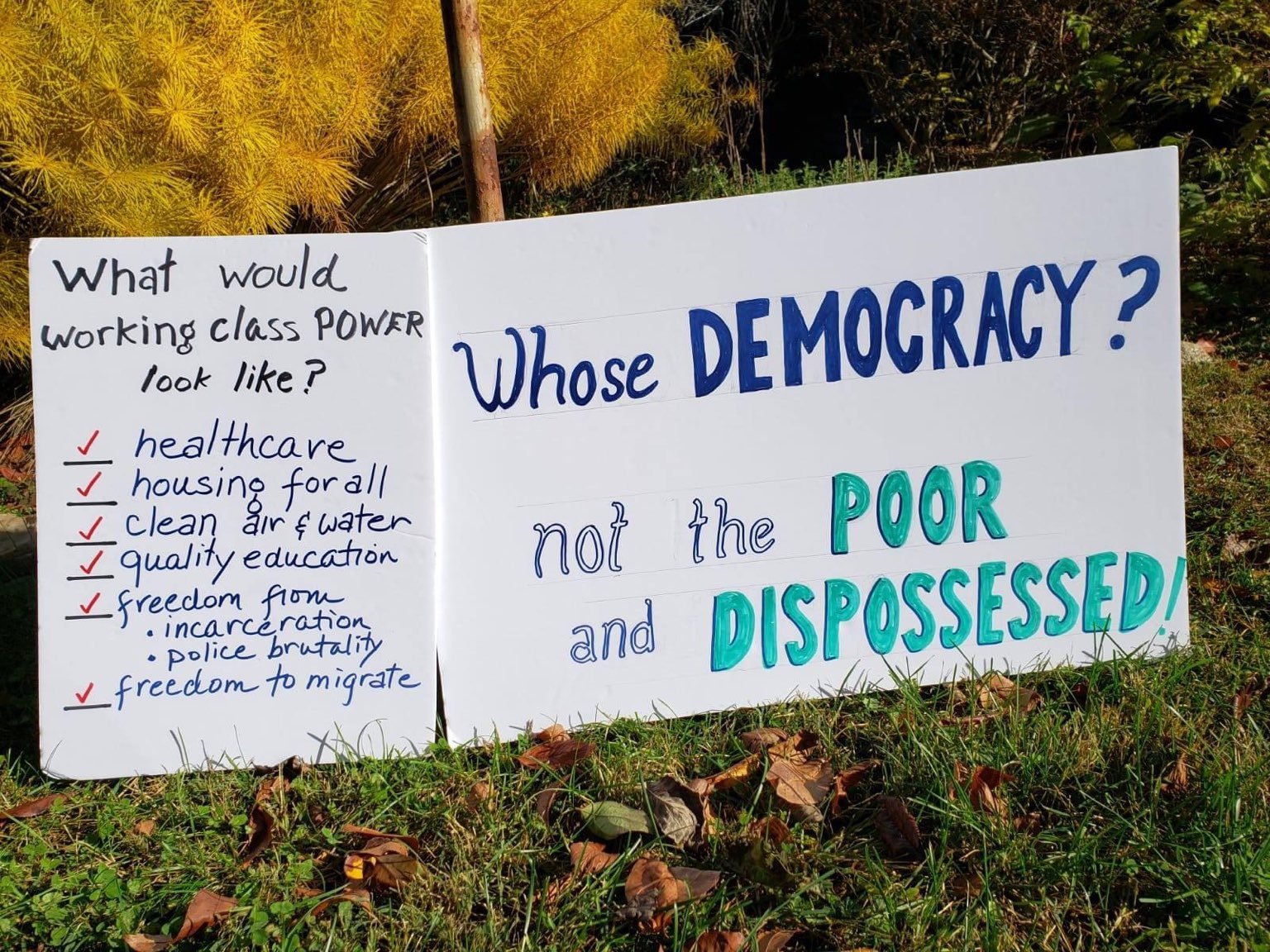

This brings us to the concept of political independence and how the poor and dispossessed builds such independence as a class. Here, I’d like to borrow a definition from the new member handbook of Put People First! PA:

“PPF-PA is independent from both the Democratic and Republican parties. That means that we don’t craft our agenda around the agenda of these parties, but around what people really need. We have a commitment to holding all power-holders accountable. We fundamentally don’t believe that politicians or people in power are going to be able to solve our problems. It is only through a mass movement with a core of clear, competent, committed and connected leaders that changes have happened throughout history. Change comes from below, not from above. We don’t put our faith in the parties, but we are political. However, we will not get drawn into conflict between “republicans vs. democrats” because the primary conflict is not between parties but between our human rights and the power holders standing in the way of achieving them.“

With this understanding of political independence in mind, this piece seeks to explore two fundamental questions. One, if we don’t believe that we will be able to legislate our way to a revolution, and we understand that both the Democratic and Republican parties represent the interests of the ruling class, what is the appropriate tactical use of electoral politics (defined as endorsing and/or running candidates) for revolutionaries? And two, can electoral politics be used to build the revolutionary social force, since this is the primary task of revolutionaries during this period. If so, how?

