By Willie Baptist and Kristin Colangelo

“Power never takes a step back except in the face of more power.”

– Malcolm X, Message to the Grassroots (1963)

“One unfortunate thing about [the slogan] Black Power is that it gives priority to race precisely at a time when the impact of automation and other forces have made the economic question fundamental for blacks and whites alike. In this context, a slogan “Power for Poor People’ would be much more appropriate than the slogan “Black Power.”

– Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, Where Do We Go From Here? (1967)

Organizing to build the unity of the poor and dispossessed should not be understood as just one among many items on the agenda. It has to be the agenda if we are going to give actual effect to our deepest aspirations for society. Building that unity is a question of power. Indeed, all of our studies and experiences have taught us that behind every demand and slogan lies the struggle for power. If this struggle is not solved then all of our best demands are reduced to empty moral appeals and all our catchiest slogans become toothless talk, no matter how loud or articulate, right or just, they are. This is a life and death question for the impoverished.

All power, including state power, originates from organization. The present fact is that the ruling class is organized, while the class of the poor and dispossessed is deliberately maintained as the most disunited and disorganized section of the population. In fact, the organization of the rich rests on our disorganization. This current situation presents the poor with a very dangerous problem of power. That is, in addition to being dispossessed or property-less (i.e. having no ownership in the means of production, retail, and financial services), the poor are the most powerless, with no means of securing their livelihood and lives.

Over the years, we’ve noticed a clear tendency everywhere to separate demands and moral outcries from the realities of the necessity of organizing. In other words, there has been a pronounced tendency to reduce strategy to morality. Certainly the poor and dispossessed need their own forms of morality that speak to the conditions and needs in their lives. In particular, they need their own ethical framework for what is just and unjust, right and wrong. This independent morality of the poor and dispossessed has an indispensable part to play in politically uplifting our own class values and consciousness and helping us to organize as a powerful and united class force.

Still, although ethics and morality are an indispensable part of political strategy, our strategy requires more. Actually defeating our class enemy requires more than having our own values of right and wrong. Our enemy doesn’t give a damn about our ethics nor the morality of our demands. They care only about their own bourgeois morality that justifies, aids, and abets their continuous exploitation and oppression of the poor and dispossessed.

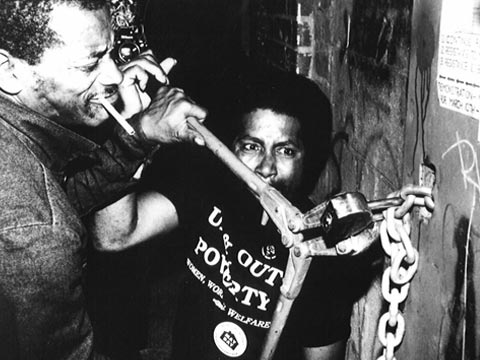

Pity is one expression of bourgeois morality. An important lesson drawn from the experiences of the National Union of the Homeless and the Kensington Welfare Rights Union is that pity is a political device utilized to dehumanize, isolate, and cruelly manipulate the different sections of the impoverished masses. Pity for the poor is no substitute for the necessity of power for the poor in their struggle to overcome the formidable political forces arrayed against them. This lesson is pointed out in Willie Baptist’s essay, “The Kensington Experience: the Poor Organizing the Poor”:

“The fight, as we see it, is not a fight for pity; it’s necessarily a fight for power…Unless we can generate the necessary kind of strength, through the organization and building of a broad and powerful movement, there’s nothing in the history of this country and of the world that suggests that we can rearrange the priorities of this nation. Every time, every instance that we can see in history where changes were indeed made, those changes were made on the basis of… organization that lead to relationships of power, and not relationships… of pity.”

Every front of struggle we take up, everything we do and say as revolutionaries and political strategists of the class of the poor and propertyless, must be translated into the question of organization. For one, our strategy must be pursued through the tactical work of agitation around the intensifying issues and crises of water, food, housing, healthcare, pollution, militarism, the mass incarceration of the poor, racial and police repressions, etc. Today, this approach cannot be limited to simply “community organizing” or narrow trade union organizing. It must involve mass political class organizing. And central to this type of organizing is ongoing political education.

Education becomes political when its primary purpose is to clarify for the struggles of the poor and dispossessed the economic and political forces that they are up against; to make clear that they are everywhere going up against the all powerful and globalized U.S. state apparatus, which is the capitalists organized as the ruling class. This class and its control of the U.S. state is the greatest purveyor of violence in world history. It is a ruling class that holds onto and deploys state power to protect and maintain the existing economic class structure that is benefiting them and killing us.

The main and immediate demands for human rights, or “entitlements” to the basic economic, social, and cultural necessities of life, are non-negotiable. This is true in these times when the false claim of scarcity of funds and resources is but a hollow sound. This is especially true due to the fact that the world has reached a period of unheard of productivity where poverty exists in the midst of plenty; abandonment resides right next to abundance. Due to the fundamental political nature of demands for human rights, our efforts can not be directed at just individual electoral officeholders or particular employer or governmental agency, or whoever. The demands for immediate human relief and for the fundamental human right to not be poor must be confronted by the state in all its various agencies, including ICE, the police and military forces, the judicial and prison system, and the intelligence services.

The political power of the ruling class is reinforced by the organization of force and violence of the U.S. state apparatus. It is no accident that this power rests on the disunity and disorganization of poor and dispossessed masses. To understand why, we must maintain a historical perspective. To start, we must remember the historic reshaping of the material and mental terrains of the United States with the defeat of Reconstruction after the U.S. Civil War. This defeat saw the emergence in power of Wall Street and the establishment of the “Solid South” as the most reactionary and racist region of the United States. The white supremacist “Solid South” has since constituted an all-white, all-classes (rich and poor) unity that serves as the main regional bastion of the disunity of the poor and dispossessed along color lines in the country.