The contradictions and interpenetration of mental terrain and political independence

To find out whether electoral politics can be used to build the revolutionary social force, we must first consider the mental terrain of this country. For good reason, there is a common sense understanding that when people in the U.S. think of politics, they think of elections. As the ruling class would have it, elections are basically synonymous/interchangeable with “politics”. This is of course very different from what the mass base-building model of the “poor organizing the poor” understands politics to be.

With that being said, there’s no denying that elections are a very important part of our mental terrain. After all, as Marx once put it, “the ideas of the ruling class are the ruling ideas”. Therefore, it’s important for revolutionaries to be engaged in any space that is relevant to the mental terrain of the masses of people. However, it is also true that there are large numbers of people among the 140 million poor and dispossessed who generally do not participate in elections, or participate in them infrequently. So, while there is an overall belief that elections equal politics, and we can certainly find the working class paying attention to and investing themselves in the electoral process, there is also a strong segment of the working class – in particular the most excluded and exploited sections – that doesn’t place its faith in the current political system, is deeply dissatisfied with both parties and votes with their feet (i.e. by not participating).

I would assert that as revolutionaries we do a disservice to the working class to repeat the political science talking point that the reason the agenda of poor and dispossessed people isn’t reflected in national politics is because individual poor and dispossessed people don’t vote. If we understand the state to be an instrument of the class that rules, the more likely formulation is that individual poor and dispossessed people are less likely to vote because we deeply understand that the state as a whole does not function in our interests.

So we need to be aware of both things at once: electoral politics are important on the mental terrain of the working class and the most exploited sections of the working class are not motivated by/tuned into elections. We must hold onto this dynamic even as we understand that the electoral arena can be an important site of building the poor into a “class for itself” – a class that can assert its own political agenda. This point has strong implications for, and calls into serious question, whether and how electoral politics can build the revolutionary social force.

So holding that first contradiction in mind, we come to a second contradiction. Putting aside for a moment the fact that poor and low-income people may not be as present in the electoral arena as the working class as a whole, if the electoral arena is an important site to assert an agenda that can unite and mobilize the poor and dispossessed, it is also essential, as revolutionaries, that we do this in a way that maintains political independence from both of the parties of Wall Street.

Therefore, the method of using elections to build “a class for itself” — without simply delivering voters to the Democratic Party – is of the utmost importance.

What makes electoral politics attractive for “leftists” (not the same as what makes them potentially useful for revolutionaries)

For liberals, progressives and leftists who have been trained in traditional “community organizing” models, who are intentionally trying to be part of a realignment strategy for the Democratic party, or who take their cues from labor unions, there are several things that make electoral politics attractive:

- Elections have a hard goal and a clear cut “win” or “loss” according to numerical metrics. Increasingly, that which is measured can be monetized and the rise of data capital stands to increase the material benefits of working on elections for years to come.

- Elections are time limited – many policy or legislative victories can take years to achieve, while elections run on definitive cycles.

- The bigger the race, the more money at stake, which means widespread exposure in the mass media. Therefore, major elections become an entry point to break through into the attention spans of everyday people and potentially engage a broad audience in one fell swoop.

- It is also very possible, under particular conditions (how much power is vested in their particular office/what they are able to do as an individual/what allies they have etc.), that elected officials, once in place, can lead or collaborate with others on passing policies that benefit the working class. The Philly DA series on PBS is an interesting reference point for this.

In particular, the first two reasons make electoral politics attractive for people who have been trained that the primary thing that motivates people to get involved with and remain committed to organizing are “wins”, without which people lose their motivation to keep going and stay. This formulation is one of the cardinal rules of Alinsky-based organizing.

While revolutionaries certainly believe in rigor, setting milestones, achieving goals and making people’s lives better wherever and whenever possible, our understanding of “winning” is contextualized by the overall understanding that our class is not in power. Our concept of winning and victory is necessarily more expansive, and particularly in this stage of the revolutionary process, focusing on the development of clear, competent, committed and connected leaders is a crucial component of a successful outcome for any initiative or campaign. So I ask again: (how) can revolutionaries use electoralism to organize the unorganized/disorganized, and develop clear, competent, committed and connected leaders?

Over the last few months, I spoke with a number of folks who have worked to get candidates successfully elected, have been elected officials themselves, run their own candidates, and/or engaged in this work as far back as the 70’s through the 80’s and 90’s to today. Below are some key takeaways and lessons that were shared with me on both the limitations and possibilities for revolutionaries engaging in electoral politics.

- Because of the grueling nature of electoral campaigns and the necessary focus on winning, follow-up with voters can fall by the wayside. In order to use elections as mass base-building drives, there needs to be time and attention explicitly focused on follow-up and well-functioning organizational structures to engage people year-round and beyond the election cycle.

- Elections tend to bring out egotism and individualism in candidates, their campaigns and supporters. Additionally, it’s common practice to hype up a candidate beyond what they can actually deliver in order to motivate people to volunteer and vote to get them elected. This results in misleading people about the fundamental reality of our society and how change occurs – a situation compounded by a lack of time allocated to leadership development and political education on the root causes of the problems we face.

- Candidates often lack long-term political formation and frequently enter the electoral arena after shorter periods of organizing. This results in both fewer organizers in communities and a lack of cadre in office who can skillfully navigate the terrain. As revolutionaries, we need to think carefully about our practice when it comes to the political formation of candidates who we are running for office.

- Revolutionaries must go into the electoral arena with a clear theory and understanding of the state. Many organizers I spoke with reported no space to hash out a theory of the state: can we “take it over” or can it fundamentally not be reformed?.

- When our people get elected, they are confronted with the reality that they now have “co-workers” who they need to cooperate with on some level in order to “get things done”. Even if they are not captured by corporate interests, once people are embedded in the existing apparatus of the state, the people who surround them become their new normal. There is an inherent contradiction between getting into office as a disruptor and staying in office, which requires forming relationships with other officials, and inevitably, identifying with them.

- By and large, big elections are controlled by data-driven technocratic consultants that turn the process of elections into a science where people are numbers. These elections deal with us in much the same way as corporations do – collecting data on voters in order to parse out people’s likes, identities and interests in order to get them to “buy” a certain candidate. Clearly this type of process is transactional and not at all concerned with the human development of the people engaged in the work or being targeted as voters. Some people I spoke with have resorted to running their own campaigns completely independent of the consultants or the party apparatus.

- Vast amounts of money are spent by the ruling class on elections to mobilize us to go out and get them the result that they want, meaning that elections become another site where the working class jumps at the chance to get funding and ends up in a space of reaction to ruling class interests.

- It’s easy to de-mobilize once your friends are in office: you go from protesting to just being able to call them up.

- Economics trumps politics. There are serious limitations to what people can do once they are elected, as we continue to live in a dictatorship of the rich where every facet of life revolves around the protection of private profit at the expense of life and the planet.

- And finally, people who are most attracted to electoral work are not necessarily emerging out of the leading social force. Some of the most politically active people are those who, based on their own lived experience, believe in the basic goodness of the U.S. state, that the state can simply be reformed without a fundamental restructuring of power relationships between the working class and the ruling class, and that the main issue is disproportionality of impact, rather then very nature of the system.

Building the power and program of the poor

Having considered the experiences and lessons above, we can also deduce from the amount of resources and energy that a segment of the ruling class invests into voter suppression that there are real fissures and splits within the ruling class that we can take advantage of through engaging in the electoral arena.

But that is possible only as long as we’re clear, politically independent and building the leading social force through the process. There’s no doubt that organizations have done great work in building coalitions to get people elected, striving to keep those elected officials connected to their organizations, and organizing to inform their work and hold them accountable. But it is also true that building leaders through the electoral process requires going deeply against the grain, and that there are significant limitations to what anyone in office can accomplish in our current context.

Perhaps at the end of the day the critical question is whether or not we have enough revolutionary cadre to be able to engage in electoral campaigns in ways that actually help us move to higher stages of the revolutionary process. There is much more that can be said, examined and studied on this topic.