W. E. B. Dubois’s Black Reconstruction describes the emergence and establishment of the political formula for how the U.S. has been ruled since the defeat of Reconstruction. That formula has long been formulated as “the South controls the nation, while Wall Street controls the South.” In other words, this political formula has long been predicated on the fact that those at the bottom of the economic ladder, the poor and dispossessed, remain the most disunited, most racially segregated, most voter suppressed, and most disorganized section of the U.S. population. And this managed fact has long been the pivot of Wall Street and of its political and ideological strategy and tactics. Dr. King, in his famous 1967 Beyond Vietnam War speech, called this “the cruel manipulation of the poor” in domestic and foreign policy.

Important lessons from history can be learned about how this racial formula of political control found expression decades later in the all-white “law and order” (or “White Power”) and “Black Power” responses to the 1960’s ghetto uprisings. They were both manipulated in different ways by the political strategists of the ruling class. In opposition to this strategic and shrewd manipulation were such politically threatening efforts as Dr. King’s launching of the Poor People’s Campaign and that of the original Rainbow Coalition in Chicago, led by Fred Hampton and Bobby Lee of the Black Panthers. These efforts were attempting to build the unity and organization of the poor and dispossessed across especially color-lines. Consequently, such efforts were subjected to destruction by outright murder, jailing, and co-optation.

All levels of the U.S. government participated in the execution of Dr. King, later revealed in the 1999 MLK Assassination Trial in Memphis, Tennessee. All revolutionaries should study the transcript of that historic trial. The main lesson that the ruling class wants understood from that trial and the murder of Fred Hampton is that “you do not unite the bottom!” Dr. King’s brave actions and strategic foresightedness were understood as threats to this political bottom line of Wall Street. The threat he posed was summed up in a clear and prescient statement he made going into the launching of the 1967 Poor People’s Campaign:

“The dispossessed of this nation — the poor, both white and Negro — live in a cruelly unjust society. They must organize a revolution against the injustice, not against the lives of the persons who are their fellow citizens, but against the structures through which the society is refusing to take means which have been called for, and which are at hand, to lift the load of poverty. There are millions of poor people in this country who have very little, or even nothing, to lose. If they can be helped to take action together, they will do so with a freedom and a power that will be a new and unsettling force in our complacent national life…”

Uniting the poor and dispossessed across color lines and all other lines of division is the number one political threat to the economic status quo of the United States. It is such a threat because of the present socioeconomic class position of the poor and homeless; that is, they occupy the bottom economic layer of society and embody, at once, all the major ills and pains of society. The poor are doubly such a threat because their unity and organization around economic and social issues would provide a powerful rallying point for winning a critical mass of the middle-income strata of the country.

The majority of the middle-income strata, like the poor and low-income, are dispossessed and propertyless and, because of the changing nature of the economy, are increasingly being thrown into poverty and precarity. The middle-income strata and their families in the U.S. have historically served as the social base of state power held by the ruling capitalist class. They have served as the officer corps of the state’s military, police, intelligence services, and governmental bureaucracies, as well as in the commanding heights of the economy. Weakening this social base of the U.S. state apparatus opens the door to actually building a movement to end poverty.

This is undoubtedly what FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover had in mind when he labeled the Black Panther Party as “the number one internal threat” to U.S. national security in 1968. They were such a threat because they had begun to actually unite and inspire a growing class unity and organization of the poor and dispossessed. This political threat reached its most dangerous point for the ruling class when, under the leadership of the Black Panthers in Chicago, the original “Rainbow Coalition” was formed. This coalition of “the bottom” included not only poor Latinx organizers with the Young Lords, but also poor whites of the Young Patriots in Uptown Chicago.

The Black Panthers were clear that getting the poor and dispossessed to unite and take action together can only work when their efforts are held together by a clear, committed, connected, and competent fighting group of leaders who are at the same time both teachers and organizers. This point can’t be overemphasized. Central to the task of building a transformative movement of the poor is political education, in which newly emerging leaders “learn as they lead, teach as they fight, talk as they walk.” Explaining this indispensable aspect of the poor organizing the poor, Rev. Dr. Liz Theoharis writes in chapter 11 of Pedagogy of the Poor:

“In our work of building a social movement to end poverty, we have found that education is central. If we are serious about ending poverty, we don’t have to merely do more actions, we have to do smarter actions…To outfight the forces arrayed against us, we must outsmart them. Nowhere in world history can anyone find where a dumb force rose up and defeated a smart force. Therefore, it is vitally important for anyone interested in ending poverty to develop an engaged intelligence that will outsmart, not only out-organize, the current conditions that cause poverty and misery.“

The role of political education at the center of political organizing is to equip our leaders and organizers to be able to, as Dr. King once instructed, make an accurate diagnosis of the disease so as to apply an accurate prescription for the cure. Any effective approach to social change, organizing, and leadership development has to be based on an accurate assessment of the situation and an accurate analysis of the problem to be solved. When you make an assessment or a certain diagnosis of the disease to be cured, you’re going to have a particular prescription and a particular approach to the solution. In our work, we like to say that when you are sizing up a situation you might not know right away whether you’re dealing with a teddy bear or a grizzly bear. Knowing which you’re dealing with has life-and-death consequences.

So an accurate estimate of the situation has to be where we begin. Today, this neccesarily involves a tremendous amount of ongoing and coordinated intellectual work to effectively and efficiently guide the practical work of the poor organizing the poor.