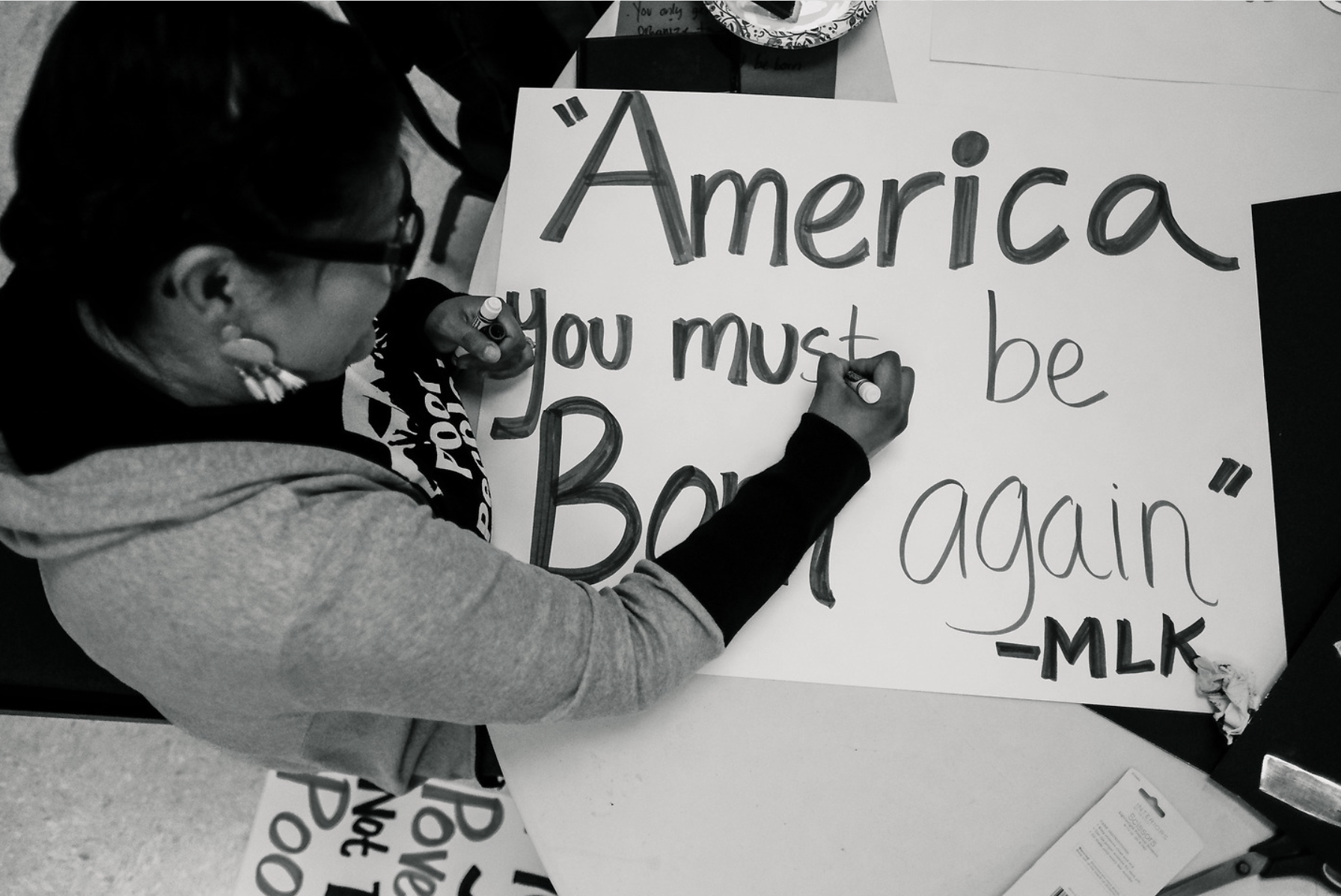

One exciting approach to political independence vis a vis the electoral arena that is not new, but has found renewed expression, is in the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival (PPC). Over the course of three years preceding the 2020 election, the PPC built up its power on the basis of organizing and mobilizing within states to develop a shared program and agenda of the 140 million poor and dispossessed people in this country today. The PPC committed to build leaders and power around that agenda and use that power and agenda to influence candidates, rather than endorse or run candidates themselves.

This approach has the advantage of creating more time and space to build leaders who are committed to a total program that represents the interests of the poor, rather than a cult of personality around a candidate. By emphasizing the program and the power, the Poor People’s Campaign understands that politics is fundamentally about millions of people coming into consciousness and moving in unison to change society, not about corporate parties or their figureheads.

Nijmie Zakkiyyah Dzurinko (she or they) is a working class Black, Indigenous and queer organizer, healer and strategist of over 20 years from Pennsylvania. She is co-founder of Put People First! PA, a working class, statewide, base building human rights organization waging a healthcare is a human right campaign. They are also a co-chair of the Pennsylvania Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival.

Thank you for this! Appreciate your emphasis on political independence based in class analysis, motion and issues: ‘bottom up’! Nicely done. Always up for sharing more thoughts on this as we, especially in the South, are experiencing multiple levels of assaults on the remnants of bourgeosie democracy: much of that aimed at ginning up a violent social base for fascism with its core of white supremacy. So much more to do, unpack, hold accountability and politically organize! Thank you again – will share this if ok.

Thanks so much Rita and thank you for informing this article!

[…] Original in English […]